Difference between revisions of "Sadhana and Indian Psychology (साधनं मनोविज्ञानं च)"

(→Indian Concept of Self: added content) |

(adding content) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Sadhana (साधनम्)|Sadhana]] begins with the consciousness of the existence of some Supreme Power, an intimate connection or rather a conscious union with which is deemed absolutely essential to the realization of the ''summum bonum'' of life.<ref name=":5">Brahma, Nalinīkānta. ''Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā.'' United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 61-75)</ref> | + | [[File:Paths in Human Life.png|right|frameless|379x379px|Courtesy: Prof. Dharm Bhawuk]] |

| + | [[Sadhana (साधनम्)|Sadhana]] begins with the consciousness of the existence of some Supreme Power, an intimate connection or rather a conscious union with which is deemed absolutely essential to the realization of the ''summum bonum'' of life.<ref name=":5">Brahma, Nalinīkānta. ''Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā.'' United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 61-75)</ref> | ||

| − | This Supreme Power has sometimes been regarded as the Higher Self of man himself and not any foreign power with whom only an external connection could possibly be established. Sadhana, thus means the conscious effort at unfolding the latent possibilities of the individual self and is hence limited to human beings alone. Only in man a special equipment, viz. '''a conscious effort''' apparently separate from the activities of nature, comes into being.<ref name=":5" /> | + | This Supreme Power has sometimes been regarded as the Higher Self of man himself and not any foreign power with whom only an external connection could possibly be established. Sadhana, thus means the conscious effort at unfolding the latent possibilities of the individual self and is hence limited to human beings alone. Only in man a special equipment, viz., '''a conscious effort''' apparently separate from the activities of nature, comes into being.<ref name=":5" /> |

Indian psychology, is a system of psychology that is rooted in classical Indian thought and is implied in numerous techniques prevalent in the subcontinent for psycho-spiritual development such as the various forms of yoga. | Indian psychology, is a system of psychology that is rooted in classical Indian thought and is implied in numerous techniques prevalent in the subcontinent for psycho-spiritual development such as the various forms of yoga. | ||

| − | == Indian Concept of Self | + | == Opposing Social and Spiritual Dimensions == |

| − | + | [[File:Indian Concept of Self - Social and Spiritual Dimensions.png|right|frameless|332x332px]] | |

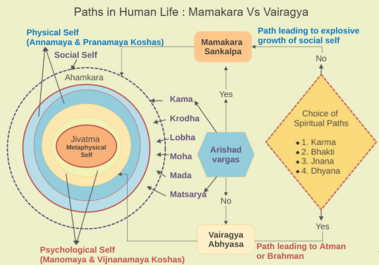

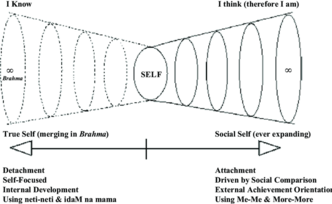

| + | While understanding the [[Indian Concept of Self|Indian concept of Self]], it was studied that the expansion of self happens in two directions. When the manas or mind turns outwards and in association with sense-organs, driven by desires (sankalpas) and attachments (mamakara), there is an explosive growth of social self. Thus, the physical self gets integrated with the social self in the social system. Jiva gets entangled in various aspects of social identities such as varna, ashrama, national and regional identities. Besides these there are other elements of self that get added to the identity box as one advances in career, and acquire wealth, a house, special equipment and professional success. A person gets caught in the web of kama, krodha, lobha, moha, mada and matsara, (arishadvargas or six enemies) which alter his psychological make-up. Indulgences to gratify various needs, further draws a person towards the ego-enhancing objects and luxuries. All these lead to an endless, perhaps infinite, growth in our social self.<ref name=":0">Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) ''Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita.'' New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 65 - 91)</ref> | ||

| − | + | When one stops worrying about the fruits of one’s efforts, performs one’s duties by controlling the senses with the manas, and allows the karma-indriyas to perform their tasks without any anxiety, then slowly one begins to withdraw from the hustle and bustle of the world and begins to be inner centered. Thus, the social self starts to lose its meaning for the person, for it is an external identity, and the person begins to be anchored inside, on the inner self, following this path. In this journey towards the ''self (atman)'', the physical self and social self start to slowly melt, and when the intellect of the person becomes stable, then one realizes the Atman or the real self. <blockquote>प्रजहाति यदा कामान्सर्वान्पार्थ मनोगतान् । आत्मन्येवात्मना तुष्टः स्थितप्रज्ञस्तदोच्यते ॥ २-५५॥ (Bhag. Gita. 2.55) </blockquote>Meaning: When a man completely casts off, O Partha, all the desires of the mind, and is satisfied in the (inner) ''self'' by the self (mind), then is he said to be one of steady wisdom. | |

| − | + | This melting of the self is just the opposite of the explosive growth of the social self.<ref>Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) ''Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita.'' New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 103-104)</ref> Thus, the Indian concept of self expands to be infinite socially and contracts socially for the true self to expand to be infinite metaphysically. This conceptualization of the self is critical to the understanding of psychological processes in the Indian cultural context.<ref name=":0" /> | |

| − | + | == Role of Psychological Self in Sadhana == | |

| + | The Self (defining which is based on the sampradaya) is not ordinarily realized by us because of its extreme fineness and minuteness. The Buddhi is to acquire microscopic vision (drsyate tvagryaya buddhya) through repeated acts of concentration if it is to have an intuition of the Self. The whole aim of Sadhana in the Indian traditions with its innumerable details (which seem very often useless and unmeaning) is to gradually educate the mind towards concentration. It enjoins rigid discipline, scrutiny in every action (from waking up in the morning till retiring in the night) and emphasizes upon minute and detailed regulation of life. It may appear meaningless or even absurd to many, however, such practices offer the required training to a novice whose mind takes interest in everything presented to it and diffuses its energy. It should be noted that many disciplinary practices are not enjoined for all, there are exemptions based on many factors including the capacities of different individuals. Shruti emphasized that the real Self can be attained through the mind and mind alone.<blockquote>मनसैवानुद्रष्टव्यं नेह नानास्ति किं चन । मृत्योः स मृत्युमाप्नोति य इह नानेव पश्यति। बृह. ४,४.१९ ॥ (Brhd. Upan. 4.4.19)</blockquote>This Brahman must be realized by the mind alone after steady and constant reflection. In Brahman that is to be realized, there is no duality or diversity. He who sees here, as though it were many, goes from death to death (attains the cycles of samsara).<ref>Dr. N. S. Ananta Rangacharya (2004) ''Prinicipal Upanishads, Volume 3, Brhdaranyakopanishat. Text, English Translation and Brief notes according to Sri Ranga Ramanujamuni.'' Bangalore: Sri Rama Printers (Pages 311)</ref> | ||

| − | + | The inwardly directed individual ''self'' perceives vaguely its latent infinitude and realizes gradually that its limitation and bondage are not inherent in its nature but are rather imposed on it, and wants somehow to shake them off and thus realise its full autonomy. Liberation or vimukti is identical with freedom, and freedom is expansion. It is the gross outward matter and contact with matter that have made the ''self'' appear limited. The deeper and deeper one dives into ''self'', the more of expansion, freedom and light does one feel and enjoy. This conscious urge of the finite to become more and more, expands till it realizes its infinitude - is what is really meant by mumukshutva (desire for liberation) which forms the unmistakable first step in the course of, Sadhana.<ref name=":5" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The course of discipline or Sadhana strengthens the finite consciousness step after step and gradually unfolds the infinitude that was all along latent in the same. Sadhana, is completed when no foreign element, no matter, no ‘other,’ remains as an unresolved contradiction or opposition, and when the ''self'' has established its sovereignty not by opposing itself to matter, but by resolving matter completely unto itself.<ref>Brahma, Nalinīkānta. ''Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā.'' United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 46-48)</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Paths of Sadhana == | |

| + | [[Sadhana (साधनम्)|Sadhana]] can be performed in different ways and as such broadly it involves either or both of the two paths - mental or physical, but the eventual change it brings about is in psychological status of the sadhaka. The value of the different forms of Sadhana are best understood, if we consider the respective contributions of each, Karma, Bhakti and Jnana, towards the development of the Sadhaka for the attainment of his goal. They are not to be regarded strictly as independent forms of Sadhana in the sense that only one of them is sufficient for the attainment of the goal. These three are intimately connected with one another, and the co-operation of all of them is necessary for the realisation of the ideal. Modern Psychology no longer believes in the compartmental division of the Faculty Psychologists, but firmly establishes the inter-connection of the various aspects of the mind. Over-emphasis or undue focus on only one aspect eclipses or paralyzes the mind of a sadhaka, and is best avoided. The keyword is achieving moderation or balance and the best path is usually very personal based on the sadhaka's temperaments, his/her personal merits and deficiencies where improvement is required to achieve the goal. This working in moderation is also emphasized in the Gita where we find Yoga described as ‘samatvam’ (balance). The natural bent or aptitude determines the particular line of Sadhana for every particular Sadhaka, but it is never to be forgotten that the particular line is merely an occasion or the main support for the development of all the different aspects.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| − | + | According to Dr. Nalinikanta Brahma, Karma, Bhakti and Jnana may be regarded as disciplines suiting three different stages in the course of development of the Sadhaka. All controversy arises when this aspect of mutual co-operation is lost sight of, and undue importance or unmerited neglect is accorded to one or other of these aspects. Shrimad Bhagavata Purana, mentions that for a Sadhaka,<blockquote>तावत् कर्माणि कुर्वीत न निर्विद्येत यावता । मत्कथाश्रवणादौ वा श्रद्धा यावन्न जायते ॥ ९ ॥ (Bhag. Pura. 11.20.9)</blockquote>Karma has to be performed until one does not feel dissatisfied (towards it) and after attaining a faith by listening to the divine stories etc., (either for bhakti or jnana), all karmas should be renounced.<ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | + | Karma has very often been downplayed by the advocates of jnana and bhakti. Karma (specifically those proceeding from desires) and jnana are incompatibles, declare the advocates of Jnana-marga, as one is the result of ignorance (avidya) and the other involves true knowledge (vidya). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Karma Marga - Attainment of purification of sharira and manas=== | |

| + | The earliest form of [[Sadhana (साधनम्)|Sadhana]] advocated by the Vedas is [[Karma (कर्म)|Karma]]. In this path of sadhana we may note different routes taken by various texts. | ||

| − | # | + | # Karmas which include the Vaidika yajnas (dravya-yajnas), vidhis to propitiate the deities (Mimamsa), upasanas (mental processes), tantra etc., to attain results such as residence in the higher worlds, but not freedom (moksha). |

| − | + | # Ashtanga-yoga system includes regulation of physical and physiological (bodily) processes to control the vrittis of the manas. | |

| − | # | + | # Tantras lay special emphasis on the process to control the Shat-chakras and Sushumna nadi for spiritual progress. It also combines elements of yoga, worship, prayer and meditation for purification. |

| − | # | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | In this path of sadhana, physical actions are performed (including daily worship, chores and ritualistic acts) such that they ultimately lead to a state of '''desirelessness'''. Of the [[Shad Darshanas (षड्दर्शनानि)|six astika darshanas]], Purva [[Mimamsa Darshana (मीमांसादर्शनम्)|Mimamsa]], founded by Maharshi Jaimini, is engaged with Karma, mainly with respect to the various [[Yajna (यज्ञः)|yajnas]]. Such rites and ceremonies advocated in this darshana shastra are limited in that they grant the performer (yajamana) a place of residence in swargaloka but are incompetent to award [[Moksha (मोक्षः)|moksha]]. | |

| − | + | The [[Puranas (पुराणानि)|Puranas]] and [[Smrti (स्मृतिः)|Smrtis]] use the term to mean such actions as daily worship (sandhya etc.), fixed religious observances, fastings, etc., and divide all such karmas into three groups, viz., nitya, naimittika, and kamya based on the periodicity and goal of such actions. Such mental processes as meditation and reflection (dhyana and vichara) are generally excluded from the province of Karma by the Vedantists. Almost all the Vedantic thinkers, however, agree in holding that only nitya karmas are useful towards jnana (by removing obstacles), kamya karmas being always excluded as they give rise to karmaphala that become positive hinderence to jnana.<ref name=":1">Brahma, Nalinīkānta. ''Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā.'' United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Pages 91- 116)</ref> | |

| − | + | The Sadhaka has to begin with karma, that being perfectly suitable to the beginner who is not yet purified in body and mind. It is karma that purifies the mind of the Sadhaka and makes him fit for the acquisition of higher truths. Adishankaracharya stresses that <blockquote>अपेक्षते च विद्या सर्वाण्याश्रमकर्माणि नात्यन्तमनपेक्षैव। ...उत्पन्ना हि विद्या फलसिद्धिं प्रति न किंचिदन्यदपेक्षते उत्पत्तिं प्रति तु अपेक्षते (Shankara Bhashya on Brahma Sutras 3.4.26)</blockquote>All karmas (yajnas and related rituals) are useful for origination of knowledge. Even the scriptures prescribe them as they serve an indirect means to the attainment of knowledge.<ref>Brahmasutras by Swami Sivananda (Shankaracharya's Bhashyam on [https://www.swami-krishnananda.org/bs_0/Brahma.Sutra.3.4.html सर्वापेक्षा च यज्ञादिश्रुतेर् अश्ववत् । ( ब्रसू-३,४.२६ । )]</ref> | |

| − | + | There is incompatibility of jnana and karma only when jnana had been reached and not before that stage. That each jnana and karma margas have their own place in a Sadhaka's life, is reinforced in Shrimad Bhagavadgita<blockquote>श्रेयान्द्रव्यमयाद्यज्ञाज्ज्ञानयज्ञः परन्तप । सर्वं कर्माखिलं पार्थ ज्ञाने परिसमाप्यते ॥ ४-३३॥ (Bhag. Gita. 4.33)</blockquote>Superior is Jnana yajna above Yajnas involving material offerings. All karmas (actions) in their entirety, O Partha, culminate in Knowledge (jnana).<ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Further, karma, by removing all obstacles and sins, prepare the ground for the attainment of knowledge. Yogavasishta, describes a clear distinction between the stage of choosing actions for moral excellence (primacy of will) and another stage surpassing the moral realms (transcendence). <blockquote>शुभाशुभाभ्यां मार्गाभ्यां वहन्ती वासनासरित् । पौरुषेण प्रयत्नेन योजनीया शुभे पथि ।। ३० | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | अशुभेषु समाविष्टं शुभेष्वेवावतारय । स्वं मनः पुरुषार्थेन बलेन बलिनां वर ।। ३१ (Yoga. Vasi. 2.9.30-31)<ref>Yogavashistam, Mumukshu-vyavahara prakarana ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A0%E0%A4%83/%E0%A4%AA%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%A3%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%8D_%E0%A5%A8_(%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B7%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%B5%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%B9%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%AA%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%A3%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%8D)/%E0%A4%B8%E0%A4%B0%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%97%E0%A4%83_%E0%A5%A6%E0%A5%AF Prakarana 2 Sarga 9])</ref></blockquote>Summary: The stream of desires (vasanas) flows along two courses, good and bad; through strong human efforts, it should be directed along the good course. When the mind is bent upon evil desires, O Mighty among the mightiest, you should keep it engaged in good and holy ones through effort of will.<ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | These couplets indicate the stage of preparation where moral excellence is strongly emphasised, and where the constant performance of holy deeds and the constant meditation of holy thoughts, purity of both body and mind, are urged to be absolutely essential. The prescribed good actions have to be performed mainly to divert the mind from evil as well as purifying it, ridding it of impurities and anxieties preparing it to rise above all desires (including the good desires).<ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | + | A daily routine consisting of physical activities (in the form of Yoga), followed by worship, prayer, reading the shastras etc., is followed merely because it is the prescribed by the shastras. Being a novice a Sadhaka does not fully grasp the spirit of these practices, but as the practice continues, they become pleasant and gets naturally attracted to the object of worship. Worship and the prescribed service become works of love, as they mean more than anything to the sadhaka at this stage. The stage of karma next gives place to the stage of bhakti or devotion, where a spontaneous and natural attraction for the object of worship characterizes the mental attitude of the Sadhaka. Thus, progress and development of every sort depends upon the harmonious working of both the active (karma) and the contemplative (jnana) aspects of the human nature. <ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | So long as the Sadhaka does not attain the aparoksanubhuti (the direct realisation of the self), all actions proceed from him as the subject and the agent; but as soon as the real nature (svarupa) of the self is directly realised, action ceases to proceed from him. It is not to be apprehended, however, that all bodily movements must cease as soon as desires cease, such a Jnani performs karma (prarabdha) without having attachment to its fruits. Neither are the operations of the bodily organs such as eyes, ears etc., nor the mental operations blocked from performing their karma in such a Jnani. He becomes a [[Jivanmukta (जीवन्मुक्तः)|jivanmukta]]. Actions of a jivanmukta do not proceed from will or desire (kamasamkalpavarjita), but they come out spontaneously.<ref name=":1" /> | |

| − | + | ===Jnana Marga - Atmopasana, Aparokshanubhuti and Ananda=== | |

| − | + | The Jnanamarga leads the sadhaka directly to the Absolute (Brahman). The short cut, the straight way, is always found to be much more strenuous and difficult than the long, roundabout ways. The objective of life is to experience the ultimate ontological truth - Self is Brahman - and the way to pursue it is through vairagya (renunciation) captured by the attributes of knowledge (Sadhana by Jnana-marga) is presented in the thirteenth adhyaya of Bhagavadgita. In other words, epistemology or the Indian theory of knowledge is to be able to live and experience the ontological belief that Brahman is in everything in the universe, and it is practiced through a meticulous lifestyle filled with positivity.<ref name=":6">Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) ''Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita.'' New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 170-171)</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Jnanamarga, according to Advaita, advocates atmopasana (worship of ''self or atman)'' with no distinction between the worshipper (subject) and worshipped (object)''.'' In other forms of Sadhana, the deity (Vishnu, Shiva, Devi etc.,) is realized as an object, something different from the subject''.'' The experience of the ''self'' or Absolute is of the nature of aparoksha-anubhuti, the most direct and intimate, clearest, fullest experience that is boundless. It is the source of infinite joy and happiness, with a fullness of feeling, an ecstatic state described as anandam. This aparoksha-anubhuti superior to any other experience is characterized with anandam and has been identified with mukti or freedom from bondage. Yoga techniques of such as meditation and concentration lead to absorption (samadhi) and results in prajna (intuition). Here the subject raises to the level of object which then is completely and faithfully revealed.<ref>Brahma, Nalinīkānta. ''Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā.'' United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Pages 137 - )</ref> | |

| − | + | At a certain stage in the course of Sadhana in Jnanamarga, retirement from active life is indeed prescribed and recommended for the Sadhaka. This is known as the stage of vividisa-sannyasa. When the Sadhaka has reached the stage of dhyana or nididhyasana, i.e. when he finds that meditation has become spontaneous with him and he feels pleasure in withdrawing from the external world and retiring within, then, a Sadhaka is advised not to engage himself in any outward action, as it may interfere with the natural and easy flow of his meditation and retard his progress. In Shrimad Bhagavadgita the psychosocial nature of a Yogi in the path of knowledge is described.<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>योगी युञ्जीत सततमात्मानं रहसि स्थितः । एकाकी यतचित्तात्मा निराशीरपरिग्रहः ॥ ६-१०॥ (Bhag. Gita. 6.10)</blockquote>One who is established in meditation should steady his mind, concentrate on the inner ''self'' (retiring within himself), remain in a solitary place all alone (away from the external world), controlling his thought and mind, free from desire and sense of possession. | |

| − | + | Shrimad Bhagavadgita presents the all positive psychological elements or characteristics that everyone needs to cultivate to be able to learn the knowledge of Brahman. These elements of Jnana include<ref name=":6" /><blockquote>अमानित्वमदम्भित्वमहिंसा क्षान्तिरार्जवम् । आचार्योपासनं शौचं स्थैर्यमात्मविनिग्रहः ॥ १३-८॥ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Bhagavadgita presents the all positive psychological elements or characteristics that everyone needs to cultivate to be able to learn the knowledge of Brahman. These elements of Jnana include<ref name=":6" /><blockquote>अमानित्वमदम्भित्वमहिंसा क्षान्तिरार्जवम् । आचार्योपासनं शौचं स्थैर्यमात्मविनिग्रहः ॥ १३-८॥ | ||

इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यमनहङ्कार एव च । जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ १३-९॥ | इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यमनहङ्कार एव च । जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ १३-९॥ | ||

| Line 212: | Line 91: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| + | [[Category:Vedanta]] | ||

Revision as of 22:16, 8 December 2022

Sadhana begins with the consciousness of the existence of some Supreme Power, an intimate connection or rather a conscious union with which is deemed absolutely essential to the realization of the summum bonum of life.[1]

This Supreme Power has sometimes been regarded as the Higher Self of man himself and not any foreign power with whom only an external connection could possibly be established. Sadhana, thus means the conscious effort at unfolding the latent possibilities of the individual self and is hence limited to human beings alone. Only in man a special equipment, viz., a conscious effort apparently separate from the activities of nature, comes into being.[1]

Indian psychology, is a system of psychology that is rooted in classical Indian thought and is implied in numerous techniques prevalent in the subcontinent for psycho-spiritual development such as the various forms of yoga.

Opposing Social and Spiritual Dimensions

While understanding the Indian concept of Self, it was studied that the expansion of self happens in two directions. When the manas or mind turns outwards and in association with sense-organs, driven by desires (sankalpas) and attachments (mamakara), there is an explosive growth of social self. Thus, the physical self gets integrated with the social self in the social system. Jiva gets entangled in various aspects of social identities such as varna, ashrama, national and regional identities. Besides these there are other elements of self that get added to the identity box as one advances in career, and acquire wealth, a house, special equipment and professional success. A person gets caught in the web of kama, krodha, lobha, moha, mada and matsara, (arishadvargas or six enemies) which alter his psychological make-up. Indulgences to gratify various needs, further draws a person towards the ego-enhancing objects and luxuries. All these lead to an endless, perhaps infinite, growth in our social self.[2]

When one stops worrying about the fruits of one’s efforts, performs one’s duties by controlling the senses with the manas, and allows the karma-indriyas to perform their tasks without any anxiety, then slowly one begins to withdraw from the hustle and bustle of the world and begins to be inner centered. Thus, the social self starts to lose its meaning for the person, for it is an external identity, and the person begins to be anchored inside, on the inner self, following this path. In this journey towards the self (atman), the physical self and social self start to slowly melt, and when the intellect of the person becomes stable, then one realizes the Atman or the real self.

प्रजहाति यदा कामान्सर्वान्पार्थ मनोगतान् । आत्मन्येवात्मना तुष्टः स्थितप्रज्ञस्तदोच्यते ॥ २-५५॥ (Bhag. Gita. 2.55)

Meaning: When a man completely casts off, O Partha, all the desires of the mind, and is satisfied in the (inner) self by the self (mind), then is he said to be one of steady wisdom.

This melting of the self is just the opposite of the explosive growth of the social self.[3] Thus, the Indian concept of self expands to be infinite socially and contracts socially for the true self to expand to be infinite metaphysically. This conceptualization of the self is critical to the understanding of psychological processes in the Indian cultural context.[2]

Role of Psychological Self in Sadhana

The Self (defining which is based on the sampradaya) is not ordinarily realized by us because of its extreme fineness and minuteness. The Buddhi is to acquire microscopic vision (drsyate tvagryaya buddhya) through repeated acts of concentration if it is to have an intuition of the Self. The whole aim of Sadhana in the Indian traditions with its innumerable details (which seem very often useless and unmeaning) is to gradually educate the mind towards concentration. It enjoins rigid discipline, scrutiny in every action (from waking up in the morning till retiring in the night) and emphasizes upon minute and detailed regulation of life. It may appear meaningless or even absurd to many, however, such practices offer the required training to a novice whose mind takes interest in everything presented to it and diffuses its energy. It should be noted that many disciplinary practices are not enjoined for all, there are exemptions based on many factors including the capacities of different individuals. Shruti emphasized that the real Self can be attained through the mind and mind alone.

मनसैवानुद्रष्टव्यं नेह नानास्ति किं चन । मृत्योः स मृत्युमाप्नोति य इह नानेव पश्यति। बृह. ४,४.१९ ॥ (Brhd. Upan. 4.4.19)

This Brahman must be realized by the mind alone after steady and constant reflection. In Brahman that is to be realized, there is no duality or diversity. He who sees here, as though it were many, goes from death to death (attains the cycles of samsara).[4]

The inwardly directed individual self perceives vaguely its latent infinitude and realizes gradually that its limitation and bondage are not inherent in its nature but are rather imposed on it, and wants somehow to shake them off and thus realise its full autonomy. Liberation or vimukti is identical with freedom, and freedom is expansion. It is the gross outward matter and contact with matter that have made the self appear limited. The deeper and deeper one dives into self, the more of expansion, freedom and light does one feel and enjoy. This conscious urge of the finite to become more and more, expands till it realizes its infinitude - is what is really meant by mumukshutva (desire for liberation) which forms the unmistakable first step in the course of, Sadhana.[1]

The course of discipline or Sadhana strengthens the finite consciousness step after step and gradually unfolds the infinitude that was all along latent in the same. Sadhana, is completed when no foreign element, no matter, no ‘other,’ remains as an unresolved contradiction or opposition, and when the self has established its sovereignty not by opposing itself to matter, but by resolving matter completely unto itself.[5]

Paths of Sadhana

Sadhana can be performed in different ways and as such broadly it involves either or both of the two paths - mental or physical, but the eventual change it brings about is in psychological status of the sadhaka. The value of the different forms of Sadhana are best understood, if we consider the respective contributions of each, Karma, Bhakti and Jnana, towards the development of the Sadhaka for the attainment of his goal. They are not to be regarded strictly as independent forms of Sadhana in the sense that only one of them is sufficient for the attainment of the goal. These three are intimately connected with one another, and the co-operation of all of them is necessary for the realisation of the ideal. Modern Psychology no longer believes in the compartmental division of the Faculty Psychologists, but firmly establishes the inter-connection of the various aspects of the mind. Over-emphasis or undue focus on only one aspect eclipses or paralyzes the mind of a sadhaka, and is best avoided. The keyword is achieving moderation or balance and the best path is usually very personal based on the sadhaka's temperaments, his/her personal merits and deficiencies where improvement is required to achieve the goal. This working in moderation is also emphasized in the Gita where we find Yoga described as ‘samatvam’ (balance). The natural bent or aptitude determines the particular line of Sadhana for every particular Sadhaka, but it is never to be forgotten that the particular line is merely an occasion or the main support for the development of all the different aspects.[6]

According to Dr. Nalinikanta Brahma, Karma, Bhakti and Jnana may be regarded as disciplines suiting three different stages in the course of development of the Sadhaka. All controversy arises when this aspect of mutual co-operation is lost sight of, and undue importance or unmerited neglect is accorded to one or other of these aspects. Shrimad Bhagavata Purana, mentions that for a Sadhaka,

तावत् कर्माणि कुर्वीत न निर्विद्येत यावता । मत्कथाश्रवणादौ वा श्रद्धा यावन्न जायते ॥ ९ ॥ (Bhag. Pura. 11.20.9)

Karma has to be performed until one does not feel dissatisfied (towards it) and after attaining a faith by listening to the divine stories etc., (either for bhakti or jnana), all karmas should be renounced.[6]

Karma has very often been downplayed by the advocates of jnana and bhakti. Karma (specifically those proceeding from desires) and jnana are incompatibles, declare the advocates of Jnana-marga, as one is the result of ignorance (avidya) and the other involves true knowledge (vidya).

Karma Marga - Attainment of purification of sharira and manas

The earliest form of Sadhana advocated by the Vedas is Karma. In this path of sadhana we may note different routes taken by various texts.

- Karmas which include the Vaidika yajnas (dravya-yajnas), vidhis to propitiate the deities (Mimamsa), upasanas (mental processes), tantra etc., to attain results such as residence in the higher worlds, but not freedom (moksha).

- Ashtanga-yoga system includes regulation of physical and physiological (bodily) processes to control the vrittis of the manas.

- Tantras lay special emphasis on the process to control the Shat-chakras and Sushumna nadi for spiritual progress. It also combines elements of yoga, worship, prayer and meditation for purification.

In this path of sadhana, physical actions are performed (including daily worship, chores and ritualistic acts) such that they ultimately lead to a state of desirelessness. Of the six astika darshanas, Purva Mimamsa, founded by Maharshi Jaimini, is engaged with Karma, mainly with respect to the various yajnas. Such rites and ceremonies advocated in this darshana shastra are limited in that they grant the performer (yajamana) a place of residence in swargaloka but are incompetent to award moksha.

The Puranas and Smrtis use the term to mean such actions as daily worship (sandhya etc.), fixed religious observances, fastings, etc., and divide all such karmas into three groups, viz., nitya, naimittika, and kamya based on the periodicity and goal of such actions. Such mental processes as meditation and reflection (dhyana and vichara) are generally excluded from the province of Karma by the Vedantists. Almost all the Vedantic thinkers, however, agree in holding that only nitya karmas are useful towards jnana (by removing obstacles), kamya karmas being always excluded as they give rise to karmaphala that become positive hinderence to jnana.[6]

The Sadhaka has to begin with karma, that being perfectly suitable to the beginner who is not yet purified in body and mind. It is karma that purifies the mind of the Sadhaka and makes him fit for the acquisition of higher truths. Adishankaracharya stresses that

अपेक्षते च विद्या सर्वाण्याश्रमकर्माणि नात्यन्तमनपेक्षैव। ...उत्पन्ना हि विद्या फलसिद्धिं प्रति न किंचिदन्यदपेक्षते उत्पत्तिं प्रति तु अपेक्षते (Shankara Bhashya on Brahma Sutras 3.4.26)

All karmas (yajnas and related rituals) are useful for origination of knowledge. Even the scriptures prescribe them as they serve an indirect means to the attainment of knowledge.[7] There is incompatibility of jnana and karma only when jnana had been reached and not before that stage. That each jnana and karma margas have their own place in a Sadhaka's life, is reinforced in Shrimad Bhagavadgita

श्रेयान्द्रव्यमयाद्यज्ञाज्ज्ञानयज्ञः परन्तप । सर्वं कर्माखिलं पार्थ ज्ञाने परिसमाप्यते ॥ ४-३३॥ (Bhag. Gita. 4.33)

Superior is Jnana yajna above Yajnas involving material offerings. All karmas (actions) in their entirety, O Partha, culminate in Knowledge (jnana).[6] Further, karma, by removing all obstacles and sins, prepare the ground for the attainment of knowledge. Yogavasishta, describes a clear distinction between the stage of choosing actions for moral excellence (primacy of will) and another stage surpassing the moral realms (transcendence).

शुभाशुभाभ्यां मार्गाभ्यां वहन्ती वासनासरित् । पौरुषेण प्रयत्नेन योजनीया शुभे पथि ।। ३० अशुभेषु समाविष्टं शुभेष्वेवावतारय । स्वं मनः पुरुषार्थेन बलेन बलिनां वर ।। ३१ (Yoga. Vasi. 2.9.30-31)[8]

Summary: The stream of desires (vasanas) flows along two courses, good and bad; through strong human efforts, it should be directed along the good course. When the mind is bent upon evil desires, O Mighty among the mightiest, you should keep it engaged in good and holy ones through effort of will.[6]

These couplets indicate the stage of preparation where moral excellence is strongly emphasised, and where the constant performance of holy deeds and the constant meditation of holy thoughts, purity of both body and mind, are urged to be absolutely essential. The prescribed good actions have to be performed mainly to divert the mind from evil as well as purifying it, ridding it of impurities and anxieties preparing it to rise above all desires (including the good desires).[6]

A daily routine consisting of physical activities (in the form of Yoga), followed by worship, prayer, reading the shastras etc., is followed merely because it is the prescribed by the shastras. Being a novice a Sadhaka does not fully grasp the spirit of these practices, but as the practice continues, they become pleasant and gets naturally attracted to the object of worship. Worship and the prescribed service become works of love, as they mean more than anything to the sadhaka at this stage. The stage of karma next gives place to the stage of bhakti or devotion, where a spontaneous and natural attraction for the object of worship characterizes the mental attitude of the Sadhaka. Thus, progress and development of every sort depends upon the harmonious working of both the active (karma) and the contemplative (jnana) aspects of the human nature. [6]

So long as the Sadhaka does not attain the aparoksanubhuti (the direct realisation of the self), all actions proceed from him as the subject and the agent; but as soon as the real nature (svarupa) of the self is directly realised, action ceases to proceed from him. It is not to be apprehended, however, that all bodily movements must cease as soon as desires cease, such a Jnani performs karma (prarabdha) without having attachment to its fruits. Neither are the operations of the bodily organs such as eyes, ears etc., nor the mental operations blocked from performing their karma in such a Jnani. He becomes a jivanmukta. Actions of a jivanmukta do not proceed from will or desire (kamasamkalpavarjita), but they come out spontaneously.[6]

Jnana Marga - Atmopasana, Aparokshanubhuti and Ananda

The Jnanamarga leads the sadhaka directly to the Absolute (Brahman). The short cut, the straight way, is always found to be much more strenuous and difficult than the long, roundabout ways. The objective of life is to experience the ultimate ontological truth - Self is Brahman - and the way to pursue it is through vairagya (renunciation) captured by the attributes of knowledge (Sadhana by Jnana-marga) is presented in the thirteenth adhyaya of Bhagavadgita. In other words, epistemology or the Indian theory of knowledge is to be able to live and experience the ontological belief that Brahman is in everything in the universe, and it is practiced through a meticulous lifestyle filled with positivity.[9]

Jnanamarga, according to Advaita, advocates atmopasana (worship of self or atman) with no distinction between the worshipper (subject) and worshipped (object). In other forms of Sadhana, the deity (Vishnu, Shiva, Devi etc.,) is realized as an object, something different from the subject. The experience of the self or Absolute is of the nature of aparoksha-anubhuti, the most direct and intimate, clearest, fullest experience that is boundless. It is the source of infinite joy and happiness, with a fullness of feeling, an ecstatic state described as anandam. This aparoksha-anubhuti superior to any other experience is characterized with anandam and has been identified with mukti or freedom from bondage. Yoga techniques of such as meditation and concentration lead to absorption (samadhi) and results in prajna (intuition). Here the subject raises to the level of object which then is completely and faithfully revealed.[10]

At a certain stage in the course of Sadhana in Jnanamarga, retirement from active life is indeed prescribed and recommended for the Sadhaka. This is known as the stage of vividisa-sannyasa. When the Sadhaka has reached the stage of dhyana or nididhyasana, i.e. when he finds that meditation has become spontaneous with him and he feels pleasure in withdrawing from the external world and retiring within, then, a Sadhaka is advised not to engage himself in any outward action, as it may interfere with the natural and easy flow of his meditation and retard his progress. In Shrimad Bhagavadgita the psychosocial nature of a Yogi in the path of knowledge is described.[6]

योगी युञ्जीत सततमात्मानं रहसि स्थितः । एकाकी यतचित्तात्मा निराशीरपरिग्रहः ॥ ६-१०॥ (Bhag. Gita. 6.10)

One who is established in meditation should steady his mind, concentrate on the inner self (retiring within himself), remain in a solitary place all alone (away from the external world), controlling his thought and mind, free from desire and sense of possession. Shrimad Bhagavadgita presents the all positive psychological elements or characteristics that everyone needs to cultivate to be able to learn the knowledge of Brahman. These elements of Jnana include[9]

अमानित्वमदम्भित्वमहिंसा क्षान्तिरार्जवम् । आचार्योपासनं शौचं स्थैर्यमात्मविनिग्रहः ॥ १३-८॥

इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यमनहङ्कार एव च । जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ १३-९॥

असक्तिरनभिष्वङ्गः पुत्रदारगृहादिषु । नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ १३-१०॥

मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी । विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ १३-११॥

अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वं तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् । एतज्ज्ञानमिति प्रोक्तमज्ञानं यदतोऽन्यथा ॥ १३-१२॥ Bhaga. Gita. 13. 8-12)

Shri Krishna lists that the characteristics mentioned (in these shlokas) constitute Jnana and those opposite to these are termed as Ajnana.[9]

- अमानित्वम् ॥ humility

- अदम्भित्वम् ॥ pridelessness

- अहिंसा ॥ nonviolence

- क्षान्तिः ॥ tolerance

- आर्जवम् ॥ simplicity

- आचार्योपासनम् ॥ service to a spiritual teacher

- शौचम् ॥ cleanliness

- स्थैर्यम् ॥ steadfastness

- आत्मविनिग्रहः ॥ self-control

- इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यम् ॥ desirelessness in the sense pleasures

- अनहङ्कारः ॥ without ego

- जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ remembering the problems of birth, death, old age, disease, and miseries that go with the physical body (to motivate oneself to think about the Atman)

- असक्तिः ॥ without attachment

- पुत्रदारगृहादिषु अनभिष्वङ्गः ॥ without fondness towards son, wife, or home etc.

- नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ constancy in a balanced manas or citta (or mind) or having equanimity of the mind in attainment of favorable or unfavorable consequences

- विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ preferring solitude having no desire to associate with people

- मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी ॥ unwavering offering of unalloyed devotion to kRSNa

- अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वम् ॥ Constant dwelling on the knowledge pertaining to the Self

- तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् ॥ Contemplation (on the goal) for the attainment of knowledge of the truth

Bhakti Marga

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 61-75)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 65 - 91)

- ↑ Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 103-104)

- ↑ Dr. N. S. Ananta Rangacharya (2004) Prinicipal Upanishads, Volume 3, Brhdaranyakopanishat. Text, English Translation and Brief notes according to Sri Ranga Ramanujamuni. Bangalore: Sri Rama Printers (Pages 311)

- ↑ Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 46-48)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Pages 91- 116)

- ↑ Brahmasutras by Swami Sivananda (Shankaracharya's Bhashyam on सर्वापेक्षा च यज्ञादिश्रुतेर् अश्ववत् । ( ब्रसू-३,४.२६ । )

- ↑ Yogavashistam, Mumukshu-vyavahara prakarana (Prakarana 2 Sarga 9)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 170-171)

- ↑ Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Pages 137 - )