Sadhana and Indian Psychology (साधनं मनोविज्ञानं च)

Sadhana begins with the consciousness of the existence of some Supreme Power, an intimate connection or rather a conscious union with which is deemed absolutely essential to the realisation of the summum bonum of life.[1]

This Supreme Power has sometimes been regarded as the Higher Self of man himself and not any foreign power with whom only an external connection could possibly be established. Sadhana, thus means the conscious effort at unfolding the latent possibilities of the individual self and is hence limited to human beings alone. Only in man is the special equipment, viz. a conscious effort apparently separate from the activities of nature, comes into being.[1]

Indian psychology, is a system of psychology that is rooted in classical Indian thought and is implied in numerous techniques prevalent in the subcontinent for psycho-spiritual development such as the various forms of yoga.

Concept of Self in Indian Psychology

Indian "Person" - Composite of Sharira, Manas and Atman

Indian psychology involves the study of the person. The person is conceived as a composite of body (Sharira), mind (Manas), and consciousness (Atman). Ayurveda texts present a similar definition of a person. With regard to their role in psychological processes, the terms may refer to the following.[2]

- Body refers to the nervous system, the senses (Indriyas), and associated structures connected with the brain.

- Manas (loosely translated as mind) is the hypothetical cognitive instrument related to the body at one end and consciousness at the other.

- Consciousness is conceived to be irreducibly distinct from body and mind. It constitutes the nonphysical aspect of the person.

Body, mind, and consciousness are not only conceptually distinct, but are also mutually irreducible in the human context. Consciousness is qualitatively different from the body and the mind with which it may be associated. For this reason, though it is associated with a mind at a given time, it does not interact with it. The body and the mind, unlike consciousness, are physical; and they can interact with each other and are influenced by each other. However, it is important to note that a mind cannot be reduced into its physical constituents and a body cannot be transformed into a mind even though they influence each other within a person. They function differently. From this perspective, the body is conceived as gross matter that permits disintegration. However, mind being a subtle form of matter is not constrained by spatiotemporal variables in the same manner as the gross body does. The body disintegrates irretrievably at death. The mind, however, has the potential to survive bodily death (Rao 2014b).[2]

Many scholars, in the recent decades have studied and presented the concept of Self based on Indian perspectives given in the Vedas, varna and ashrama dharmas, samskaras, in the philosophical texts such as the shad-darshanas, the Brahmasutras, the Upanishads, the Itihasas, the Puranas and Tantras etc., all of which influence the Indian psychological make-up.[3]

Metaphysical Self

In Indian psychology the person, is a unique composite of consciousness, mind, and body. Consciousness is the source of subjectivity and the very base of one’s experience of being, knowing, and feeling. The term that signifies the person in Indian psychology is jīva. Jīva as a psychological concept is different from purusha, a metaphysical entity.

A review of the study of self in India reveals that indeed the core of Indian self is metaphysical, and it has been the focus of study by philosophers as well as psychologists. Thus we find a general agreement that the metaphysical Self, Atman, is the real Self and it is embodied in a biological or physical body which constitutes the Jiva or the physical Self.

Varna and Ashrama System and Social Self

The metaphysical self, Atman is embodied in a biological or physical self, and through the varna system right at birth, the biological self acquires a social Self. With changing times though there is little adherence to the ashrama system on a mass scale, the idea and social construct still persists. With advancing age it is still not unusual for people to start slowing down on their worldly commitments and pass on the baton to the next generation.[3]

Depending on which phase of life one is in, the Self is viewed differently. Lifestyle completely changes from phase to phase of the ashrama system. For example, as a student one ate less (alpahari), as a grhastha there was no restriction on food, as a vanprastha he ate fruits and roots and as a sanyasi he begged for food and ate unconcernedly about taste. Varna and Ashrama dharmas clearly defined one's occupation and role in the society and therefore, the Indian concept of Self is socially constructed and varies with occupation and stage of an Indian.[3]

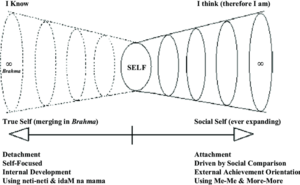

When Atman attains unity with the Supreme Being, brahman, and this realization or anubhuti is the goal of the human being. In that paradigm, when one experiences the real self, one experiences boundlessness or infinite state of supreme being. In other words, much like the social self that has the potential to grow infinitely, the real self has the potential to be limitless. Thus, the Indian concept of self expands to be infinite socially and contracts socially for the true self to expand to be infinite metaphysically. This conceptualization of the self is critical to the understanding of psychological processes in the Indian cultural context.[3]

Physical, Psychological and Metaphysical Self based on Panchakoshas

The various concepts of Self, are well grounded in various Indian philosophical and vedantic texts. The metaphysical self is most commonly visualized as Atman, which is situated in a living being as a result of past karma. The physical self can further be classified as sharira-traya (the three bodies - sthula, sukshma and karana shariras) or panchakoshas (constituting - annamaya, pranamaya, manomaya, vijnanamaya and anandamaya koshas). While social self is manifested by the various beings in different ways at different proportions, human beings are believed to be the only ones who can pursue moksha (or liberation), enlightenment, jnana (or knowledge), or self-realization. Based on the Panchakoshas presented in the Taittriya Upanishad the following classification gives rise to a model of Self having the following elements.[3]

| Self | Kosha | Elements | Functions | Factors Affecting Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metaphysical Self (the I-ness) - Subtlest | Anandamaya Kosha | Jivatma (Atman Embodied) | Kartrtva (doer) and Bhoktrtva (enjoyer) | Sadhana margas

Yoga etc. |

| Psychological Self (Mental and Cognitive faculty) Subtle | Vijnanamaya Kosha | Buddhi (the discriminative decision making faculty) | vijñāna—understanding, knowing, direct cognition, wisdom, intuition and creativity. | Sadhana margas

Yoga etc. |

| Manomaya Kosha | Manas, (the cognitive faculty) Antahkarana

Ahamkara |

understanding,

thoughts, ideas perception, processing the inputs of sense-organs | ||

| Physical Self (Physiological

and Physical faculties) Gross |

Pranamaya Kosha | Physiological functions of the body | Functional aspects of the body such as breathing, excretion, digestion etc. | |

| Annamaya Kosha | The physical body made of several constituents | Human body and its parts such as, tissues, bones, skin, organs etc. |

Sadhana and The Psychological Self

The inwardly directed individual Self perceives vaguely its latent infinitude and realises gradually that its limitation and bondage are not inherent in its nature but are rather imposed on it, and wants somehow to shake them off and thus realise its full autonomy. Liberation or vimukti is identical with freedom, and freedom is expansion. It is the gross outward matter and contact with matter that have made the Self appear limited. The deeper and deeper we dive into Self, the more of expansion, freedom and light do we feel and enjoy. The conscious urge of the finite to become more and more expanded till it realises its infinitude is what is really meant by mumukshutva (desire for liberation) which forms the unmistakable first step in the course of, Sadhana.[1]

Sadhana Margas

Karma Marga

Jnana Marga

The objective of life is to experience the ultimate ontological truth - Self is Brahman - and the way to pursue it is through vairagya (renunciation) captured by the attributes of knowledge (Sadhana by Jnana-marga) is presented in the thirteenth adhyaya of Bhagavadgita. In other words, epistemology or the Indian theory of knowledge is to be able to live and experience the ontological belief that brahman is in everything in the universe, and it is practiced through a meticulous lifestyle filled with positivity.[4]

Bhagavadgita presents the all positive psychological elements or characteristics that everyone needs to cultivate to be able to learn the knowledge of Brahman. These elements of Jnana include[4]

अमानित्वमदम्भित्वमहिंसा क्षान्तिरार्जवम् । आचार्योपासनं शौचं स्थैर्यमात्मविनिग्रहः ॥ १३-८॥

इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यमनहङ्कार एव च । जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ १३-९॥

असक्तिरनभिष्वङ्गः पुत्रदारगृहादिषु । नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ १३-१०॥

मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी । विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ १३-११॥

अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वं तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् । एतज्ज्ञानमिति प्रोक्तमज्ञानं यदतोऽन्यथा ॥ १३-१२॥ Bhaga. Gita. 13. 8-12)

Shri Krishna lists that the characteristics mentioned (in these shlokas) constitute Jnana and those opposite to these are termed as Ajnana.[4]

- अमानित्वम् ॥ humility

- अदम्भित्वम् ॥ pridelessness

- अहिंसा ॥ nonviolence

- क्षान्तिः ॥ tolerance

- आर्जवम् ॥ simplicity

- आचार्योपासनम् ॥ service to a spiritual teacher

- शौचम् ॥ cleanliness

- स्थैर्यम् ॥ steadfastness

- आत्मविनिग्रहः ॥ self-control

- इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यम् ॥ desirelessness in the sense pleasures

- अनहङ्कारः ॥ without ego

- जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ remembering the problems of birth, death, old age, disease, and miseries that go with the physical body (to motivate oneself to think about the Atman)

- असक्तिः ॥ without attachment

- पुत्रदारगृहादिषु अनभिष्वङ्गः ॥ without fondness towards son, wife, or home etc.

- नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ constancy in a balanced manas or citta (or mind) or having equanimity of the mind in attainment of favorable or unfavorable consequences

- विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ preferring solitude having no desire to associate with people

- मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी ॥ unwavering offering of unalloyed devotion to kRSNa

- अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वम् ॥ Constant dwelling on the knowledge pertaining to the Self

- तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् ॥ Contemplation (on the goal) for the attainment of knowledge of the truth

Bhakti Marga

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 61-75)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. New Delhi Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Pages 5 - )

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 65 - )

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 170-171)