Ahamkara (अहंकारम्)

Ahamkara (Samskrit: अहंकारम्) is one of the functions of the mind. It is an indigenous Indian concept related to self and identity.[1] Inquiry concerning human nature has centered on the fundamental question 'Who am I'. The answer is the I-feeling whose nature the questioner is interested in is 'aham'.

It is considered a function of the mind or mental apparatus known as antahkarana. In the Indian tradition, the experience of personal identity or the self-sense is termed 'aham,' translated to 'I' in English. It is debatable that the term 'ego' conveys the same meaning as 'aham,' a Sanskrit term.[2]

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

Attempts at answering the question, 'Who am I,' have progressed in two distinct directions, in the Indian traditions,[1]

- inwardly through introspection and intuition

- outwardly in terms of empiricism and intellectual understanding.

Here the I-feeling is called 'aham' and it is the function of the mind or antahkarana. The function is known as Ahamkara; at the psychological level, it refers to all our day-to-day feelings and thoughts about ourselves.[2]

While modern psychology has relied exclusively on empiricism and intellectual analysis, in the Indian tradition both methods have been employed leading to findings at two levels of awareness.

- Empirical level (based on observations in the physical realm and scientific testing) - A level at which subject-object distinction operates.

- Transcendental level (beyond ordinary experience, thought or belief, non-physical realm) - A level at which subject-object distinction is transcended.

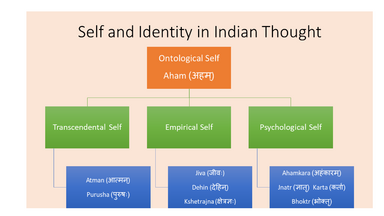

In the Indian tradition, there are many concepts related to identity and self, other than the generic term 'aham,' used in different contexts with specific meaning and significance.[1]

- Ontologically (based on existence) 'aham,' represents 'being.'

- Transcendentally, 'aham,' is referred to as Atman and Purusha.

- Empirically, 'aham,' is referred to as Jiva (person), Dehin (physical body), Kshetrajna

- Psychologically, 'aham,' is referred to as Ahamkara, Jnatr (knower), Bhoktr (enjoyer/sufferer), Karta (doer), and so on.

Ahamkara in Various Texts

Upanishads

In Prashnopanishad, ahamkara is listed along with buddhi, manas, and chitta.[1]

....मनश्च मन्तव्यं च बुद्धिश्च बोद्धव्यं चाहङ्कारश्चाहङ्कर्तव्यं च चित्तं च चेतयितव्यं च .... (Pras. Upan. 4.8)[3]

...The manas (with senses) and its objects, the buddhi (intellect) consisting in determination and its objects, ahamkara, i.e., the mind characterized by egotism and its objects, Chittam, i.e., the intelligent mind and its objects...[4]

Chandogya Upanishad speaks about ahamkara as self-sense and points out that those who fail to discriminate between atman and body will confound the self-sense with the body.

स एवाधस्तात्स उपरिष्टात्स पश्चात्स पुरस्तात्स दक्षिणतः स उत्तरतः स एवेदँ सर्वमित्यथातोऽहङ्कारादेश एवाहमेवाधस्तादहमुपरिष्टादहं पश्चादहं पुरस्तादहं दक्षिणतोऽहमुत्तरतोऽहमेवेदँ सर्वमिति ॥ १ ॥ (Chan. Upan. 7.25.1)[5]

That (infinite) alone is below; it is above; it is behind; it is in front; it is to the right; it is to the left. All this is it. Now, as regards self-sense (ahamkara): I am below; I am above; I am behind; I am in front; I am to the right; I am to the left. I am all this.[6]

Vedanta

According to Upanishads and Vedanta, all the problems start when this nonessential factor adds its influence in our life. Therefore, ahamkara is bad and we find more slokas denigrating ahamkara (Ahamkara Ninda) (14 as against 3 describing its nature) in Viveka Chudamani. Ahamkara is looked down upon with following metaphors and descriptions (Slokas 297-310):

It is vikara, dushta, rahu, powerful wild serpent, a residue of poison in the body even after it is purged from a body, a thorn in the throat of a person taking food, an enemy to be slayed with the sword of vijnana, and fashioned out of moodha buddhi (dull intellect). Even after it is completely rooted out, if it is thought for a while, it sprouts hundreds of vrttis (mental modes). It should not be given scope through sense objects even after it is completely controlled. If it is given, it is like watering a withering lemon plant that will come to life.[1]

Shrimad Bhagavad Gita

Ahamkara simply put is the feeling of "I am." It is described as the state of mind where the notion of individuality comes into play. Bhagavadgita clarifies that Karma or action, be it of temporal or spiritual class, is completely driven by the Gunas in Prakriti. Nature (Prakriti or Pradhana) is the equipoised state of the three Gunas or energies. Changing levels of these energies or Gunas bring about modifications of Prakriti, manifesting as the body-mind-sense complex.[7]

प्रकृतेः क्रियमाणानि गुणैः कर्माणि सर्वशः। अहङ्कारविमूढात्मा कर्ताऽहमिति मन्यते।।3.27।। (Bhag. Gita. 3.27)[7]

All Actions are performed, in all cases, by the three Gunas, by the modifications in the form of body and organs born of Nature. Ahankara-vimudha-atma (अहङ्कारविमूढात्मा), one who is deluded by Ahamkara, thinks, thus; 'Aham, karta, I am the doer.' Ahankara is self-identification with the aggregate of body and organs. He whose atma, mind, is vimudham, deluded in diverse ways, by that (ahankara) is ahankara-vimudha-atma. He who imagines the characteristics of the body and organs to be his own, who has self-identification with the body and the organs, and who, through ignorance, believes the activities to be his own, he thinks, 'I am the doer of those diverse activities.'[7]

Ahamkara - Self and Identity

The fundamental questions - who identifies with non-self, who has to discriminate between non-self and Self, and who has to consciously attempt to dis-identify with non-self, have always challenged the mankind. Ancient Indian seers posit ahamkara, regarded as one of the antahkaranas ("the inner instrument," mind) as the one involved in this process.[1] Schools differ in the number of functions included under antahkarana.

| Manas | Sankhya named it Antahkarana. Yoga named it Chitta | Nyaya named the three components Manas | Vedanta named all four together as Antahkarana. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhi | |||

| Ahamkara | |||

| Chitta |

Ahamkara manifests as the "me" in each person. Personal identity or the self-sense is its defining characteristic. It is the source of the distinction between the self and the other.

Origin of Ahamkara

Samkhya darshana vividly enumerates the 25 tattvas and the manifestation of the Universe. In laying out the sequential order of origin of various elements (Panchamahabhutas and so on) according to Samkhya,

... प्रकृतेर्महान्महतोऽहंकारोऽहंकारात्पञ्च ... (Samk. Darsh. 1.61)[8]

Summary: Prakriti caused mahat, described as the Hiranyagarbha of Veda or the state which developed into the primordial fireball of the modern science. Mahat in turn gave rise to Ahamkara.[9]

Though the traditional or conventional meaning of Ahamkara is taken as ego or conceit, the Samkhya expression communicates the meaning of "individuality of self." It is this sense that it covers the entire lot of manifestations collectively known as the Jagat. All manifestations, without exception, emerged from Mahat possessing one fundamental characteristic of being unique in creation. In the visible human world, each person uses the term I for his/her own self, excluding even the near and dear ones.[9]

In the Bhagavadgita, Shri Krishna mentions Ahamkara as one of the eight-fold Prakriti of divine nature.

भूमिरापोऽनलो वायुः खं मनो बुद्धिरेव च। अहङ्कार इतीयं मे भिन्ना प्रकृतिरष्टधा।।7.4।। (Bhag. Gita. 7.4)

This Prakrti is divided eight-fold thus: earth, water, fire, air, space, mind, intellect and also egoism.

Tattvabodha describes Ahamkara as अहंकर्ता अहङ्कारं । Ahamkara is of the nature of the notion of doership.

Nature and Function of Ahamkara

Nature and function of ahamkara are lucidly explained in Viveka Chudamani of Shankaracharya. Shankaracharya defines ahamkara, thus:

अन्तःकरणमेतेषु चक्षुरादिषु वर्ष्मणि । अहमित्यभिमानेन तिषठत्याभासतेजसा ॥ १०५ ॥

Antahkarana itself dwells in the sensory and motor organs and in the body as aham with abhimana (अहमित्यभिमानेन) in the reflected brightness of atman.[1]

अहङ्कारः स विज्ञेयः कर्ता भोक्ताभिमान्ययम् । सत्त्वादिगुणयोगेन चावस्थात्रयमश्नुते ॥ १०६ ॥ (Vive. Chud. 105-106)[10]

Meaning: Know that it is ahamkara, which due to abhimana (identifying itself with the body) becomes karta (doer) and bhokta (enjoyer) and in its association with sattva and other gunas will assume avasthatraya (the three states of waking, dream and sleep).[1][11]

विषयाणामानुकूल्ये सुखी दुःखी विपर्यये । सुखं दुःखं च तद्धर्मः सदानन्दस्य नात्मनः ॥ १०७ ॥ (Vive. Chud. 107)[10]

Meaning: When the sense-objects are favorable it (Ahamkara) becomes happy, and it becomes miserable when the case is contrary. So happiness and misery are the characteristics of Ahamkara (egoism) and the not of the ever-blissful Atman.[11]

From this text it is clear that ahamkara is the cause of a Jiva's experience of happiness and sadness under favorable and unfavorable circumstances and therefore sukha and dukkha are the dharmas of ahamkara and not that of atman which has Ananda as its characteristic. Thus ahamkara is related to the bio-psycho-social aspects of human nature. Abhimana (identification with I-sense) is the essence of ahamkara.[1] According to Sankhyan cosmogony, the Mahat (or intellect) gives rise to the Ahamkara in the Purushas, which manifests in a persistent tendency towards, self-preservation and self-assertion of individual beings.

Prof. Rao describes Ahamkara in modern terms as follows:

The general consciousness which is undifferentiated and rudimentary in course of time gets individuated. It acquires a subjective frame of reference and the process of individuation is afoot. This state, a further development of the capacity to be conscious of objects may be designated as self-consciousness. The Samkhya theory has brought into currency, the expression―ahamkara” to denote this. This is a word which superficially signifies "I making."

Of Bondage and Release from Punarjanma

Vivekachudamani enlightens us about the bondage of man and karmik cycle.

अत्रानात्मन्यहमिति मतिर्बन्ध एषोऽस्य पुंसः प्राप्तोऽज्ञानाज्जननमरणक्लेशसम्पातहेतुः । येनैवायं वपुरिदमसत्सत्यमित्यात्मबुद्धया पुष्यत्युक्षत्यवति विषयैस्तन्तुभिः कोशकृद्वत् ॥ १३९ ॥ (Vive. Chud. 139)[10]

Summary: The misconstrual of the non-self as self ties a man to egoism, and it is this tie (bandha) which leads to the suffering of the cycle of birth and death. Having considered the body to be real and construing it to be the “me,” the jiva nurtures it and protects it by following its desires. The ego thus becomes trapped in a reality of its own (mis)construal-like a moth in its cocoon.[12]

According to Sankhya, Purusa mistakenly identifies itself with the conditions of the Antahkarana Chatushtaya, and undergoes the various emotions of happiness etc., in endless cycles. It is possible, however, for the individual to use the inherent capacity for knowledge or correct discrimination, and to realize that true selfhood involves being the uninvolved witness, as purusa is in its nascent state. This implies that the end of suffering involves going beyond both pleasure and pain, elation and depression. Such is the ideal state of the “isolation” (kaivalyu), according to Sankhya.[12]

Components of Ahamkara

Four sub-concepts of ahamkara based on Indian tradition have been described by recent scholars:

- individuality (vaishishtya)

- separation-differentiation (dvaita bhava)

- agency or doership (kartatva)

- identification (abhimana)

While ‘individuality’ represents uniqueness, ‘separation-differentiation’ marks the feeling of being different from others, ‘agency’ signifies the sense of doer-ship and ‘identification’ indicates relationship with worldly objects, involving associations and companionship (sanga), attractions and attachments (moha) and mineness or ownership (mamkara).[1] Ahamkara is an expression of exclusivity, the self of the person using it, excluding the other person. This exclusive distinctiveness is the dominant characteristic of the creation, be it physical or biological. Each unit of creation enjoys its individuality among the whole mass of physical existence. Each piece of creation, big or small, bears its originality, just like the thumb impressions of individuals, there are no duplicates. Ahamkara is the identity mark of creation.[9] This uniqueness of creation extends to the entire process of creation. No two stars or planets are the same, neither is the period of their duration, nor their distances. The same is the state of being of all atoms, molecules or compounds. No two days are the same nor any two nights, the reach of Ahamkara covers past, present and future.

Ahamkara in different schools

Ahamkara is the root of all vrittis or mental modifications. Destruction of ahamkara leads to removal of kleshas and all the mental modes of psychosis will die automatically. Different schools of thought suggested different ways for the removal of ahamkara.[13]

- Advaita school of thought advocates that ahamkara can be burnt by the fire of Jnana (knowledge).

- Visishtadvaita recommends devotion and self-surrender.

- Yoga sutras prescribe deep meditation.

Advaita asks interested persons to focus directly on the texts such as Upanishads, to help discriminate the transcendental Self beyond his or her Ahamkara (which is wrapped in ongoing thoughts and emotions). Both Advaita Vedantins, as well as, the Sankhya Yoga systems consider Ahamkara to be the seat of pleasure and pain rather than the true Self.[12]

Srinivasan, interpreting the views of the Visistadvaita Vedanta of Ramanuja, states thus, ‘Ahamkara is characterized by the contracted consciousness of the individual whereby he imposes on himself artificial and ego-centric “separative” limitation, conceives himself as divided from “God” and opposed to other individuals and lands himself in a state of struggle and suffering in the pursuit of selfish desires. This is the state of human bondage or inauthentic existence. Only by transcending this state of ahamkara can the true status of the individual soul be realized.’[1]

Ahamkara and Personal Growth

In layman's language, Ahamkara is commonly referred to as False ego, Pride, or Arrogance. But the spiritual understanding of Ahamkara lies beyond such terms. For example, ‘Ego’ refers to an individual’s sense of self-esteem. ‘Pride’ refers to an individual’s feeling of deep pleasure or satisfaction from one’s achievements. ‘Arrogance’ on the other hand refers to an individual’s exaggerated sense of self-importance.[2]

In a child Ahamkara is faint but it develops day by day by the accumulation of desires, fears, Vasanas etc.[13] As a person ages due to various external and internal influences the behaviour and character is shaped. In Western Psychology, 'Ego' occupies the center stage and function whereas in the Indian tradition, 'Atman' or consciousness as-such is the fundamental principle of awareness and is not a manifestation of the mind. Ahamkara, on the other hand, a manifestation of the mind shrouded by Avidya masquerades as the self. Therefore, removing the veil of ignorance, taming the ego, transcending the limiting adjuncts of the mind to allow the true light of consciousness to reflect on the mind of the person becomes the focus of Indian psychology. This is what is involved in the process of transformation of the person as part of growth.[14]

Sri Aurobindo elaborates that this process of ego-transformation includes three intrapsychic processes, viz., aspiration, surrender and rejection. Aspiration denotes the driving force to feel the presence of divine and access Atman; it is a motivating factor. Surrender refers to the openness to witness consciousness as-such without prior notions, attitudes and expectations. Rejection involves rejection of all ego based accumulations that tend to cloud the faculties which help to reveal the Atman. Thus transformation involves tracing back to the true Self in the Nivritti marga, controlling cravings and attachments and dispelling Avidya.[14]

The dominant ideal of human development in Western tradition from Aristotle through Abraham Maslow and Erik Erikson is self-actualization, which involves continuous unfolding of hidden potentials. It is a relentless pursuit to increasingly satisfy images of who one might become in future. But the ever-changing image leaves open the possibility that the self-identity one may discover is the wrong one. By and large modern Western psychology has highly valued the actualization of human potential through a process of growth indicating continual change for something better in any form of human endeavor. The emphasis is on 'becoming' rather than on 'being'; it implies that one always tries to become different from what one is currently. In Indian psychology, we find constant emphasis on 'being.' There is a serious attempt to find out what is within oneself through the past, present and future times. All concepts suggest towards an ideal stable state or stasis, a final point where one does not have to move from expecting some change for better.[14]

In Western psychology we find more attention paid to ego-adjustment than ego-transformation. Therefore, the discussions often revolve around defense mechanisms. The general psychotherapeutic approach in the current Western mainstream tradition is horizontal, traveling across the existential contours of the ego. The Indian perspective is vertical, elevating the person from the tangled ego to the sublime heights of the self, and achieving this state of pure consciousness has healing and transformational consequences to the person.[14]

Ahamkara Vs Ego

Ahamkara is loosely translated to ‘Ego’ in English language.[15] The term ‘Ego’ was popularized from Freudian theory of Personality, which emphasized the three structures of mind i.e., Id-Ego-Superego, in which ego plays an executive role in balancing Id and Superego.[2]

Ego, in psychoanalytic theory, is that portion of the human personality which is experienced as the “self” or “I” and is in contact with the external world through perception. It is said to be the part that remembers, evaluates, plans, and in other ways is responsive to and acts in the surrounding physical and social world. Freudian 'ego' was an approach to understand the self and behavior in terms of the external world, whereas the Indian 'ahamkara' refers to the inherent I-ness, in terms of the internal experience of individuating principle, a feeling of distinction and uniqueness.[2]

Freud and other early psychoanalysts used the concept of ego to include both the identity sense as well as other functions collectively referred to as a secondary thinking process. Later day scholars like Bellak considered sense of identity or self sense (ahamkara in the Indian context) as one of the 12 Ego functions. The term 'self' was used to refer to the sense identity while retaining the term 'ego' for the many secondary process functioning of the mind. According to Kiran Kumar, the concept of ahamkara and the concept of self as proposed by self-psychologists are nearer to each other than the psychoanalytic concept of ego functions.[1]

In modern psychology due to non-recognition of the possibility of a transcendent Self (which is regarded as true Self), all the discussions on self terminate at the level of bio-psychosocial identity. Neither Atman nor jiva are accepted as real. Therefore, the notions like life after death, reincarnation, and transcendence are viewed with suspicion. Western psychoanalysts find it difficult to appreciate the possibility of transcendence because it involves going beyond the personal identity or ego. In this context, of far reaching clinical significance is the debate that attempts at transcendence lead to psychopathology. Kiran Kumar (2005) clarifies that such issues are semantic in nature and they arise due to incorrect translation of concepts from one language to another. For example, Upanishads exhort that one should lose ahamkara (the sense of false identity) which is a manifestation of the mind and not buddhi or vijnana in order to realize the atman (consciousness), which is the true identity. In this process of discriminating between anatman (non-Self) and Atman (Self) buddhi or vijnana plays an important role. Indian traditions have emphasized that one should go beyond the limited false identification which masks the true Self, but certainly not lose those ego-functions which keep a person sane.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Salagame, Kiran Kumar. "Concept Ahamkara: Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” In K. R. Rao & S. B. Marwaha (Eds.) Towards a spiritual psychology: Essays in Indian Psychology. (pp. 97-122). New Delhi: Samvad India Foundation. 2005.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Tayal, N & Sharma N. R. Comparative view of the eastern and western perspectives on the concept of Ahamkara/Ego. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, Vol 8, Issue 3, July- Sep, 2020. DOI: 10.25215/0803.065

- ↑ Prashna Upanishad (Prashna 4)

- ↑ Sastry, Sitarama. S. trans. (1923) Katha and Prashna Upanishads, and Sri Sankara's Commentary. Vol. 2. Madras: The India Printing Works. (Pages 147-148)

- ↑ Chandogya Upanishad (Adhyaya 7)

- ↑ Swami Swahananda (1956) The Chandogya Upanishad, containing the original text with word-by-word meaning, running translation and copious notes. Madras: Ramakrishna Math. (Page 539-542)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bhagavad Gita (With Translations)

- ↑ Samkhya Darshana (Full Text)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Verma, Keshav Dev. Vedic Physics. 1st ed. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass, 2008. (Pages 23-25)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Viveka Chudamani

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Swami Madhavananda. Vivekachudamani of Sri Sankaracharya, Text with English Translation, Notes and an Index. Almora, Mayavati, India: The Advaitha Ashrama, 1921. (Page 43)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Paranjpe, Anand C. Self and Identity in Modern Psychology and Indian Thought. Path in Psychology Ser. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1604/9780306471513.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Safaya, Raghunath. (1976) Indian Psychology, A critical and historical analysis of the psychological speculations in Indian Philosophical Literature. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (Pages 325-326)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ↑ Salagame, K. K. K., & Raj, A. (1999). Ahamkara and ego functions among meditators and normals. Journal of Indian Psychology, 17(1), 46–55.