Sadhana and Indian Psychology (साधनं मनोविज्ञानं च)

Sadhana begins with the consciousness of the existence of some Supreme Power, an intimate connection or rather a conscious union with which is deemed absolutely essential to the realization of the summum bonum of life.[1]

This Supreme Power has sometimes been regarded as the Higher Self of man himself and not any foreign power with whom only an external connection could possibly be established. Sadhana, thus means the conscious effort at unfolding the latent possibilities of the individual self and is hence limited to human beings alone. Only in man a special equipment, viz. a conscious effort apparently separate from the activities of nature, comes into being.[1]

Indian psychology, is a system of psychology that is rooted in classical Indian thought and is implied in numerous techniques prevalent in the subcontinent for psycho-spiritual development such as the various forms of yoga.

Indian Concept of Self

“What is the self?” In traditional Western terminology, such questions belong to ontology, a study concerning the nature of reality. Epistemologically, it raises issues concerning the nature of knowledge. A third type of issue concerns the questions related to personal identity. For some, as for Locke, personal identity matters in the ethicolegal sphere, since only the same person that committed the alleged crime may be punished for it, not someone else. For some others, it is a deeply existential issue; finding the correct answer to the question “who am I?” is deemed extremely important, for a wrong answer would make a person imposter - living someone else’s life, as it were. The identity issue thus involves consideration of justice and value, and thus belongs to ethics or axiology as well.[2]

The problem of identity thus concerns ontology, epistemology, and ethics, three major branches that comprise most of philosophy as it is conceived of in the Western tradition. In addition, the question, “Who am I?” is directly concerned with both - the philosophical inquiry about nature of selfhood and with practical issues concerning social and personal identity. Answers to this question have profound social and existential implications.

There have been endless controversies in the Indian as well as Western traditions on the putative existence, nature, knowledge, and value of whatever that has been called the self. The problem of identity thus relates to the most profound personal and ideological dilemmas. As such, the discovery of one’s true selfhood becomes a most crucial issue in life.

“Know thyself” was a most important exhortation in ancient Greece. Similarly, in ancient India, Yajnavalkya exhorted that the Self ought to be the subject to know about and mediate upon. The self continues to be an important topic of inquiry to many philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, anthropologists, as well countless other persons of varied backgrounds.[2]

Defining Self - Western Tradition

Allport (1943) identified the following different meanings that the term ego had acquired by the time of his writing: the self as[2]

- a knower,

- an object of knowledge

- primitive selfishness

- dominance drive

- passive organization of mental processes

- a “fighter for ends”

- a behavioral system

- a subjective organization of culture.

About a decade later, Allport (1955) critically considered seven more concepts closely related to self and ego: the bodily sense, self-identity, ego enhancement, ego extension, rational agent, self-image, and propriate striving. He also mentioned yet another definition of the self, suggested by P. A. Bertocci (1945), as a “knower, thinker, feeler, and doer - all in one blended unit of a sort that guarantees the continuance of all becoming.” Interestingly, this definition of the self is an almost exact translation of the Upanishadic view of the person as one who knows, feels, and acts (jñata, bhokta, karta).[2] Hume affirmed that the mind was "nothing but a bundle

Seminal contributions in defining selfhood came from the works of William James, C. H. Cooley, G. H. Mead, and Freud, whose ideas have continued to the revival in psychological studies of selfhood and related topics. Many other Enlightenment thinkers such as David Hume, Leibniz, Descartes, Immanuel Kant, Skinner and later on Erik Erikson, Jean Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg to name a few, denied or affirmed the existence of Self and proposed modern theories about self and knowledge. In the present article only those western perspectives which are similar to the Upanishadic concepts have been discussed as they pertain to the scope of the topic.[2]

Defining Self - Indian Tradition

Many Indian and Western scholars, in the recent decades have studied and presented the concept of Self based on Indian perspectives given in the Vedas, varna and ashrama dharmas, samskaras, in the philosophical texts such as the shad-darshanas, the Brahmasutras, the Upanishads, the Itihasas, the Puranas, and Tantras etc., all of which influence the Indian psychological make-up.[3]

In Kathopanishad, the nature of Self is summarized by Yama as the eternal principle in person that never changes.[4]

"This principle, Yama says, is tinier than the atom and larger than the largest of things, it is the One underlying the Many, the Permanent (nitya) behind the Ephemeral (anitya) in the entire universe. It cannot be divided or destroyed; the Self is not killed by the destruction of the body. It is by knowing the changeless Self behind all the changes that one attains immortality."

A few important Upanishadic references dealing with the two central topics of inquiry: the nature of the Self and the nature of reality as a whole, are mentioned below.[4]

- Yajnavalkya Maitreyi Samvada in Brhdaranyaka Upanishad (2.3.1-14; 4.5.1-15) which is the dialogue about the nature of Self.

- Svetashvatara Upanishad where the nature of self and reality, the origin of the world, Brahman etc., are discussed. Self is referred to as an enjoyer and sufferer in life (bhokta).

- Yama Nachiketa Samvada in Kathopanishad where the nature of self is described. Self is experienced when, through the practice of Yoga, the five senses are held back, the mind is undistracted, and the intellect is stabilized.

- Taittriya Upanishad (2.1) describes that the Brahman is to be attained through the realization of the Self as the Truth (satyam), Knowledge (jñanam), and Infinite (anantam). It further describes the nature of self as consisting of Ananda (Tait. Upan. 2.5).

- Mandukya Upanishad (12 mantras) declares that self is identical with the Brahman. It describes the mode of knowing self, and distinguishing the various states of consciousness viz., wakeful state, dream state, deep sleep state, turiya or fourth state.

It is significant to note that the Self affirmed by the Upanishads is derived from the fourth state of consciousness, the like of which is not usually recognized either by contemporary psychology or by the empiricist or rationalist epistemologies shaped by the Enlightenment thinkers. This is where we can see some of the deepest differences between the Indian and Western epistemologies in general, and psychologies in particular.[4]

Although the Upanishads were concerned with overcoming suffering, they were not motivated by the concern to avoid damnation on the Day of Judgment, as was Descartes. Unlike Descartes, whose “meditations” essentially displayed an exercise of the power of reasoning, the Upanishadic quest was fundamentally contemplative. Indeed, the Upanishads inspired a psychology and a view of consciousness radically different from Western psychology in the shadow of Descartes. By and large, Western psychology has neglected the evidence of the altered and “higher” states of consciousness. The primary reason for such neglect is that the so-called “higher” states attainable through various forms of meditation or contemplation have been considered “mystical,” a term which has unfortunately acquired several pejorative connotations, such as mysterious, irrational, and dangerous. What the Upanishads offer is not simply a doctrinaire affirmation of the Self, plus some verbal pointers to an essentially indescribable Self; they also offer a clear account of what would be attained through the experience of the Self, and suggest specific ways to get it.[4]

Of the six darshana shastras, the Vedanta is the strongest supporter of the doctrine of the Self. The Sankhya and Yoga also affirm a permanent Self.

Terminology of Consciousness and Self

In many texts we find the two related terms “consciousness” and “self” used and expressed in various ways. In this section, the two concepts are clarified, the different senses they convey and their notations are discussed.[5]

- Self (with a capital "S") at the universal level: Absolute and universal (as Brahman in Advaita). The Upanishadic conception of the Brahman is that it is Consciousness and Supreme Self at the same time. Consciousness and Self are considered in their most abstract and universal form.

- self (with a lower case "s" and italicized) at an individual level: consciousness as-such, at the level of the individual - without having the role of an agent (as purusha in Samkhya-Yoga), - in the role of a witness (as atman or sakshin in Vedanta).

- self (with a lower case "s") at the bodily level: A person who wills, acts and feels, the Jīva (empirical self) in Advaita. Jiva is embodied consciousness, whereas jiva-sākṣin (as in self) is the witnessing consciousness. We may also use “self” in a general nonspecific sense to refer to self at all its levels, where a distinction is not warranted.

Jiva - A Composite of Sharira, Manas and Atman

A human being is not merely confined to the appearance it projects, that is, the physical contours and aspects of the body. It is a collection of three bodies (sthula, sukshma and karana shariras) encompassing the gross elements to the subtle layers of the mind that act as encasements for the true Self. The Taittiriya Upanishad presents the Vedic conceptualization of the mind-body complex, i.e., jiva.[6]

Indian psychology involves the study of the Jiva (जीवः) referred to in Vedanta, as a composite human being. Jīva, which literally means a living being, is often used in Indian thought as a technical term that is the closest to what is called “person” in contemporary psychology. As per Vedanta, a jiva is conceived as a multilayered entity, consisting of body (Sharira), mind (Manas), and consciousness (Atman). Jiva is the knower (jñātā), enjoyer/sufferer (bhoktā), and agent of action (kartā). Ayurveda texts present a similar definition of a person. With regard to their role in psychological aspects, we have the following activities for each of the layers of the Jiva.[7]

- Body refers to the nervous system, the senses (Indriyas), and associated structures connected with the brain. Body is the source of natural appetites, which translate themselves into desires, urges, cravings, and longings in the mind.

- Mind (manas) is the hypothetical cognitive instrument related to the body at one end and consciousness at the other.

- Consciousness is conceived to be irreducibly distinct from body and mind. It constitutes the nonphysical aspect of the person. It is the source of subjectivity and the very base of one’s experience of being, knowing, and feeling.

From the functional point of view a person functions at three different levels using the above three parts of the composite.[7]

- A person is capable of processing information from the sense-organs through the instrumentalities of the body. This may be called the level of observation. Thus the sense organs are data collection points situated in the gross aspect of Jiva, namely the body.

- A person is capable of thinking, feeling and acting based on the mind's processing of information received from the sense-organs. This level of understanding is facilitated by the functioning of the mind. The mind is the data processor situated in the subtle aspect of Jiva.

- A person's mental faculties after appropriate sadhana, participate with the consciousness as-such (the Atman) relatively, if not absolutely, free from the bodily processes or their influence. This level is transcognitive realization of truth. In such a state, a person experiences the consciousness as-such, becomes aware of the truth self, and of what is real.

The concepts of shravana (literally hearing, but can be equated with observation in general), manana (thinking/understanding), and nididhyasana (meditative realization) roughly correspond to the three levels of knowing. At the level of shravana and manana, observations and understanding, there is a basic distinction between subject and object and thought and action. Knowing and being are dissociated. In meditative realization, a state achieved by nidhidhyasana, the distinction between subject and object disappears; thought and action, knowing and being blend into each other.[7]

Body, mind, and consciousness are not only conceptually distinct, but are also mutually irreducible in the human context. Consciousness is qualitatively different from the body and the mind with which it may be associated. For this reason, though it is associated with a mind at a given time, it does not interact with it. The body and the mind, unlike consciousness, are physical; and they can interact with each other and are influenced by each other. However, it is important to note that a mind cannot be reduced into its physical constituents and a body cannot be transformed into a mind even though they influence each other within a person. They function differently. From this perspective, the body is conceived as gross matter that permits disintegration. However, mind being a subtle form of matter is not constrained by spatiotemporal variables in the same manner as the gross body does. The body disintegrates irretrievably at death. The mind, however, has the potential to survive bodily death.[7]

Metaphysical and Physical Self

In previous section we saw how the Jīva or the person, is a unique composite of consciousness, mind, and body. A review of the study of self in India reveals that indeed the core of Indian self is metaphysical, and it has been the focus of study by philosophers as well as psychologists. Thus we find a general agreement that the metaphysical self, Atman, is the real Self and it is embodied in a biological or physical body of the composite Jiva (जीवः). This core distinction of Jiva from a mere human body is reflected in the treatment methods adopted in Ayurveda unlike those in modern medicine where a person is limited to a physical self.[7][3]

The unity of the person, despite constantly changing mental states and bodily conditions, is a function of the presence/reflection of Atman (consciousness as-such). Here a distinction needs to be made between consciousnesses as-such identified as Brahman, Atman, or Purusha, and awareness. Consciousness as-such is unchanging and ineffable. It is indeterminate and unqualified, and as such it takes no forms. In the context of cognitive activity, its role is no more than to reflect/illumine the form the mind takes in its interaction with the world through the sensory gateways. Awareness is the result of consciousness illuminating the forms the mind takes. The person whose mind acts through the bodily apparatus may be considered conditioned because of thought, passion, and action are biased and distorted by the conditions of the body. Only an unconditioned person can have the true reflections of consciousness as-such. The goal of the person is to reach such an unconditioned state.[7]

Psychological Self

Beyond the physical self exist psychological self and social self, and both these concepts are brimming with cultural constructions. For example, the varna system is an important part of Indian social self, which has relevance for the Indian population and the Indian Diaspora but little relevance for other cultures. The manas or mind, chitta, buddhi, ahankara etc., form the psychological constructs of the person and are critical in understanding the psyche of Indians.[3]

Social Self

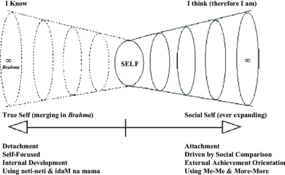

In an attempt to differentiate the Indian concept of social self from that of the people in the West, some cross-cultural psychologists have shown that Indians have both independent and interdependent selves and are both individualistic and collectivist in their cognition. (Bhawuk page 90)

The metaphysical self, Atman is embodied in a biological or physical self, and through the varna system right at birth, the biological self acquires a social Self. With changing times though there is little adherence to the ashrama system on a mass scale, the idea and social construct still persists. With advancing age it is still not unusual for people to start slowing down on their worldly commitments and pass on the baton to the next generation.[3] There are many factors (social, economic, cultural, regional, ecological) that contribute towards the social self construct of person.

- Varna System

- Ashrama System

- Spiritual identity

- Regional identity

Depending on which phase of life one is in, the self is viewed differently. Lifestyle completely changes from phase to phase of the ashrama system. For example, as a student one ate less (alpahari), as a grhastha there was no restriction on food, as a vanprastha he ate fruits and roots and as a sanyasi he begged for food and ate unconcernedly about taste. Varna and Ashrama dharmas clearly defined one's occupation and role in the society and therefore, the Indian concept of Self is socially constructed and varies with occupation and stage of an Indian.[3]

Spirituality can be seen to permeate the masses in India, and social life revolves around rituals that work as a symbolic reminder that people in this culture value spirituality. Small (e.g., vratas and pujas in a week, a paksha, monthly, annually), and big celebrations (such as the Kumbh Mela which meets every 12 years) mark the Indian lifestyle. Every day is dedicated to a deity and every person can choose a deity of his or her choice to worship. When Atman attains unity with the Supreme Being, brahman, and this realization or anubhuti is the goal of the human being. In that paradigm, when one experiences the real self, one experiences boundlessness or infinite state of supreme being. In other words, much like the social self that has the potential to grow infinitely, the real self has the potential to be limitless. Thus, the Indian concept of self expands to be infinite socially and contracts socially for the true self to expand to be infinite metaphysically. This conceptualization of the self is critical to the understanding of psychological processes in the Indian cultural context.[3]

Study of Self at various Levels

A person (jiva) may be studied from[7]

- a physiological perspective to assess influence of bodily processes on mental states and vice-versa.

- the psychophysical perspectives of the mind to learn its functionality, factors influencing, controlling, and enhancing human potential and wellbeing.

- the psycho-spiritual perspectives derived from the mind-consciousness association to understand and realize about the non-physical resources of human functioning available due to the association of the mind with consciousness as-such.

Thus a person can be studied at various levels; two of which are most highly pertinent to psychology - the psychophysical and psycho-spiritual levels. The various concepts of self, are well grounded in different Indian philosophical and vedantic texts. The metaphysical self is most commonly visualized as Atman, which is situated in a living being as a result of past karma. The physical self can further be classified as sharira-traya (the three bodies - sthula, sukshma and karana shariras) or panchakoshas (constituting - annamaya, pranamaya, manomaya, vijnanamaya and anandamaya koshas). While social self is manifested by the various beings in different ways at different proportions, human beings are believed to be the only ones who can pursue moksha (or liberation) purushartha, enlightenment, jnana (or knowledge), or self-realization.

Panchakosha model of self

Based on the Panchakoshas presented in the Taittriya Upanishad the following classification gives rise to a model of Self having the following elements.[3]

| Self | Kosha | Elements | Functions | Factors Affecting Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metaphysical Self (the I-ness) - Subtlest | Anandamaya Kosha | Jivatma (Atman Embodied) | Kartrtva (doer) and Bhoktrtva (enjoyer) | Sadhana margas

Yoga etc. |

| Psychological Self (Mental and Cognitive faculty) Subtle | Vijnanamaya Kosha | Buddhi (the discriminative decision making faculty) | vijñāna—understanding, knowing, direct cognition, wisdom, intuition and creativity. | Sadhana margas

Yoga etc. |

| Manomaya Kosha | Manas, (the cognitive faculty) Antahkarana

Ahamkara |

understanding,

thoughts, ideas perception, processing the inputs of sense-organs | ||

| Physical Self (Physiological

and Physical faculties) Gross |

Pranamaya Kosha | Physiological functions of the body | Functional aspects of the body such as breathing, excretion, digestion etc. | Material Lifestyle |

| Annamaya Kosha | The physical body made of panchabhutas | Human body and its parts such as, tissues, bones, skin, organs etc. |

Sadhana and The Psychological Self

The inwardly directed individual Self perceives vaguely its latent infinitude and realises gradually that its limitation and bondage are not inherent in its nature but are rather imposed on it, and wants somehow to shake them off and thus realise its full autonomy. Liberation or vimukti is identical with freedom, and freedom is expansion. It is the gross outward matter and contact with matter that have made the Self appear limited. The deeper and deeper we dive into Self, the more of expansion, freedom and light do we feel and enjoy. The conscious urge of the finite to become more and more expanded till it realises its infinitude is what is really meant by mumukshutva (desire for liberation) which forms the unmistakable first step in the course of, Sadhana.[1]

Sadhana Margas

Karma Marga

The earliest form of Sadhana advocated by the Vedas is Karma. Of the six astika darshanas, Purva Mimamsa engaged with the Karma philosophy. The term Karma, however, was used in a limited sense to denote the various yajnas. In a broad sense, it includes all actions, physical and psychical, although it is usually limited to bodily actions.[8]

Jnana Marga

The objective of life is to experience the ultimate ontological truth - Self is Brahman - and the way to pursue it is through vairagya (renunciation) captured by the attributes of knowledge (Sadhana by Jnana-marga) is presented in the thirteenth adhyaya of Bhagavadgita. In other words, epistemology or the Indian theory of knowledge is to be able to live and experience the ontological belief that brahman is in everything in the universe, and it is practiced through a meticulous lifestyle filled with positivity.[9]

Bhagavadgita presents the all positive psychological elements or characteristics that everyone needs to cultivate to be able to learn the knowledge of Brahman. These elements of Jnana include[9]

अमानित्वमदम्भित्वमहिंसा क्षान्तिरार्जवम् । आचार्योपासनं शौचं स्थैर्यमात्मविनिग्रहः ॥ १३-८॥

इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यमनहङ्कार एव च । जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ १३-९॥

असक्तिरनभिष्वङ्गः पुत्रदारगृहादिषु । नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ १३-१०॥

मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी । विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ १३-११॥

अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वं तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् । एतज्ज्ञानमिति प्रोक्तमज्ञानं यदतोऽन्यथा ॥ १३-१२॥ Bhaga. Gita. 13. 8-12)

Shri Krishna lists that the characteristics mentioned (in these shlokas) constitute Jnana and those opposite to these are termed as Ajnana.[9]

- अमानित्वम् ॥ humility

- अदम्भित्वम् ॥ pridelessness

- अहिंसा ॥ nonviolence

- क्षान्तिः ॥ tolerance

- आर्जवम् ॥ simplicity

- आचार्योपासनम् ॥ service to a spiritual teacher

- शौचम् ॥ cleanliness

- स्थैर्यम् ॥ steadfastness

- आत्मविनिग्रहः ॥ self-control

- इन्द्रियार्थेषु वैराग्यम् ॥ desirelessness in the sense pleasures

- अनहङ्कारः ॥ without ego

- जन्ममृत्युजराव्याधिदुःखदोषानुदर्शनम् ॥ remembering the problems of birth, death, old age, disease, and miseries that go with the physical body (to motivate oneself to think about the Atman)

- असक्तिः ॥ without attachment

- पुत्रदारगृहादिषु अनभिष्वङ्गः ॥ without fondness towards son, wife, or home etc.

- नित्यं च समचित्तत्वमिष्टानिष्टोपपत्तिषु ॥ constancy in a balanced manas or citta (or mind) or having equanimity of the mind in attainment of favorable or unfavorable consequences

- विविक्तदेशसेवित्वमरतिर्जनसंसदि ॥ preferring solitude having no desire to associate with people

- मयि चानन्ययोगेन भक्तिरव्यभिचारिणी ॥ unwavering offering of unalloyed devotion to kRSNa

- अध्यात्मज्ञाननित्यत्वम् ॥ Constant dwelling on the knowledge pertaining to the Self

- तत्त्वज्ञानार्थदर्शनम् ॥ Contemplation (on the goal) for the attainment of knowledge of the truth

Bhakti Marga

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Page 61-75)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Paranjpe, A. C. (2006) Self and identity in modern psychology and Indian thought. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Pages 75 - 92)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 65 - )

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Paranjpe, A. C. (2006) Self and identity in modern psychology and Indian thought. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Pages 116 - 122)

- ↑ Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Page 94)

- ↑ Dagar, C and Pandey, A. (2020) Well-Being at Workplace: A Perspective from Traditions of Yoga and Ayurveda. Switzerland: Springer Nature

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Pages 5 - 9)

- ↑ Brahma, Nalinīkānta. Philosophy of Hindu Sādhanā. United Kingdom: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1932. (Pages 91- )

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bhawuk, Dharm. P. S. (2011) Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita. New York, Dordrecht Heidelberg, London: Springer. (Pages 170-171)