Gurukula (गुरुकुलम्)

Gurukula (Samskrit : गुरुकुलम्) is the place of learning for students after undergoing Upanayana, under the supervision of a learned Guru. Gurukula system was an important unique feature of ancient education system but has now lost its glory owing to the present day educational system brought in by the various rulers of India over the few centuries. Although modern education system has a few advantages, many good features of the ancient education system have been totally eliminated leaving a cultural gap.

Vidya (विद्या) regarded as general education in common parlance, is the source of that Jnana which leads its recipients to successfully overcome difficulties and problems of life and in the Vedanta terms it is that knowledge which leads one on the path of Moksha. It was therefore insisted to be thorough, efficient with the goal of training experts in different branches. Since printing and paper were unknown, libraries and books did not exist, training essentially focused on developing memory that would stand good stead throughout the student's life.[1]

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

The Gurukula system which necessitated the stay of the student away from his home at the house of a teacher or in a boarding house of an established institution, was one of the most important features of Bharatiya Shikshana vidhana. Sharira (Body), Manas (mind), Buddhi (intellect) and Atma (spirit) constitute a human being; the aims and ideals of Prachina Bharatiya Vidya Vidhana or Ancient Indian Education system were to promote their simultaneous and harmonious development.[1] In this article we discuss the Gurukula set up, the aims of such educational system, the persons involved, and the syllabus taught under their guidance.

Gurukula System

Smrtis recommend that the student should begin to live under the supervision of his teacher after his Upanayana. Etymologically Antevasin is the word for the student, denotes one who stays near his teacher and Samavartana, the word for convocation, means the occasion of returning home from the boarding or the teacher's house. Here we describe the different aspects of a Gurukula.[1]

Location of a Gurukula

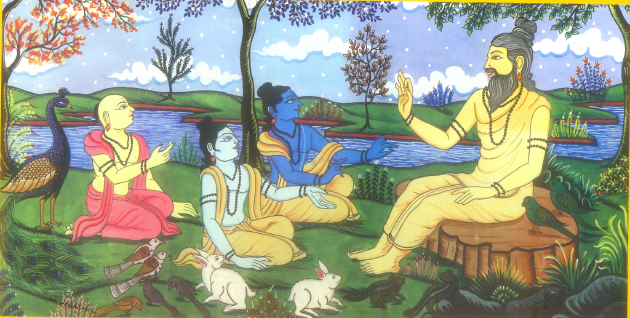

Shri Krishna and Balarama were sent to the Gurukula of Guru Sandipani is a well known example that students were actually being sent to reside with their preceptors. Now, there are various versions about the location of a Gurukula. In earlier times majority of teachers (Seers like Valmiki, Kanva, Sandipani) preferred the sylvan solitude of the forests to teach high level philosophies. Gradually as time passed, as supplies became scarce, Gurukulas came to be located near villages and towns chiefly because villagers around would provide their few and simple wants. Care was taken to locate the Gurukula in a secluded place, in a garden and ensured the holy setting.[1] The following are the different locations of Gurukulas each having specific advantages.

- Ashramas in a forest (Kanva and Valmiki)

- Outside but close to a village

- Centers of learning and education (Ujjaini, Varanasi, Kanchi, Thanjavur)

- Agraharas, Gatikas and Tols (villages consisting only of Brahmana scholars)

Guru or Preceptor

Gurukulas were headed by learned Gurus or teachers who were also householders. Their held an esteemed position in the society and Atharvaveda clearly extols the greatness of the mother, the father and the Guru. 11.5.3

गृणाति उपदिशति तात्त्विकमर्थम् इति गुरुः -- शिवसूत्रविमर्शिनी

Gurus such as Vasishta were associated with the members of the lineage of Ikshvaku and advised them long before Shri Rama was born. So was the case of many such Rshis and Maharshis. Guru is a person who takes charge of immature children and makes them worthy and useful citizens in society, was naturally held in very high reverence. The preceptor naturally possessed several qualifications. He was expected to be a pious person, with high character, patient, impartial, inspiring and well grounded in his own branch of knowledge; he was to continue his reading throughout his life.[1]

It was the duty of the teacher to teach; all students possessed of the necessary calibre and qualifications were to be taught, without withholding knowledge irrespective of whether the student would be able to pay an honorarium or not. A Guru is the spiritual father of the child and was held as morally responsible for the drawbacks of his pupils. He was to provide food clothing and shelter to the student under his charge and help him get financial help from people of influence in the locality.

It is usually held that the profession of teaching was vested with the Brahmana community and they held a monopoly over the Vedic education. Dr. Altekar discusses extensively on this topic as to how we find that Kshatriya teachers of Vaidika and Vedanta subjects existed down till the recent millenium and that they were instrumental in furthering the knowledge in several non-vaidika subjects. Only in the later times did religious and literary studies came to be confined to the Brahmanas and professional and industrial training to non-Brahmanas. Examples of exceptions include

- Pravahana Jaivali was the Kshatriya teacher who taught Brahmavidya to Shvetaketu a Brahmana. Asvapati and Janaka were other famous Kshatriya teachers.

- Satyakama was the son of a fallen woman but maintained Srauta fires and taught Upakosala a Brahmana.

- Maharshi Visvamitra, a Kshatriya is credited with the composition of the 3rd Mandala of Rigveda.

Brahmanas also pursued non-vaidika professions, Dronacharya being the best example of a Brahmana teaching the Pandavas and Kauravas about the art of warfare, Dhanurveda.[1]

Antevasin or Student

The student called as Antevasin, was to hold his teacher in deep reverence and honour him like the King, devatas and his parents according to the Manudharmashastra (2.200). His outward behaviour must be in conformity with the rules and decorum of the Gurukula, whether he is rich or poor. The student was expected to do personal service to the teacher "like a son, supplaint, or slave". Mahabharata (1.25.11-12) give minute details of how service should be done to the Guru, including carrying his water for bath and cleaning his utensils, tending to cows, bringing samidhas and maintaining the sacred fires. Gopatha Brahmana (1.2.1to8) explains that this Sushurta or service was very prevalent in the Vaidika age and is widely prevalent in later times also. It was a honour to do service to the Guru and it was extolled that no progress in knowledge was possible was possible without doing service in the teacher's house (Maha. Vana 36.52).

Students were always to follow the instructions of the Guru obediently, ought to salute his teacher, ought not to occupy a seat higher than the teacher, never wear a gaudier dress, refrain from reviling and backbiting.

Seeking others for daily food or Bhikshatana is one feature enjoined on the student as a religious duty. This vidhi occurs in many Grhya sutra texts and is prevalent since Vedic times. The story of Dhaumya and one of his students Upamanyu is a classic example of how begging for food and first offering it to the Guru has been duty of the student.[1]

Admission, Syllabus and Examinations

In vedic times, a student was to enter a Gurukula after initiation by Upanayana. Prachina shikshana vidhana was not focused on examinations, diplomas and migration or transfer certificates. However, higher education required a testing procedure to prove that the candidate was fit for it. Tests were mostly verbal in nature and required the recitation of Vedas or subject matter from memory. The class size was not too large as the aim was to give personal attention to students. Paper and books, as well as tubelights and continuous lighting facilities were absent so homework or reading after hours was practically impossible. All the work has to be done under the guidance of the teacher or class monitor who was incharge of the younger students.

Chaturdasha Vidyastanas which included the Vedas and their Vedangas were the chief subjects and constituted the study syllabus during the earliest times. Specialized Para Vidya including Brahmavidya, Panchagni vidya etc of the olden days gradually got absorbed into Vedanta system, a broader heading covering all such specialized topics was a higher level course and required years of sadhana. Gradually as studying vedas required more understanding, the study of Shad Vedangas became important. It is to be noted that the subjects explaining the Vedas themselves gained more significance and subsequently were studied independent of the Vedas themselves.

The knowledge of alloys, metallurgy, geology, botany sciences, warfare, architecture, large scale constructions, all such topics developed over a period of time into professional subjects.

Daily Life of a Student

Here the general life of a student of religious and literary education is dealt with. Ashramas and Gurukulas having different specialized courses and those where higher yajnas were conducted had different schedules. Brief outline is as follows

- Rise early in the morning before birds begin to stir i.e., at about 4.30 am.

- Attend morning functions, bath and offering of Sandhyavandana.

- Students get involved in samidadhana, offering of samidhas in the grhya fires.

- Revising old lessions by recitation and learning new lessons.

- Around mid-day students went for collection of their meals by Bhikshaatana. In some cases the teacher's family provided the meals.

- Resting period in the afternoon post-lunch for an hour.

- Resuming studies around 2.30 pm till evening.

- Collection of samidhas for yajnas and physical exercise.

- At sunset offering of evening Sandhyavandana and samidadhana.

- Dinner and retiring for the day.

Guru Dakshina

Gurudakshina or the teacher's honorarium became payable only at the end of education. Samavartana is the convocation, time when the student leaves the Gurukula with the permission of the Guru. It is at the Samavartana time that the gurudakshina has to be offered by the student to the Guru. Payment of fees as a condition for admission was never a stipulation in the sacred texts. No student could be refused admission even by a private teacher simply because he was too poor to pay any fees. Teaching was a sacred duty and Smrtis condemned payment of stipulated fees as a condition precedent to admission. Gurudakshina was however acceptable form of payment either in monetary and service forms; a poor student could pay for his education by doing service to the Guru which became more common in the post vedic age.

Voluntary gifts from the guardians or parents of the child was not prevented. Shri Krishna's paid gurudakshina to his teacher Sandipani in the form of bringing back his lost child. Similarly, Arjuna defeated Drupada Maharaja as a gurudakshina after his education, for Dronacharya his Guru. So gurudakshina never was just monetary, it was in various forms and also depended on what the Guru may what apart from gold or land.

Maintenance of Gurukula

The next question is how did Gurukulas thrive as the most successful model of education? In the earlier times the followers of different Vedas had formed their own literary organizations like the Parishads, Shakas and Charanas and emphasis on forming a literary educational institutions was not present; largely because Brahmanas followed the injunction of learning the Vedas and devoteing themselves to teaching as per their capacity. Each Brahmana was thus an educational institution by himself and was self sufficient. The requirements were simple havya and kavya for the rshis and the nearby forests provided the samidhas. (check for references and examples)

Since the early times the responsibility of providing for the Gurukulas vested with the Rajas and Maharajas. They were self sufficient and their simple essential needs were fulfilled by the villagers. Hence direct monetary requirements were more for the conduct of yajnas (which were also the responsibility of the Guru) where offering of danas required monetary support. The story of Vishvamitra seeking gold from Raja Harishchandra for conducting a yajna is one famous example.

In later years the Rajas and Maharajas made huge donations to the cause of developing educational centers. Agrahara institutions, Mathas, and temple colleges were all imparting free education to their students. When they received sufficient endowments, they would also arrange to provide free boarding, lodging, clothing and medicine to the students they admitted. Education in ancient India was free in much wider sense than in the modern times.

Aims of Gurukula System

The Gurukula system was the mainstream education system till as recent as the first millenium which necessitated the stay of a student away from his home at the house or ashrama of Guru (teacher) who imparted valuable life lessons to the student. The direct aim of all education, literary or professional, was to make the student fit to deal with the problems in life, train him to develop those qualities that would make him a beneficial member of the society.

Imparting Dharmika Principles

Life in ancient Bharat was rooted in Dharma and associated activities. Activities or jivana vidhana involved being in constant communion with the Self and thus many preceptors, the rshis lived simple lives. The procedures of yajnas performed for the welfare of all beings in the world, vratas, nityakarmas (agnihotra, prayer to Surya etc) - all were to inculcate piousness and compassion in the young student, the bearer of the future generations. He is trained to control his senses and the rigorous spiritual background imbibed is expected to restrain the student from temptations of life. The setting was the ashram, the very atmosphere impresses upon him that through the body (a product of nature) the higher spiritual realms are to be achieved by his inner Self (along with buddhi and manas are to be directed towards Paramatman). To achieve this the Guru imparts those laws which govern the conduct thereby moulding his character for life.[1]

Limitations on Spiritual Practices

Although the gurukula system provided the dharmika and paramatmika jnana, the aim was not to induce the student immediately into a path for search of Brahman and turn him into a sanyasi. It is well known that maharshis had huge following of students involved in Vedic studies yet only a miniscule number of them pursued the spiritual journey (remaining as brahmacharis) while vast majority of them became grhasthas and spread the yajnika practices in the society. Thus role of Gurus was two fold - create new preceptors who spread the dharmika procedures in society and guide those students on the spiritual quest.

Character Building

Although Vedas and spiritual quest was regarded highly, maharshis, the educationalists, unhesitatingly declared that a person of good character with minimal knowledge of the Vedas is to be preferred to a scholar, who though well versed in the Vedas, led an impure life of lowly thoughts and habits. Importance of character has been stressed in many ancient texts

सावित्रीमात्रसारोऽपि वरं विप्रः सुयन्त्रितः । नायन्त्रितस्त्रिवेदोऽपि सर्वाशी सर्वविक्रयी । । २.११८ । । sāvitrīmātrasāro'pi varaṁ vipraḥ suyantritaḥ । nāyantritastrivedo'pi sarvāśī sarvavikrayī । । 2.118 । । (Manu. Smri. 2.118)[2]

धर्म हि यो वर्धयते स पण्डितः । dharma hi yo vardhayate sa paṇḍitaḥ । (Maha. Shan. Parv. 12.321.78)

He alone is learned (jnani) who contributes to growth of dharma. Maharshis were well aware that power without virtue and intellect without moral and spiritual disciplining led to disastrous consequences, hence emphasis was on learning along with building character.

The tree of education ought to flower in wisdom as well as in virtue, in knowledge as well as in manners.[1]

Gurukulas had the conducive methods to shape a student's character which included

- right natural surroundings

- direct instructions of vidhis (injunctions)

- direct and personal supervision by teachers (both on moral and intellectual behaviour)

- performing activities and nityakarmas (showed students the strict narrow path of duty)

- powerful reinforcement through examples of great personalities

Student Discipline

There is a misplaced impression that education system in ancient India suppressed personality development by imposing a uniform course of education enforcing it with an iron discipline (Page 12 of [1]). Although theoretically practice of hereditary profession was advocated freedom to enterprising individuals was never restricted. Restrictions on the whole Brahmana community to devote twelve years to the task of memorizing the Vedic tests was also not compelled, only a section of them dedicated themselves while the rest of the community learnt those sections of veda mantras that were to be used on the daily basis and were allowed to choose subjects of their choice such as tarka, nyaya, vedanta and other shastras. Kshatriyas and Vaishyas never took seriously to the Vedic learning and trained in the requisite shastras like the Brahmanas. It is wrong to conclude from passages (such as Manu. Smrt. 2.168 and 3.1) that Manusmrti emphasizes that the vedic study was compelled for Brahmanas[1]

योऽनधीत्य द्विजो वेदं अन्यत्र कुरुते श्रमम् । स जीवन्नेव शूद्रत्वं आशु गच्छति सान्वयः । । २.१६८ (Manu. Smrt. 2.168)

A dvija who does not study the vedas and takes up efforts to study other shastras, such a person, while living, attains the state of a shudra along with his descendents.[3](Page 456 of Reference [4]). Here the context of the passages have to be considered while arriving at a conclusion.

Students were taught to be self disciplined and instilled with value systems from a very young age based on their personal capacity.

Development of Personality

The development of personality was one of the important aims of the education system. He was instilled with self-confidence, self-respect by inculcating the virtue of self-restraint and by fostering the powers of discrimination and judgement. The student was always reminded to be the custodian and torch bearer of the culture of the race and its welfare depended upon his proper conduct of his duties. Supporting a poor student was the sacred duty of the society. Students were given utmost importance in society for they were the future custodians of the society.

Influence of Self-confidence

The Upanayana ritual used to foster self-confidence by pointing out that divine powers would cooperate and support a student if he did his duty well. Poverty was not a limiting factor, for people respected and were morally obligated to support the ideal students who subsisted by begging his daily food. Gurukula system also supported the students who resided with the Guru's family and actively participated in household chores and service to Guru. Willingness to perform activities according to his capacity developed self-reliance and identify his expertise areas. Self-reliance is the mother of self-confidence and the ancient educational system sought to develop it in a variety of ways. Educational system was such that problems such as uncertainty of the future prospects, overcrowding in a particular discipline of study, cut-throat competition in professions were unknown and did not dampen the self confidence of the students.[1]

Influence of Self-restraint

The element of self-restraint, primarily inculcated by the system, arose from simplicity in life and habits. The values of essential needs of food, clothing and shelter were significantly emphasized on. A brahmachari was to have one simple full meal (either through Bhiksha or provided by the Guru's family), and appropriate sufficient clothing (floppishness, flamboyant or grandness were not allowed). All his student life a brahmachari was taught to engage in learning skills to enable him to be an efficient and healthy grihastha in his upcoming grihasthashrama. A brahmachari was allowed to have recreations that were not to be frivolous and lead a life of perfect chastity. Thus educationalists aimed at promotion of self-restraint through development of proper habits, understanding through reasoning and value of simple lifestyle dispelling self-repression. Neither was this self-restraint enforced by correction and punishment nor by force. A brahmachari would be educated that in his next ashrama (grhastha) he would have a different set of rules to enjoy the pleasures of life, experience the bounties of food, clothing, wealth etc and so he is trained to discharge his duties carefully.[1]

Development of Discrimination and Judgment

Study of shastras like Tarka, Nyaya, Mimamsa etc promoted the powers of discrimination and judgement which are necessary for the development of proper personality. Students of such subjects are exposed to controversies involved and so are trained to view perspectives of both sides of arguments, form his judgement and defend his position in literary debates. In ancient days, education system supported healthy debates of different kinds and students greatly sharpened their intellectual skills on such occasions. Vedic students had a different intellectual exercise which required mechanical training of memory and played the important role of preserving vedic literature when paper and printing were unavailable. Thus education system promoted the development of mental skills of concentration, focus, memory, judgment, discrimination, verbal expression and healthy competition.[1]

Chores and Social Duties

While a student sharpened his mental skills, ancient educationalists also emphasized on instilling responsibility in a student by the inculcation of civic and social duties. At the gurukula, no one led a self-centered life. Students participated in community activities starting from cleaning yajna untensils, maintaining the ashrama, tending to cows and animals coexisting with them and performed agricultural duties (see Dhaumya's students). Thus humility, compassion to all, team spirit, sharing with others, self-reliance, problem-solving were the naturally and unconsciously inculcated values in them. The whole of Shikshavalli of Taittriyopanishad stresses the importance of duties of the student and the famous convocation address in 11th Anuvaka of Taittriya Upanishad, sums up the importance of these duties starting with Speaking the truth and Practicing Dharma.[5]

सत्यं वद । धर्मं चर । स्वाध्यायान्मा प्रमदः । (Tait. Upan. 1.11.1)[6]

A student is enjoined to perform his duties as a son, a husband, a father conscientiously and efficiently. His wealth is not to be utilized solely for his own or family's wants, he is taught to be hospitable and charitable with duties even to the other creatures and beings.

Professions were based on highest codes of honour, which laid stress on the civic responsibilities of their members. A physician was to serve selflessly, and a warrior was not to attack his opponent indiscriminately. Moral values were so greatly enmeshed in the social fabric that Governments were there only to monitor the larger enforcement of the system.[1]

Promotion of Social Efficiency

Education was not merely for sake of imparting cultural knowledge and its preservation nor for developing intellectual prowess without any usage. The Gurukulas were not just the centers for knowledge transfer but also trained individuals for knowledge translation (putting it to use) for development of social efficiency. Varna System was interlinked to the educational system to efficiently manage the division of work for social efficiency. The theory of division of work was mainly governed in later times by the principle of heredity. Although the rising generation could train in any branch of knowledge, profession and industry, the system directed the individual's training in more or less predetermined spheres of social duties of that family.

We have many instances where exceptional talent crossed the limits of the Varna system and selected the profession it liked; Brahmanas and Vaishyas as kings and warriors, Kshatriyas (Pravahana Jaivali, a Maharaja, taught Brahmavidya to Uddalaka and Shvetaketu who were brahmins) and Shudras (Shankaracharya gained Brahmajnana from a Chandala) were philosophers and preceptors, make their appearance throughout our ancient history.

However, it was deemed to be in the interest of the common man that he should follow his family's calling. Each trade, guild and family trained its children in its own profession. This system may have sacrificed the individual choices and educational interests of a few, but was undoubtedly in the best interest of the social fabric. An agriculturist having the practical knowledge of identifying rain bearing clouds is taught to his children and the art of warfare is best understood and experienced by the child born in a kshatriya family. Thus knowledge and profession were integrated as seen in the Varna system. Differentiation of functions and their specialization in hereditary families naturally heightened the efficiency of trades and professions thereby leading to social efficiency.[1] A holistic education pattern was seen wherein the rising generation was exposed to different branches of knowledge with specialization in family profession.

Preservation and Spread of Culture

One of the important aims of education was to preserve and spread the national heritage and culture. As seen above education was the chief means of social and cultural continuity. The vast amount of literature (including both vedic and classic subjects that are still unexplored) only mirrors this deep concern that our ancients had for the preservation and transmission of the literary, cultural and professional heritage of our race. Members of the professions were to train their children in their own lines, rendering available to the future generation at the beginning of its career, all the skill and processes that were acquired after painful efforts of the bygone generations. Svadhyaya laid down that every student (of a particular shaka of a particular Veda) was to learn at least a portion of his particular literary heritage. It was the incumbent duty of the priestly class and preceptor class to commit the whole of the Vedic literature (of a particular shaka of a particular Veda) to memory in order to ensure its transmission to unborn generations. History is witness to the fact that even this greater cause of preservation of sacred Vedic knowledge was taken by a particular section of the Brahmana community devoted to lifelong cause of learning. Manusmrti (Adhyaya 3) describes the period of learning as follows

षट्त्रिंशदाब्दिकं चर्यं गुरौ त्रैवेदिकं व्रतम् । तदर्धिकं पादिकं वा ग्रहणान्तिकं एव वा । । ३.१ । ।

वेदानधीत्य वेदौ वा वेदं वापि यथाक्रमम् । अविप्लुतब्रह्मचर्यो गृहस्थाश्रमं आवसेत् । । ३.२ । । (Manu. Smrt. 3.1 -2)[7]

Students were imparted moral values that remained with them for life. From the very young age emphasis was laid on obedience to parents, respect to elders and preceptors, gratitude to Rsis; all of which helped preserved the cultural heritage. Svadhyaya and Rsitarpana played an important role once the student entered grhastha ashrama. Svadhyaya enjoined a daily recapitulation of at least a portion of what was learnt during student life and Rsitarpana required a daily offering of tribute of gratitude to the rshis and mantradrashtas of the past, during the morning prayers. As this tradition gradually declined where very few agnihotris (those who perform morning and evening offering in Agnihotras) are practicing these days, the study of Puranas gained more popularity and developed as a community activity. Reaching out to masses through their native language, many Puranic lores though expounded the older procedures of yajnas, gradually got filtered down and only few best cultural practices remained in the present day preserved even by the illiterate population as tradition.

ऋणत्रयसिध्दान्तः ॥ Rna Siddhanta

Vedic age references speak about the Three Debts (ऋणत्रयम्) which served the purpose of instilling moral values in the younger generation to accept and maintain the best traditions of thought and action of the past generations. According to this siddhanta the moment an individual is born in this world, he /she incurs three debts, which he can discharge only by performing certain duties.

- देवऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Devatas is relieved by learning how to perform yajnas and by regularly offering them. Thus religious traditions are preserved.

- ऋषिऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Rshis of the bygone ages can be discharged by studying their works and continuing their literary and professional traditions. Thus the literary traditions are preserved.

- पितृऋणम् ॥ Debt to the Pitrs or ancestors can be repaid by getting married to raise progeny and impart education to them. Thus the family tradition is preserved.

Taittriya Samhita mentions the three debts as follows.

जायमानो वै ब्राह्मणस्तृभिर्ऋणैर्ऋणवाञ्जीयते । यज्ञेन देवेभ्यो ब्रह्मचार्येण ऋषिभ्यः प्रजया पितृभ्यः ॥ (Tait. Samh)

Steps were taken to see that the rising generation became an efficient torch bearer of the culture and traditions of the past. Body, mind, intellect and Atma constitute a human being; the aims and ideals of ancient system of education were thus to promote their simultaneous and harmonious development.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 Altekar, A. S. (1944) Education in Ancient India. Benares : Nand Kishore and Bros.,

- ↑ Manusmriti (Adhyaya 2)

- ↑ Pt. Girija Prasad Dvivedi (1917) The Manusmriti or Manavadharmashastra (Hindi Translation) Lucknow: Nawal Kishore Press (Adhyaya 2 Sloka 168)

- ↑ Mm. Ganganath Jha (1920 - 1939) Manusmrti with the Manubhashya of Medathithi, English Translation. Volume 3, Part 1 Discourses 1 and 2. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass

- ↑ Swami Gambhirananda (1989 Second Edition) Eight Upanishads with the Commentary of Sankaracharya, Volume 1 (Isa, Kena, Katha, Taittriya). Mayavati : Advaita Ashrama (Page 266)

- ↑ Taittriya Upanishad (Shikshavalli Anuvaka 11)

- ↑ Manusmrti (Adhayaya 3)