Gurukula (गुरुकुलम्)

Gurukula (Samskrit : गुरुकुलम्) is the place of learning for students after undergoing Upanayana, under the supervision of a learned Guru. Gurukula system was an important unique feature of ancient education system but has now lost its glory owing to the present day educational system brought in by the various rulers of India over the few centuries. Although modern education system has a few advantages, many good features of the ancient education system have been totally eliminated leaving a cultural gap.

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

The Gurukula system which necessitated the stay of the student away from his home at the house of a teacher or in a boarding house of an established institution, was one of the most important features of Bharatiya Shikshana vidhana. Sharira (शरीरम् । Body), Manas (मनः । mind), Buddhi (बुद्धिः । intellect) and Atma (आत्मा । spirit) constitute a human being; the aims and ideals of Prachina Bharatiya Vidya Vidhana or Ancient Indian Education system were to promote their simultaneous and harmonious development.[1] In this article we discuss the Gurukula set up, the aims of such educational system, the persons involved, and the syllabus taught under their guidance.

विद्या ॥ Vidya or Education

Vidya (विद्या) regarded as general education in common parlance, is the source of that Jnana which leads its recipients to successfully overcome difficulties and problems of life and in the Vedanta terms it is that knowledge which leads one on the path of Moksha. It was therefore insisted to be thorough, efficient with the goal of training experts in different branches. Since printing and paper were unknown, libraries and books did not exist, training essentially focused on developing memory that would stand good stead throughout the student's life.[1]

ऋणत्रयसिध्दान्तः ॥ Rna Siddhanta

Vedic age references speak about the Three Debts (ऋणत्रयम्) which served the purpose of instilling moral values in the younger generation to accept and maintain the best traditions of thought and action of the past generations. According to this siddhanta the moment an individual is born in this world, he incurs three debts, which he can discharge only by performing certain duties.

- देवऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Devatas is relieved by learning how to perform yajnas and by regularly offering them. Thus religious traditions are preserved.

- ऋषिऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Rshis of the bygone ages can be discharged by studying their works and continuing their literary and professional traditions. Thus the literary traditions are preserved.

- पितृऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Pitrs or ancestors can be repaid by getting married to raise progeny and impart education to them. Thus the family tradition is preserved.

Taittriya Samhita mentions the three debts as follows.

जायमानो वै ब्राह्मणस्तृभिर्ऋणैर्ऋणवाञ्जीयते । यज्ञेन देवेभ्यो ब्रह्मचार्येण ऋषिभ्यः प्रजया पितृभ्यः ॥ (Tait. Samh)

jāyamāno vai brāhmaṇastr̥bhirr̥ṇairr̥ṇavāñjīyate । yajñena devebhyo brahmacāryeṇa r̥ṣibhyaḥ prajayā pitr̥bhyaḥ ॥

Steps were taken to see that the rising generation became an efficient torch bearer of the culture and traditions of the past. Body, mind, intellect and Atma constitute a human being; the aims and ideals of ancient system of education were thus to promote their simultaneous and harmonious development.

गुरुकुलव्यवस्था ॥ Gurukula System

Smrtis recommend that the student should begin to live under the supervision of his teacher after his Upanayana. Etymologically Antevasin (अन्तेवासिन्) is the word for the student, denotes one who stays near his teacher. Samavartana (समावर्तनम्), the word for convocation, means the occasion of returning home from the boarding or the teacher's house. Here we describe the different aspects of a Gurukula system of education.[1]

गुरुकुललक्ष्याणि ॥ Aims of Gurukula

Gurushishya Parampara was the heart of the dharmika system of education in ancient times. From ashramas in the forests to temples in the villages to purely educational cities such as Kashi and Kanchi, it was this Gurukula system that brought to us (in the present day) the great cultural heritage that we still have. Its aims were multidimensional and far-reaching. The colonial era rulers having plundered the nation, in an attempt to break down the Bharatiya samajika vidhana (social fabric) targeted the education system in the name of reforms and upliftment of the downtrodden. The Aims of Gurukula System were lofty and kept in view the holistic development (physical, mental and social) of the student.

Location of a Gurukula

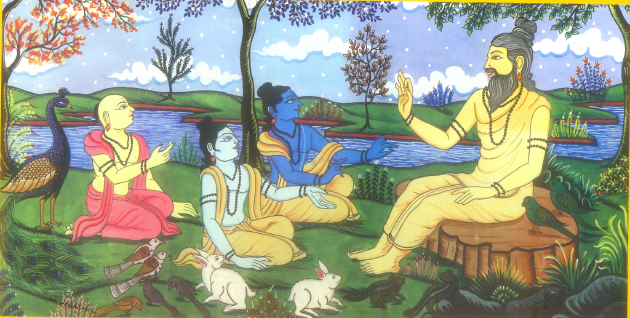

Shri Krishna and Balarama were sent to the Gurukula of Guru Sandipani is a well known example that students were actually being sent to reside with their preceptors. Now, there are various versions about the location of a Gurukula. In earlier times majority of teachers (Seers like Valmiki, Kanva, Sandipani) preferred the sylvan solitude of the forests to teach high level philosophies. Gradually as time passed, as supplies became scarce, Gurukulas came to be located near villages and towns chiefly because villagers around would provide their few and simple wants. Care was taken to locate the Gurukula in a secluded place, in a garden and ensured the holy setting.[1] The following are the different locations of Gurukulas each having specific advantages.

- Ashramas in a forest (Kanva and Valmiki)

- Outside but close to a village

- Centers of learning and education (Ujjaini, Varanasi, Kanchi, Thanjavur)

- Agraharas (अग्रहारम्), Gatikas (घटिका) and Tols (तोलः) are villages consisting only of Brahmana scholars.

गुरुः ॥ Guru or Preceptor

वित्तं बन्धुर्वयः कर्म विद्या भवति पञ्चमी । एतानि मान्यस्थानानि गरीयो यद्यदुत्तरम् । । २.१३६ । । (Manu. Smrt. 2.136)[2]

vittaṁ bandhurvayaḥ karma vidyā bhavati pañcamī । etāni mānyasthānāni garīyo yadyaduttaram । । 2.136 । ।

Possession of Wealth, Family (blood-relations), Age, Actions and Learning being the fifth are the Manyasthanas (मान्यस्थानानि । abodes of respect) with increasing weightage respectively. (i.e., Vidya is the highest abode of respect in comparison to Actions and so on).

Among the people of the four varnas, those having the above 5 manyasthanas are said to be the most respectful in the world (मानार्हः).[3][4]

Thus we see Gurus held an esteemed position in the society due to their Vidya. Gurukulas were headed by learned Gurus or teachers (आचार्याः) who were also householders. The famous Samavartana or convocation address to students in the Shikshavalli of Taittriya Upanishad, Anuvaka 11 extols the greatness of the Gurus in the life of a human starting with the Mother, then Father, followed by Guru and Atithi; all of them have to be revered as Devatas themselves.

मातृदेवो भव । पितृदेवो भव । आचार्यदेवो भव । अतिथिदेवो भव । mātr̥devo bhava । pitr̥devo bhava । ācāryadevo bhava । atithidevo bhava । (Tait. Upan. Shikshavalli 11.2)

Gurus such as Vasishta were associated with the members of the lineage of Ikshvaku and advised them long before Shri Rama was born. So was the case of many such Rshis and Maharshis. A Guru (गुरुः) is a person who takes charge of immature children and makes them worthy and useful citizens for the society, was naturally held in very high reverence. The preceptor naturally possessed several qualifications. He was expected to be a pious person, with high character, patient, impartial, inspiring and well grounded in his own branch of knowledge; he was to continue his reading throughout his life.[1]

It was the duty of the teacher to teach; all students possessed of the necessary calibre and qualifications were to be taught, without withholding knowledge irrespective of whether the student would be able to pay an honorarium or not. A Guru is the spiritual father of the child and was held as morally responsible for the drawbacks of his pupils. He was to provide food clothing and shelter to the student under his charge and help him get financial help from people of influence in the locality.

It is usually held that the profession of teaching was vested with the Brahmana community and they held a monopoly over the Vedic education. Dr. Altekar discusses extensively on this topic as to how we find that Kshatriya teachers of Vaidika and Vedanta subjects also existed down till the recent millenium and that Brahmanas were instrumental in furthering the knowledge in several non-vaidika subjects. Only in the later times did religious and literary studies came to be confined to the Brahmanas and professional and industrial training to non-Brahmanas. Examples of such exceptions include

- Pravahana Jaivali was the Kshatriya teacher who taught Brahmavidya to Shvetaketu a Brahmana. Asvapati and Janaka were other famous Kshatriya teachers.

- Satyakama was the son of a fallen woman but maintained Srauta fires and taught Brahmavidya to Upakosala a Brahmana.

- Maharshi Visvamitra, a Kshatriya is credited with the composition of the 3rd Mandala of Rigveda.

- Dronacharya being the best example of a Brahmana teaching the Pandavas and Kauravas about the art of warfare, Dhanurveda which was the skill of Kshatriyas.[1]

उपनयनसंस्कारः ॥ Upanayana Samskara

One of the unique Dharmas followed from time immemorial is the performance of Upanayana samskara for children entering the educational phase of life. Brahmanas, Kshatriyas and Vaishsyas are to perform Upanayana samskara after which the child is referred to as Dvija (द्विजः । twice born). It marks the beginning of the Brahmacharyashrama. The young mind is trained to perform many social as well as personal duties with specific attention to maintaining the fires, perform sandhyavandana and adhyayana (studies). Respectful behavior towards the Guru and serving him (sushsruta) are foremost duties of a Brahmachari.

अन्तेवासिन् ॥ Antevasin or Student

The student enrolled in the Gurukula is called as Antevasin (अन्तेवासिन्), a Shishya (शिष्यः), was to hold his teacher in deep reverence and honour him like the King, the Devatas and his Parents. A student is generally is said to be in the Brahmacharyashrama, the stage of gaining knowledge, with many personal and social duties. After completion of his studies, the Samavartana rite is performed, which includes a ritual of snana after which the student is called Snataka. A Naishtika Brahmachari is one chooses to live his entire life as a Brahmachari without getting into the Grhasthashrama.

Vidyarthi's qualities and thus his behavior must be in conformity with the rules and decorum of the Gurukula, whether he is rich or poor. Only students with the following qualities deserve to be taught according to Yajnavalkya Smrti

कृतज्ञाद्रोहिमेधावि शुचिकल्यानसूयकाः । अध्याप्या धर्मतः साधु शक्ताप्तज्ञानवित्तदाः । । १.२८ (Yajn. Smrt. 1.28)[5]

kr̥tajñādrohimedhāvi śucikalyānasūyakāḥ । adhyāpyā dharmataḥ sādhu śaktāptajñānavittadāḥ । । 1.28

Gratefulness (कृतज्ञः), Free from enmity (अद्रोहिः), Intelligent (मेधावि), Pure (शुचिः), free of mental and physical diseases, not in the habit of fault-finding, virtuous, strong and capable (of serving), family member, giver of knowledge (in return for knowledge), and giver of wealth (in return for knowledge).

The student was expected to do personal service to the teacher "like a son, supplaint, or slave". Mahabharata (1.25.11-12) give minute details of how service should be done to the Guru, including carrying his water for bath and cleaning his utensils, tending to cows, bringing samidhas and maintaining the sacred fires.

Gopatha Brahmana (1.2.1to8) explains that this Sushurta or service was very prevalent in the Vaidika age and is widely prevalent in later times also. It was a honour to do service to the Guru and it was extolled that no progress in knowledge was possible was possible without doing service in the teacher's house (Maha. Vana 36.52).

Students were always to follow the instructions of the Guru obediently, ought to salute his teacher, ought not to occupy a seat higher than the teacher, never wear a gaudier dress, refrain from reviling and backbiting.

Seeking others for daily food or Bhikshatana is one feature enjoined on the student as a religious duty. This vidhi occurs in many Grhya sutra texts and is prevalent since Vedic times. The story of Dhaumya and one of his students Upamanyu is a classic example of how begging for food and first offering it to the Guru has been duty of the student.[1]

Education of Girls

Admission, Syllabus and Examinations

In vedic times, a student was to directly enter a Gurukula after initiation by Upanayana, without having to write any entrance test nor does the Guru interview of the child. Admission of the child was a hassle free process, no boards of studies only the parents of the child chose the Guru under guidance they wanted the child. Prachina shikshana vidhana was not focused on examinations, diplomas and migration or transfer certificates. Ancients regarded knowledge as unlimited and no period that one could spend for its acquisition was regarded adequate to complete mastering a Veda, thus Vedas were अनन्ताः । Ananta or endless.

However, higher education required a testing procedure to prove that the candidate was fit for it. Tests were mostly verbal in nature and required the recitation of Vedas or subject matter from memory. The class size was not too large as the aim was to give personal attention to students. Paper and books, as well as tubelights and continuous lighting facilities were absent so homework or reading after hours was practically impossible. All the work has to be done under the guidance of the teacher or class monitor who was incharge of the younger students.

Chaturdasha Vidyastanas which included the Four Vedas and their Vedangas were the chief subjects and constituted the study syllabus during the earliest times. Specialized Para Vidya including Brahmavidya, Panchagni vidya etc of the olden days gradually got absorbed into Vedanta system, a broader heading covering all such specialized topics was a higher level course and required years of sadhana. Gradually as studying vedas required more understanding, the study of Shad Vedangas became important. It is to be noted that the subjects explaining the Vedas themselves gained more significance and subsequently were studied independent of the Vedas themselves.

The knowledge of alloys, metallurgy, geology, botany sciences, warfare, architecture, large scale constructions, all such topics developed over a period of time into professional subjects.

Daily Life of a Student

Here in the present context, the general life of a student of religious and literary education is dealt with. Ashramas and Gurukulas having different specialized courses and those where higher yajnas were conducted had different schedules. Most of the time of a Vedic studies student is spent in recollecting, recapitulation and recitation of the vedas to commit them to memory. However, even students of other shastras had to memorize their lessons in earlier days. A brief outline of a student's life is as follows

- Rise early in the morning before birds begin to stir i.e., at about 4.30 am.

- Attend morning functions, bath and offering of Sandhyavandana.

- Students get involved in samidadhana, offering of samidhas in the grhya fires.

- Revising old lessions by recitation and learning new lessons.

- Around mid-day students went for collection of their meals by Bhikshaatana. In some cases the teacher's family provided the meals.

- Resting period in the afternoon post-lunch for an hour.

- Resuming studies around 2.30 pm till evening.

- Collection of samidhas for yajnas and physical exercise.

- At sunset offering of evening Sandhyavandana and samidadhana.

- Dinner and retiring for the day.

अनध्ययनम् ॥ Anadhyayana or Holidays

A systematic list of holidays from studies goes back to very early times and include generally the Anadhyayana days of the month which were 6 days in a month - the two astami (eight day) and Chaturdashi (fourteenth day) tithis of the fortnight, the amavasya (new moon day) and purnima (full moon day) days (Manu Smrt. 4.113 and 114).

पौर्णमस्य्-अष्टका-अमावास्या-अग्न्युत्पात-भूमिकम्प-श्मशान-देशपति-श्रो त्रिय-एकतीर्थ-प्रयाणेष्व् अहोरात्रम् अनध्यायः ॥ (Baud. Dhar. Sutr. 1.11)[6]

Apart from these at times of robbery in a village, cattle lifting, natural calamities, during thunders and rainstorms, death of the Raja or a Brahmana of the village, arrival of guests and during village celebrations, vedic study is paused. Gradually in due course of time the number of holidays reduced due to the curriculum getting heavier. While abnormal weather conditions prevented loud recitation, silent reading of non-Vedic subjects was allowed. While Vedic study had to be paused, non-Vaidika subjects could be studied on Anadhyayana days.[1]

गुरुदक्षिणा ॥ Guru Dakshina

Gurudakshina or the teacher's honorarium became payable only at the end of education and it was not mandatory. Samavartana is the convocation, time when the student leaves the Gurukula with the permission of the Guru. It is at the Samavartana time that the gurudakshina has to be offered by the student to the Guru. Payment of fees as a condition for admission was never a stipulation in the sacred texts. No student could be refused admission even by a private teacher simply because he was too poor to pay any fees. Teaching was a sacred duty and Smrtis condemned payment of stipulated fees as a condition precedent to admission. Gurudakshina was however acceptable form of payment either in monetary and service forms; a poor student could pay for his education by doing service to the Guru which became more common in the post vedic age.

Voluntary gifts from the guardians or parents of the child was not prevented. Shri Krishna's paid gurudakshina to his teacher Sandipani in the form of bringing back his lost child. Similarly, Arjuna defeated Drupada Maharaja as a gurudakshina after his education, for Dronacharya his Guru. So gurudakshina never was just monetary, it was in various forms and also depended on what the Guru may what apart from gold or land.

Maintenance of Gurukula

The next question is how did Gurukulas thrive as the most successful model of education? In the earlier times the followers of different Vedas had formed their own literary organizations like the Parishads, Shakas and Charanas and emphasis on forming a literary educational institutions was not present; largely because Brahmanas followed the injunction of learning the Vedas and devoteing themselves to teaching as per their capacity. Each Brahmana was thus an educational institution by himself and was self sufficient. The requirements were simple havya and kavya for the rshis and the nearby forests provided the samidhas. (check for references and examples)

Since the early times the responsibility of providing for the Gurukulas vested with the Rajas and Maharajas. They were self sufficient and their simple essential needs were fulfilled by the villagers. Hence direct monetary requirements were more for the conduct of yajnas (which were also the responsibility of the Guru) where offering of danas required monetary support. The story of Vishvamitra seeking gold from Raja Harishchandra for conducting a yajna is one famous example.

In later years the Rajas and Maharajas made huge donations to the cause of developing educational centers. Agrahara institutions, Mathas, and temple colleges were all imparting free education to their students. When they received sufficient endowments, they would also arrange to provide free boarding, lodging, clothing and medicine to the students they admitted. Education in ancient India was free in much wider sense than in the modern times.

Modern Education System

Prior to 18th century with Muslim invasions, the ancient education system was declining slowly and gradually. The advent of the European interest in India led to scholarly attention and debate about India in the western society. Prominent amongst these were members of several Christian monastic orders, the most well known being the Jesuits, who were specialising in the fields of the sciences, customs, manners, philosophies and religions. There were some others with interests of a more political, historical or economic nature. Those connected to the Universities were particularly interested in politics, laws, philosophies and sciences, especially the Indian Astronomy. Adam Ferguson of University of Edinburgh, William Roberson, John Playfair were a few interested in collecting the complete information about India, its people (to the minute detail), the occupations, the resources, and the way of life of each of the communities that existed. Discussion and debates about India, its literacy spread far and wide. Prof. Maconochie also stated that the centre of most of this learning was Benares, where ‘all the sciences are still taught’ and where ‘very ancient works in astronomy are still extant.’29 Three approaches (seemingly different but in reality complementary to one another) began to operate in the British held areas of India regarding Indian knowledge, scholarship and centres of learning from about the 1770s.

The first resulted from growing British power and administrative requirements which (in addition to such undertakings that men like Adam Ferguson had recommended) also needed to provide a garb of legitimacy and a background of previous indigenous precedents (however farfetched) to the new concepts, laws and procedures which were being created by the British state. It is primarily this requirement which gave birth to British Indology.

The second approach was a product of the mind of the Edinburgh enlightenment (dating back to around 1750) which men like Maconochie represented. They had a fear, born out of historical experience, philosophical observation and reflection (the uprooting of entire civilizations in the Americas), that the conquest and defeat of a civilisation generally led not only to its disintegration, but the disappearance of precious knowledge associated with it. They advocated, therefore, the preparation of a written record of what existed, and what could be got from the learned in places like Varanasi.

The third approach was a projection of what was then being attempted in Great Britain itself: to bring people to an institutionalised, formal, law-abiding Christianity and, for that some literacy and teaching became essential. To achieve such a purpose in India, and to assist evangelical exhortation and propaganda for extending Christian ‘light’ and ‘knowledge’ to the people, preparation of the grammars of various Indian languages became urgent. The task according to William Wilberforce, called for ‘the circulation of the holy scriptures in the native languages’ with a view to the general diffusion of Christianity, so that the Indians ‘would, in short become Christians, if I may so express myself, without knowing it.’30

However, British interest was not centered on the people, their knowledge, or education, or the lack of it. Rather, their interest in ancient texts served their purpose: that of making the people conform to what was chosen for them from such texts and their new interpretations. Their other interest (till 1813, this was only amongst a section of the British) was in the christianisation of those who were considered ready for such conversions (or, in the British phraseology of the period, for receiving ‘the blessings of Christian light and moral improvements’). These conversions were also expected to serve a more political purpose, in as much as it was felt that it could establish some affinity of outlook and belief between the rulers and the ruled. A primary consideration in all British decisions from the very beginning, continued to be the aim of maximising the revenue receipts of Government and of discovering any possible new source which had remained exempt from paying any revenue to Government.

Thus control of education system moved from the Academician to the Government.

It is important to emphasize that indigenous education was carried out through pathshalas, madrassahs and gurukulas. Education in these traditional institutions—which were actually kept alive by revenue contributions by the community including illiterate peasants—was called shiksha (and included the ideas of prajna, shil and samadhi). These institutions were, in fact, the watering holes of the culture of traditional communities. Therefore, the term ‘school’ is a weak translation of the roles these institutions really played in Indian society. The most well-known and controversial point which emerged from the educational surveys lies in an observation made by William Adam. In his first report, he observed that there exist about 1,00,000 village schools in Bengal and Bihar around the 1830s.32 Thomas Munro, had observed that ‘every village had a school.’33 G.L. Prendergast noted ‘that there is hardly a village, great or small, throughout our territories, in which there is not at least one school, and in larger villages more.’34

Observations made by Dr G.W. Leitner in 1882 show that the spread of education in the Punjab around 1850 was of a similar extent. The conditions under which teaching took place in the Indian schools were less dingy and more natural;37 and, it was observed, the teachers in the Indian schools were generally more dedicated and sober than in the English versions. The only aspect, and certainly a very important one, where Indian institutional education seems to have lagged behind was with regard to the education of girls. The data reveals the background of the teachers and the taught. It presents a picture which is in sharp contrast to the various scholarly pronounce- ments of the past 100 years or more, in which it had been assumed that education of any sort in India, till very recent decades, was mostly limited to the twice-born38 amongst the Hindoos, and amongst the Muslims to those from the ruling elite. The actual situation which is revealed was different, if not quite contrary, for at least amongst the Hindoos, in the districts of the Madras Presidency (and dramatically so in the Tamil- speaking areas) as well as the two districts of Bihar. It was the groups termed Soodras, and the castes considered below them39 who predominated in the thousands of the then still-existing schools in practically each of these areas. The last issue concerns the conditions and arrangements which alone could have made such a vast system of education feasible: the sophisticated operative fiscal arrangements of the pre-British Indian polity. Through these fiscal measures, substantial proportions of revenue had long been assigned for the performance of a multiplicity of public purposes. These seem to have stayed more or less intact through all the previous political turmoils and made such education possible. The collapse of this arrangement through a total centralisation of revenue, as well as politics led to decay in the economy, social life, education, etc.

The collector of Cuddapah stated:

Although there are no schools or colleges supported by public contribution, I ought not to omit that amongst Brahmins, instruction is in many places gratuitously afforded and the poorer class obtain all their education in this way. At the age of from 10 to 16 years, if he has not the means of obtaining instruction otherwise, a young Brahmin leaves his home, and proceeds to the residence of a man of his own caste who is willing to afford instruction without recompense to all those resorting to him for the purpose. They do not, however, derive subsistence from him for as he is generally poor himself, his means could not of course give support to others, and even if he has the means his giving food and clothing to his pupils would attract so many as to defeat that object itself which is professed. The Board would naturally enquire how these children who are so destitute as not to be able to procure instruction in their own villages, could subsist in those to which they are strangers, and to which they travel from 10 to 100 miles, with no intention of returning for several years. They are supported entirely by charity, daily repeated, not received from the instructor for the reasons above mentioned, but from the inhabitants of the villages generally. They receive some portion of alms daily at the door of every Brahmin in the village, and this is conceded to them with a cheerfulness which considering the object in view must be esteemed as a most honourable trait in the native character, and its unobtrusiveness ought to enhance the value of it. We are undoubtedly indebted to this benevolent custom for the general spread of education amongst a class of persons whose poverty would otherwise be an insurmountable obstacle to advancement in knowledge, and it will be easily inferred that it requires only the liberal and fostering care of Government to bring it to perfection.48 The collector of Guntoor was equally descriptive and observed that though there seemed to be ‘no colleges for teaching theology, law, astronomy, etc. in the district’ which are endowed by the state yet, These sciences are privately taught to some scholars or disciples generally by the Brahmins learned in them, without payment of any fee, or reward, and that they, the Brahmins who teach are generally maintained by means of maunium land which have been granted to their ancestors by the ancient Zamindars of the Zillah, and by the former Government on different accounts, but there appears no instance in which native Governments have granted allowances in money and land merely for the maintenance of the teachers for giving instruction in the above sciences. Should people be desirous of studying deeper in theology, etc. than is taught in these parts, they travel to Benares, Navadweepum,49 etc. where they remain for years to take instruction under the learned pundits of those places.50

Four Stages of School Instruction

Adam divided the period spent in elementary schools into four stages. According to him these were: the first stage, seldom exceeding ten days, during which the young scholar was taught ‘to form the letters of the alphabet on the ground with a small stick or slip of bamboo’, or on a sandboard. The second stage, extending from two and a half to four years, was ‘distinguished by the use of the palm leaf as the material on which writing is performed’, and the scholar was ‘taught to write and read’, and commit ‘to memory the Cowrie Table, the Numeration Table as far as 100, the Katha Table (a land measure Table), and the Ser Table’, etc. The third stage extended ‘from two to three years, which are employed in writing on the plantain-leaf.’ Addition, subtraction, and other arithmetical rules were additionally taught during this period. In the fourth, and last stage, of up to two years, writing was done on paper. The scholar was expected to be able to read the Ramayana, Mansa Mangal, etc., at home, as well as be qualified in accounts, and the writing of letters, petitions, etc.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Altekar, A. S. (1944) Education in Ancient India. Benares : Nand Kishore and Bros.,

- ↑ Manusmriti (Adhyaya 2)

- ↑ Pt. Girija Prasad Dvivedi (1917) The Manusmriti or Manavadharmashastra (Hindi Translation) Lucknow: Nawal Kishore Press (Adhyaya 2 Sloka 136)

- ↑ Mm. Ganganath Jha (1920 - 1939) Manusmrti with the Manubhashya of Medathithi, English Translation. Volume 3, Part 1 Discourses 1 and 2. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass

- ↑ Yajnavalkya Smrti (Acharadhyaya Brahmachari Prakarana)

- ↑ Baudhyayana Dharmasutras