Types of Discourse (सम्भाषाप्रकाराः)

Types of Discourse (Samskrit: सम्भाषाप्रकाराः) refers to the different styles of discussion and debate. This article discusses these types of discourses in detail.

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

Shri. Bimal Krishna Matilal ji observes in his work 'The Character of Logic in India' that,

.. The intellectual climate in India was bristling with questions such as: “Is there an atma different from sharira ?”; “Is the world (loka) eternal?”; ”What is the meaning, goal, or purpose of life?”; and, “Is renunciation preferable to enjoyment?” etc. which were of major concern.

As teachers and thinkers argued about such matters, there arose a gradual awareness of the characteristics or patterns of correct, acceptable and sound reasoning. There were also concerns to evolve the norms to distinguish sound reasoning from pseudo-reasoning (hetvabhasa) which is unacceptable.[1]

Gradually, the notions of ‘good’ and acceptable debate took shape as distinct from wrong and ugly arguments. That gave rise to the development of a branch of study dealing with theories of reasoning and logic (Hetu vidya or Hetu shastra). Subsequently, manuals came to be written for conduct of proper and successful debates (Tarka vidya or Vada vidya). These manuals included instructions and learning methods for the guidance of aspiring debaters. The earliest known text of that genre was Tantrayukti (structured argument) compiled to systemize debates conducted in learned councils (Parishads).

Debates and arguments then came to be recognized both as art of logical reasoning (Tarka vidya) and science of causes (Hetu shastra) following the path of a well-disciplined method of inquiry (anvikshiki) testing scriptural knowledge by further scrutiny. Therefore, scholars belonging to various schools of philosophy were imparted training in Tarka vidya: the art and skill of conducting impressive successful debates and disputations (Sambhasha or Vada vidhi) in learned assemblies (Parishads). Their training modules included,

- Methods of presenting arguments as per a logically structured format

- Ways to stoutly defend one's thesis by means of genuine criteria of knowledge (Pramana)

- To attack the opponent’s thesis by means of indirect arguments (Tarka)

- Estimating the strengths and weaknesses of arguments of either side

- Establishing one’s own points while setting aside those of the opponent

They were also trained for handling different types of challenges, such as:

- How to vanquish a person of blazing fame

- How to behave with a senior opponent

- How to handle an aggressive and troublesome opponent

- How to conduct oneself in prestigious Parishads, to influence the flow of debate and to impress the judges and the onlookers etc.[2]

सम्भाषाप्रकाराः ॥ Types of Sambhasha

Two major texts that enlist the various types of discussions/debates are - The Charaka Samhita and The Nyaya Sutras.

चरकसंहिता || Charaka Samhita

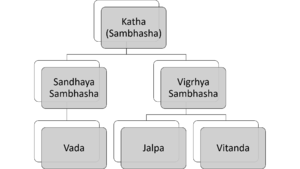

There are 2 types of Sambhasha mentioned in the Charaka Samhita - Sandhaya Sambhasha and Vigrhya Sambhasha[3]

द्विविधा तु खलु तद्विद्यसंभाषा भवति सन्धायसंभाषा विगृह्यसंभाषा च ।[4]

dvividhā tu khalu tadvidyasaṁbhāṣā bhavati sandhāyasaṁbhāṣā vigr̥hyasaṁbhāṣā ca ।

Meaning: Such discussion with the men of the same branch of science is of two kinds - friendly discussion and the discussion of challenge or hostile discussion.[5]

- Sandhaya Sambhasha (friendly discussion) is characterised by

- Participants having scientific knowledge

- Power of argument and counter argument

- Correct knowledge

- Not rejoicing defeat of opponents

- Answering questions with confidence

- Having a polite approach with the opponent[3]

It is said that,

तत्र ज्ञानविज्ञानवचनप्रतिवचनशक्तिसम्पन्नेनाकोपेनानुपस्कृतविद्येनानसूयकेनानुनेयेनानुनयकोविदेन क्लेशक्षमेण प्रियसम्भाषणेन च सह सन्धायसम्भाषा विधीयते ।[4]

tatra jñānavijñānavacanaprativacanaśaktisampannenākopenānupaskr̥tavidyenānasūyakenānuneyenānunayakovidena kleśakṣameṇa priyasambhāṣaṇena ca saha sandhāyasambhāṣā vidhīyate ।

Meaning: The friendly discussion is enjoined with a person who is endowed with knowledge and experience, who is well versed in the dialectics of statement and rejoinder, who does not get angered, possessed of special insight into the subject, who is not carping, who is easily persuaded, who is an adept in the art of persuasion, who has tolerance and pleasantness of speech.[5]

- Vigrhya Sambhasha (hostile discussion) is characterised by examination of the good and bad qualities of the opponent based on which opponents are classified into superior, equal and inferior.[3]

प्रागेव च जल्पाज्जल्पान्तरं परावरान्तरं परिषद्विशेषांश्च सम्यक् परीक्षेत् |...परीक्षमाणस्तु खलु परावरान्तरमिमान् जल्पकगुणान् श्रेयस्करान् दोषवतश्च परीक्षेत सम्यक्... ||18|| (Charaka Samhita, Vimana Sthana, Adhyaya 8)[6]

prāgēva ca jalpājjalpāntaraṁ parāvarāntaraṁ pariṣadviśēṣāṁśca samyak parīkṣēt |...parīkṣamāṇastu khalu parāvarāntaramimān jalpakaguṇān śrēyaskarān dōṣavataśca parīkṣēta samyak... ||18||

It is said that one should not participate in a debate with superior opponent nor immediately defeat the inferior with tricky procedures. The debaters are to be acquainted with certain logical terms known as the 44 Vada marga pada which decide the victory of a debater over the opponent. These mostly consist of[3]

- 5 Avayavas

- 6 Padarthas

- Vada

- Sthapana

- 6 Pramanas

- Pratisthapana

- Uttara

- Siddhanta

- Samshaya

- Paryojana

- Jijnasa

- Vyavasaya

- Sambhava

- Anujojya

- Anuyoga

- Pratyanuyoga

- Vakyadosha

- Vakyaparshamsa

- Chala

- Ahetu

- Atitakala

- Upalambha

- Parihara

- Pratijnahani

- Abhayanujna

- Hetvantara

- Arthantara

- Nigrahasthana

इमानि तु खलु पदानि भिषग्वादमार्गज्ञानार्थमधिगम्यानि भवन्ति; तद्यथा-वाद:, द्रव्यं, गुणाः, कर्म, सामान्यं, विशेषः, समवायः, प्रतिज्ञा, स्थापना, प्रतिष्ठापना, हेतुः, दृष्टान्तः, उपनयः, निगमनम्, उत्तरं, सिद्धान्तः, शब्दः, प्रत्यक्षम्, अनुमानम्, एतिह्यम्, औपम्यम्, संशयः, प्रयोजनं, सव्यभिचारं, जिज्ञासा, व्यवसायः,अर्थप्राप्तिः,संभवः, अनुयोज्यम्, अनुयोगः, प्रत्यनुयोगः, वाक्यदोषः, वाक्यप्रशंसा, छलम्, अहेतुः, अतीतकालम्, उपालम्भः, परिहारः, प्रतिज्ञाहानिः, अभ्यनुज्ञा, हेत्वन्तरम्, अर्थान्तरं, निग्रहस्थानमिति ||27|| (Charaka Samhita, Vimana Sthana, Adhyaya 8)[6]

imāni tu khalu padāni bhiṣagvādamārgajñānārthamadhigamyāni bhavanti; tadyathā-vāda:, dravyaṁ, guṇāḥ, karma, sāmānyaṁ, viśēṣaḥ, samavāyaḥ, pratijñā, sthāpanā, pratiṣṭhāpanā, hētuḥ, dr̥ṣṭāntaḥ, upanayaḥ, nigamanam, uttaraṁ, siddhāntaḥ, śabdaḥ, pratyakṣam, anumānam, ētihyam, aupamyam, saṁśayaḥ, prayōjanaṁ, savyabhicāraṁ, jijñāsā, vyavasāyaḥ, arthaprāptiḥ,s aṁbhavaḥ, anuyōjyam, anuyōgaḥ, pratyanuyōgaḥ, vākyadōṣaḥ, vākyapraśaṁsā, chalam, ahētuḥ, atītakālam, upālambhaḥ, parihāraḥ, pratijñāhāniḥ, abhyanujñā, hētvantaram, arthāntaraṁ, nigrahasthānamiti ||27||

न्यायसूत्राणि || Nyaya Sutras

Debates, according to Akshapada's Nyayasutras, can be of three types:

- An honest debate (called Vada) where both sides, proponent and opponent, are seeking the truth, that is, wanting to establish the right view.

- A tricky-debate (called Jalpa) where the goal is to win by fair means or foul.

- A destructive debate (called Vitanda) where the goal is to defeat or demolish the opponent, no matter how.

The first kind signals the employment of logical arguments, and use of rational means and proper evidence to establish a thesis. It is said that the participants in this kind of debate were the teacher and the student, or the students themselves, belonging to the same school.

The second was, in fact, a winner-takes-all situation. The name of the game was wit or intelligence. Tricks, false moves, and unfair means were allowed according to the rules of the game. But if both the debaters were equally clever and competent, this could be kept within the bounds of logic and reasoning. Usually, two teachers of different schools would be participants. This used to take place before a board or jury called the madhyastha (the mediators or adjudicators) and a chairman, usually a Raja or a man with power and money who would organize the debate. The winner would be declared at the end by the consensus of the adjudicators.

The notoriety of the third type was universal, although some philosophers (for example, Nagarjuna, Sri Harsha) maintained that if the refutations of the opponent were done on the basis of good reason and evidence (in other words, if it followed the model of the first type, rather than the second type) then lack of a counter-thesis, or non-establishment of a counter-thesis, would not be a great drawback. In fact, it could be made acceptable and even philosophically respectable. That is why Gauda Sanatani divided the debates into four types:

- the honest type (Vada)

- the tricky type (Jalpa)

- the type modeled after the tricky type (Jalpa) but for which only refutation is needed

- the type modeled after the honest one (Vada) where only the refutation of a thesis is needed

Even the mystics would prefer this last kind, which would end with a negative result.[1]

वादप्रकाराः ॥ Types of debates

In the Indian traditions, four formats of discussions, debates or arguments are described. Namely,

- Samvada (संवादः)

- Vada (वादः)

- Jalpa (जल्पः)

- Vitanda (वितण्डा)

The merit and esteem of each of these types of discussions is graded in terms of

- the honesty of their purpose

- the quality of debate

- the decorum

- the mutual regard of the participants

While Samvada is a discourse or imparting of teaching, the other three – Vada, Jalpa and Vitanda- are clever and structured (based on tantrayukti) debates or arguments between rivals.[2]

विषयविस्तारः ॥ Detailed Discussion

According to the commentaries on the Nyaya Sutras, the debates and arguments are grouped under a broad head titled ‘Katha’. In Sanskrit, the term ‘Katha’, in general, translates as ‘to inform’, ‘to narrate’, ‘to address or 'to refer to somebody’. In the context of the Nyaya Shastra, which provides the knowledge about the methods for presenting arguments (Vako-Vakya or Vada Vidya) as also the rules governing the debates, the term ‘Katha’ implies formal conversation (Sambhasha) as in a debate. The conversation here, is not in the casual manner as in day-to-day life. But, it is articulate, precise and well thought out utterances. Thus, Katha here, is described as ‘polemical conversation’, meaning that it is passionate and strongly worded, but a well balanced argument against or in favor of somebody or something. That is why, the discussions (Vada) are never simple. In essence, a Katha is a reasoned and well-structured philosophical discussion.[2]

Vatsyayana at the beginning of his commentary on the Nyaya Sutra (1.2.1) mentions that Katha is of three types:

- Vada (Discussion)

- Jalpa (Disputation)

- Vitanda (Wrangling)[7]

तिस्रः कथा भवन्ति वादो जल्पो वितण्डा चेति ।[8] tisraḥ kathā bhavanti vādo jalpo vitaṇḍā ceti ।

Udyotakara in his Nyaya Varttika further explains that this threefold classification is according to the nature of the debate and the status of the persons taking part in the debate.

- The first variety, Vada, is an honest, peaceful and congenial (sandhaya) debate that takes place between two persons of equal merit or standing, trying to explore the various dimensions of a subject with a view to ascertain and establish ‘what is true’. The Vada, at its best, is a candid friendly discussion (anuloma sambhasha or sandhaya sambhasha) or debate in the spirit of: ’let’s sit-down and talk’.

- The other two are hostile arguments (vigrhya sambhasha) between rivals who desperately want to win.

Thus, by implication, the goal of a Vada is establishment of truth or an accepted doctrine; while that of the other two hostile debates, Jalpa and Vitanda, is seeking victory on the opponent.[2] Thus, the three types of Katha in terms of the two kinds of Sambhasha mentioned earlier can be summarized as in Fig. 1.

संवादः ॥ Samvada

The commentary on the Nyaya sutras describes Samvada as समाय वाद: । samāya vāda: ।

Meaning: Discussion for the sake of coming to an agreement.[7]

Of the four forms of discussions, Samvada is regarded the noblest type. It is a dialogue that takes place between an ardent seeker of truth and an enlightened teacher.[2][9] Samvada is thus, a dialogue that teaches, imparts instructions or passes on knowledge.[2] In fact, most of the ancient Indian texts are in this format.[2][9] The bulk of the Upanishadic teachings also have come down to us in the form of Samvada, which took place in varieties of contexts. The one who approaches the teacher could be,

- A disciple or student.

- A friend as in Krishna-Arjuna Samvada or Krishna-Uddhava Samvada.

- A Son as in Uddalaka-Shvetaketu Samvada.

- A Spouse as in Shiva-Parvati Samvada or Yajnavalkya-Maitreyi Samvada where a wife is curious to learn from her husband the secrets of immortality.

- Or anyone else seeking knowledge as in Yama Nachiketa Samvada where a teenage boy approaches Yama to learn the truth of life and death or the six people who approach Sage Pippalada in Prashna Upanishad.

There are also instances when a Raja seeks instruction from a recluse sage who speaks from his experience, brahmanas advanced in age and wisdom sit at the feet of a Kshatriya prince seeking instructions as also inspiration, etc. In fact, in the Chandogya Upanishad, there are instances of dialogue where Rshi Jabala is taught by bulls and birds (4.4-9), Upakosala by the sacred fires (4.10-15) and Baka by a dog (1.12).[2]

It is said that, this type of discussion can occur only when the student surrenders himself completely at the feet of the teacher.[2][9] Thus, what characterizes Samvada in such cases is

- the sincerity and eagerness of the learner

- the humility in his/her approach

- the absolute trust in the teacher.

In fact, the Bhagavad Gita suggests that an ardent seeker of truth should approach a learned teacher in humility and seek instructions from him; and question him repeatedly.[2]

तद्विद्धि प्रणिपातेन परिप्रश्नेन सेवया । उपदेक्ष्यन्ति ते ज्ञानं ज्ञानिनस्तत्त्वदर्शिनः ॥४-३४॥[10]

tadviddhi praṇipātena paripraśnena sevayā । upadekṣyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninastattvadarśinaḥ ॥4-34॥

Even in the Upanishads, nothing is more vital than the relationship between a student and his guide. The teacher talks, out of his experience, about his ideas of the nature of the world, of truth etc. or about particular array of phenomena visualized through mental images that stay etched in memory. An Upanishad teacher ignites in the heart of the student a spark that sets ablaze his desire to learn and to know the central principles which make sense of the world we live in. The guide inflames the sense of challenge, the urge to reach beyond the student’s grasp and to know the unknown.[2]

The student also, questions the teacher not because he doubts the wisdom or the understanding of the teacher; nor because he doubts the authenticity of the teaching. In fact, the student here, does not question the teacher but questions his own understanding for clarification. The questions are asked with an open mind and guileless heart to clear doubts and to gain a flawless understanding of the teaching. And the wise teacher, in turn, gracefully imparts instructions out of enormous love for the ardent seeker of truth. The teacher is neither annoyed nor does he discourage the student from asking questions. Rather, he encourages the learner to examine, enquire and test the teaching handed down to him. A true teacher, in a Samvada, does not prescribe or proscribe. He lets the student have the freedom to think, to ponder over and to find out for himself the answers to his questions. All a student needs is humility, persistence and honesty of purpose to go further and to arrive at his own understanding.[2]

This topic of Samvada is handled towards the conclusion of the 4th Adhyaya of the Nyaya sutras. It says,

ज्ञानग्रहणाभ्यासस्तद्विद्यैश्च सह संवादः ॥ ४.२.४६ ॥। तं शिष्यगुरुसब्रह्मचारिविशिष्टश्रेयोऽर्थि-भिरनसूयुभिरभ्युपेयात् ॥ ४.२.४७ ॥ प्रतिपक्षहीनमपि वा प्रयोजनार्थमर्थित्वे ॥ ४.२.४८ ॥[11]

jñānagrahaṇābhyāsastadvidyaiśca saha saṁvādaḥ ॥ 4.2.46 ॥। taṁ śiṣyagurusabrahmacāriviśiṣṭaśreyo'rthi-bhiranasūyubhirabhyupeyāt ॥ 4.2.47 ॥ pratipakṣahīnamapi vā prayojanārthamarthitve ॥ 4.2.48 ॥

Meaning: (For the purpose of attaining apavarga) There should also be repetition of the study of the science, as also samvada (friendly discussion) with persons learned in the science. That samvada should be carried on with the pupil, the teacher, companions in study, and other well-known learned persons, who wish well (to the enquirer) and who are not jealous of him. In fact, being a seeker (of truth), one should carry it on even without putting forward any counter theories for the accomplishment of his purpose. For, putting forward of theories and counter theories would be unpleasant to the other person. More so if the other person in this case is a teacher.[7] The bhashya explains further that,

ज्ञायतेऽनेनेति ज्ञानमात्मविद्याशास्त्रम् । तस्य ग्रहणमध्ययनधारणे अभ्यासः सततक्रियाऽध्ययनश्रवणचिन्तनानि तद्विद्यैश्च । सह संवाद इति प्रज्ञापरिपाकार्थे परिपाकस्तु संशयच्छेदनमविज्ञातार्थबोधोऽध्यवसिताभ्यनुज्ञानमिति । समापवादः संवादः । वा.भा. ।[8]

jñāyate'neneti jñānamātmavidyāśāstram । tasya grahaṇamadhyayanadhāraṇe abhyāsaḥ satatakriyā'dhyayanaśravaṇacintanāni tadvidyaiśca । saha saṁvāda iti prajñāparipākārthe paripākastu saṁśayacchedanamavijñātārthabodho'dhyavasitābhyanujñānamiti । samāpavādaḥ saṁvādaḥ । vā.bhā. ।

Jnana here refers to 'that by which things are known' ie. the science of atmavidya. And Jnana grahana (acquisition of that knowledge) consists in reading it and retaining it in the mind. The repetition of such study means the carrying on of it continuously, in the shape of reading it, listening to it (being expounded) and pondering over it. And the purpose of Samvada with persons learned in the science is to bring about consolidation of the knowledge acquired. This consolidation consists in,

- the removing of doubts

- the knowing of things not already known

- the confirmation of the conclusions already arrived by oneself through the opinions of the learned[7]

वादः ॥ Vada

Vada, in general, is described as a debate between two people of equal standing to establish the truth/to resolve a conflict.[12][9] The term Vada by itself means a theory, doctrine or thesis.[2] Nyaya Sutra (1.2.1) states that

प्रमाणतर्कसाधनोपालम्भः सिद्धान्ताविरुद्धः पञ्चावयवोपपन्नः पक्षप्रतिपक्षपरिग्रहः वादः ।।१.२.१।।[13]

pramāṇatarkasādhanopālambhaḥ siddhāntāviruddhaḥ pañcāvayavopapannaḥ pakṣapratipakṣaparigrahaḥ vādaḥ ।।1.2.1।।

Meaning: Vada (Discussion) consists in the putting forward (by two people) of a conception and a counter-conception, in which there is supporting and condemning by means of proofs and reasonings - neither of which is quite opposed to the main doctrine (or thesis), and both of which are carried on in full accordance with the method of reasoning through the five factors.[7]

According to this definition, Vada necessarily takes place between 2 people or 2 groups. Out of the two, the proponent who puts forward arguments in support of his doctrine (Vada) is termed as Vadin. While the opponent who refutes that theory through his counter-arguments is termed as Prati-vadin. Thus, unlike in Samvada, there is no teacher-taught relationship here; nor is it a discourse.[12] However, Vatsayana in his commentary Nyaya Bhashya, explains further that Vada or Anuloma Sambhasha (congenial debate) can take place only when the opponent is

- Not wrathful or malicious

- Learned, wise, eloquent and patient

- Well versed in the art of persuasion

- Gifted with sweet speech.

Because the principal aim of a wholesome Vada is to resolve the conflict and to establish ‘what is true’.[2]

वादप्रयोजनम् || Purpose of Vada

Vada can take place between scholars of the same subject or those with contrary views.

- When a learned person debates with another scholar versed in the same subject, it increases the depth of their knowledge, clears misapprehensions, if any, and leads them to find certain minor details which hitherto might have escaped their attention. Besides, it also heightens their zeal to study further and bring happiness to both.

- When the scholars hold contrary views, both the Vadin and Prativadin each try very hard to establish the doctrine which he believes is true and try to convince the other to accept its veracity through fair and effective presentation and arguments. However, each is also willing to understand and appreciate the arguments of the other and accept any merit they might find in it. In fact, if one of them is in doubt or is unable to respond satisfactorily, he can take a break to re-group his position or to re-examine the issue to see whether he can refute the opponent’s argument more effectively or put up a sounder defense. And, if one is convinced that the doctrine and the argument presented by the opponent is valid, he adopts it with grace. At the end, one of the two is proven wrong or both could be right. In any case, they accept the outcome of the debate and part their ways without rancor.[2]

Therefore, Vada is called an honest debate and both parties are expected to

- Have mutual regard and respect for each other’s learning and status

- Participate with an open mind in order to explore various dimensions of the subject on hand

- Examine the subject thoroughly by applying the accepted norms of logic and reasoning (Tarka)

- Support the reasoning with passages from texts of undisputed authority (Shabda Pramana).[12]Like, in case of Vedantic discussions, the Pramanas are specifically the Prasthana Trayi - The Upanishads, Brahma Sutras and Bhagavad Gita. [9]

Thus, Vada is characterized by politeness, courtesy and fair means of presenting the arguments. In other words, it is a healthy discussion[2] that culminates in learning as, at the end, truth gets established to the satisfaction of both parties.[12]

Role of the Madhyastha

A Vada generally takes place in front of a board or jury called the Madhyastha (the mediators or adjudicators) to ensure that the discussion proceeds along the accepted pramanas.[1][9]At the commencement of the Vada, it is the Madhyastha (Judge or arbiter) who lays down rules of the Vada. And the disputants are required to honor these norms and regulations. They are also required to adhere to permissible devices and not breach certain agreed limits known as Vada maryada. For example: If both the Vadin and Prativadin belong to the Vedic tradition, they are not permitted to question the validity of the Vedas or the existence of Supreme being and the Atman. And any position taken during the course of the Vada cannot contradict the Vedic injunctions. Similarly, if one of the proponents belongs to the Vedic tradition and the other to a Non-Vedic tradition, both have to abide by the rules and discipline specifically laid down by the Madhyastha.[2]

As mentioned earlier, according to the Nyaya Sutra (1.2.1), Vada comprises defense and attack (Sadhana and Upalambha). That is, one’s own thesis is defended by means of genuine criteria of knowledge (Pramana) while, the antithesis (opponent’s theory) is refuted by negative dialectics of Tarka (logic). However, when defense or attack is employed excessively, merely for the sake of scoring a win, then there is the risk of the debate degenerating into Jalpa. It is at this stage in the Vada that the Madhyastha might intervene to ensure that the participants, especially the one who is on the verge of defeat (Nigrahasthana) does not resort to tricks such as quibbling (Chala), false rejoinder (Jati) etc. In such cases, the Madhyastha may even call off the Vada and declare the candidate who, in his view performed better, as the winner.[2]

वादपरिणामः || Result of the Vada

It is seen that, a Vada proceeds until one accepts the others' arguments.[9] And the winner is declared, at the end, by the consensus of the adjudicators.[1] However, this can take days as is understood from the famous episode of a Vada between Adi Shankaracharya and Mandana Mishra In fact, it was Bharati, Mandana Mishra's wife and a great scholar herself, who had served as a judge for this Vada.[9] Therefore, one of the two proponents has to be silenced in order to establish a thesis as proved.

A Vada can also be treated as concluded and one side declared as defeated when,

- A proponent misunderstands his own premises and their implications

- The opponent cannot understand the proponent’s argument

- Either party is confused and becomes helpless

- Either is guilty of faulty reasoning or pseudo-reasoning (hetvabhasa) because, no one should be allowed to win using a pseudo-reason.

- One cannot reply within a reasonable time.

The Madhyastha may also treat the Vada as inconclusive (savyabhichara) if

- there is no possibility of reaching a fair decision

- the very subject to be discussed is disputed (Viruddha)

- the arguments stray away from the subject that is slated for discussion (prakarana-atita)

- the debate prolongs beyond a reasonable time (Kalatita).

Hence, in Vada, there is no explicit ‘defeat’ as such. The sense of defeat (Nigrahasthana) becomes apparent only when there are contradictions in logical reasoning (hetvabhasa) and the debate falls silent. In any case, when the doctrine and the argument presented are valid, it is to be adopted with grace.[2]

वादप्रसङ्गः || An Incident of Vada

The most celebrated Vada is said to be the one that took place between young Sri Shankara and the distinguished Mimamsa scholar and householder, Sri Mandana Mishra. It is said that, considering the young age of the opponent, Mandana Mishra generously offered Sri Shankara the option to select the Madhyastha (Judge) for the ensuing debate. At the same time, Sri Shankara, who had great respect for Sri Mandana Mishra's righteousness, chose his wife Bharati Devi, a wise and learned person as the Madhyastha. It is noted that, during the course of the lengthy debate when Mandana Mishra seemed to be nearing Nigrahasthana (clincher), Bharati Devi raised questions about marital obligations. Sri Shankara being a sanyasi had, of course, no knowledge in such matters. Thus, he requested for and obtained a ‘break’ to study and understand the issue. He then returned after some time equipped with the newly acquired knowledge, renewed the Vada and won it. Thereafter, Mandana Mishra accepted Sri Shankara as his teacher, with grace and respect.[2]

जल्पः ॥ Jalpa

As mentioned before, Vada is classified as a ‘good’ debate known as Sandhaya Sambhasha or Anuloma Sambasha (a congenial debate) while, Jalpa along with Vitanda is treated as 'hostile' argument (Vigrhya Sambasha).[2] Of the two types of hostile debates, Jalpa (disputation) is described, in Nyaya Sutra 1.2.2, as that which is endowed with the said characteristics of Vada and in which there is supporting and condemning by means of Chala (casuistry/quibbling), Jati (futile/irrelevant rejoinders provoking the opponent to lose focus) and Nigrahasthana (Clinchers).[7]

यथोक्तोपपन्नः छलजातिनिग्रहस्थानसाधनोपालम्भः जल्पः | १.२.२ |[13] yathoktopapannaḥ chalajātinigrahasthānasādhanopālambhaḥ jalpaḥ | 1.2.2 |

Jalpa is essentially a ’tricky’ debate between two rivals, where each is thoroughly convinced that he is absolutely right and the other (termed as the opponent – Prativadin) is hopelessly wrong. The first party to the debate is dogmatically committed to his own thesis, while the other party takes a rigid contrary position (Pratipaksha) on a given subject and sometimes, even at the cost of truth.[2]Also, as each discussor comes to the table with a preconceived notion that he is right and the other is wrong, the purpose of the discussion is not to discover or establish the truth but to establish one’s own position or thesis, and to prove the opponent wrong and convert the other to one's own camp. Therefore, each tries to win the debate by fair or foul means. And each is prepared to employ various deceptive or sophistic devices for the same. Some such devices used to outwit the opponent are

- Quibbling (Chala)

- Unreasonable responses (Ahetu)

- Shifting of reason (Hetvantara) or Shifting of topics (Arthantara)

- Irrelevant rejoinders (Jati) provoking the opponent to lose focus, etc.

Thus, Jalpa could, predictably, be noisy and unpleasant. Because, when one edges towards losing the argument (nigrahasthana), every sort of face-saving device or ruse is invented to wriggle out of the bad situation that is quickly turning worse.[12][9][2] Even if the proponent takes a break, it is only to come back with more ammunition to defend himself.[12]Therefore, there is hardly any knowledge that gets established in these discussions. However, if the bystanders don't have any preconceived notions, they can learn from the defects in each of the proponent's arguments during the discussion.[9]

जल्पसाधनानि ॥ Means of disputation

The main thrust of the arguments in Jalpa is not so much as to establish the thesis directly, as to disprove or refute the rival’s thesis. Thus, both the Vadin and the Prativadin work hard to establish their thesis through direct and indirect proofs. However, Jalpa relies more on tactics like discrediting the rival argument, misleading the opponent or willfully misinterpreting rival’s explanations. This is the reason why Jalpa is labeled as tricky. For, in Jalpa, apart from traditional means for proving one’s thesis and refuting the opponent’s thesis, the debater can use elusive and distracting devices such as,

- Quibbling or hair-splitting (Chala)

- Inappropriate rejoinders (Jati)

- Any kind of ruse that tries to outwit and disqualify the opponent

- Circumvention

- False generalization

- Showing the unfitness of the opponent to argue (even without establishing his own thesis), etc.

Nyaya Sutra gives a fairly detailed treatment to the tactics employed during Jalpa.[2] According to the Nyaya Sutras, there are

- Three kinds of quibbling (Chala)

तत्त्रिविधं वाक्छलं सामान्यच्छलं उपचारच्छलं च इति ।।१.२.११।।[13] tattrividhaṁ vākchalaṁ sāmānyacchalaṁ upacāracchalaṁ ca iti ।।1.2.11।।

- Twenty-four kinds of inappropriate rejoinders (Jati)

साधर्म्यवैधर्म्योत्कर्षापकर्षवर्ण्यावर्ण्यविकल्पसाध्यप्राप्त्यप्राप्तिप्रसङ्गप्रतिदृष्टान्तानुत्पत्तिसंशयप्रकरणहेत्वर्थापत्त्यविशेषोपपत्त्युपलब्ध्यनुपलब्धिनित्यानित्यकार्यसमाः ॥ ५.१.१ ॥[14]

sādharmyavaidharmyotkarṣāpakarṣavarṇyāvarṇyavikalpasādhyaprāptyaprāptiprasaṅgapratidr̥ṣṭāntānutpattisaṁśayaprakaraṇahetvarthāpattyaviśeṣopapattyupalabdhyanupalabdhinityānityakāryasamāḥ ॥ 5.1.1 ॥

- Twenty-two kinds of clinchers or censure-situations (Nigrahasthana).

प्रतिज्ञाहानिः प्रतिज्ञान्तरं प्रतिज्ञाविरोधः प्रतिज्ञासंन्यासो हेत्वन्तरमर्थान्तरं निरर्थकमविज्ञातार्थमपार्थकमप्राप्तकालं न्यूनमधिकं पुनरुक्तमननुभाषणमज्ञानमप्रतिभा विक्षेपो मतानुज्ञा पर्यनुयोज्योपेक्षणं निरनुयोज्यानुयोगोऽपसिद्धान्तो हेत्वाभासाश्च निग्रहस्थानानि ॥५.२.१ ॥[14]

pratijñāhāniḥ pratijñāntaraṁ pratijñāvirodhaḥ pratijñāsaṁnyāso hetvantaramarthāntaraṁ nirarthakamavijñātārthamapārthakamaprāptakālaṁ nyūnamadhikaṁ punaruktamananubhāṣaṇamajñānamapratibhā vikṣepo matānujñā paryanuyojyopekṣaṇaṁ niranuyojyānuyogo'pasiddhānto hetvābhāsāśca nigrahasthānāni ॥5.2.1 ॥

It is said that such measures or tricks to outwit the opponent are allowed in Jalpa arguments, since the aim of the debate is to score a victory. However, those maneuvers are like double-edged swords; they cut both ways. Over-indulgence with such tactics is, therefore, rather dangerous as one runs the risk of being censured, descaled unfit and treated as defeated, if the opponent catches him at his own game.[2]

छलम् ॥ Chala

Chala (Quibbling), as mentioned above, is basically of three types.

- Vak Chala that is 'an attempt to misinterpret the meaning of an expression.'

अविशेषाभिहिते अर्थे वक्तुः अभिप्रायातर्थान्तरकल्पना वाक्छलम् ।।१.२.१२।।[13]

aviśeṣābhihite arthe vaktuḥ abhiprāyātarthāntarakalpanā vākchalam ।।1.2.12।।

For example: When one says, 'the boy has a nava kambala (new blanket)'; the opponent would look horrified and exclaim, 'why would a little boy need nava (nine) blankets !'

- Samanya Chala that refers to 'improperly generalizing the meaning of an argument.'

सम्भवतः अर्थस्य अतिसामान्ययोगातसम्भूतार्थकल्पना सामान्यच्छलम् ।।१.२.१३।।[13]

sambhavataḥ arthasya atisāmānyayogātasambhūtārthakalpanā sāmānyacchalam ।।1.2.13।।

For example: When one says, 'he is a hungry man (purusha)'; the opponent would generalize Man (Purusha) as ‘humans’ and ask, 'why are all the human beings hungry ?'

- Upachara Chala which is 'conflation of an ordinary use of a word with its metaphorical use with a view to derange the argument.'

धर्मविकल्पनिर्देशे अर्थसद्भावप्रतिषेधः उपचारच्छलम् ।।१.२.१४।।[13]

dharmavikalpanirdeśe arthasadbhāvapratiṣedhaḥ upacāracchalam ।।1.2.14।।

For example: Interpreting ordinary use of the term ‘mancha’ meaning a cot as it's metaphorical meaning like 'platform' or 'dais' or 'the people sitting on it'.[2]

जातिः ॥ Jati

Jati (Improper rejoinder or futile rejoinder) refers to 'falsifying the analogy given'; sometimes to the extent of ridiculing it.

For example: When one says, 'sound is impermanent because it is a product, such as a pot'; the opponent would ignore the ‘impermanent’ property of the analogy (pot) and rather pick up a totally unrelated property of the analogy like the hollow space or emptiness in the pot and say, 'a pot is filled with space (akasha) which is eternal, then how could you say that a pot is impermanent ? And, further pot is not audible either.'[2]

निग्रहस्थानम् ॥ Nigrahasthana

Nigrahasthana variegatedly referred to as Clinchers, Censures, the defeat situation, etc. is the point at which Jalpa could be force-closed. The Nyaya sutras enlist 22 such cases or situation-types where the debate will be concluded and one side will be declared as "defeated". Some cases where Nigrahasthana could be enforced is by pointing out that

- the opponent is arguing against his own thesis.

- the opponent is willfully abstracting the debate.

- the opponent is using inappropriate ways.

- the opponent cannot understand the proponent's argument.

- the opponent is confused.

- the opponent isn't able to reply within a reasonable time limit, etc.

All these above mentioned situations will be considered cases of defeat. Thus, if the opponent is using any type of Nigrahasthana in his discussion and loses his proposition without explaining the relevant reasoning and evidence in its favour, he will be considered as defeated in debate.[3][1]

जल्पसाधनप्रयोजनानि ॥ Need for means of disputation

Explaining the need for a debater to resort to tactics such as Chala and Jati, and the need to invest time and effort in learning these tactics, Bimal Krishna Matilal in his 'The Character of Logic in India' says,

"Udyotakara, in the beginning of his commentary on chapter five of the Nyaya Sutra explains that it is always useful to learn about these bad tricks, for at least one should try to avoid them in one’s own debate and identify them in the opponent’s presentation in order to defeat him. Besides, when faced with sure defeat, one may use a trick, and if the opponent by chance is confused by the trick, the debater will at least have the satisfaction of creating a doubt instead of courting sure defeat."[2]

यदा वादी परस्य साधनं साध्विति मन्यते लाभपूजाख्यातिकामश्च भवति तदा जातिं प्रयुङ्क्ते कदाचिदयं जात्युत्तरेणाकुलीकृतो नोत्तरं प्रतिपद्यते उत्तराप्रतिपत्त्या च निगृह्यते । अनभिधाने च जातिरेकान्तजयः परस्येत्यैकान्तिकात्पराजयाद्वरमस्तु संदेह इति युक्तो जातेः प्रयोगः ॥ न्या.वा. ॥[8]

yadā vādī parasya sādhanaṁ sādhviti manyate lābhapūjākhyātikāmaśca bhavati tadā jātiṁ prayuṅkte kadācidayaṁ jātyuttareṇākulīkr̥to nottaraṁ pratipadyate uttarāpratipattyā ca nigr̥hyate । anabhidhāne ca jātirekāntajayaḥ parasyetyaikāntikātparājayādvaramastu saṁdeha iti yukto jāteḥ prayogaḥ ॥ nyā.vā. ॥

It is said that Jalpa way of arguments is at times, useful as a defensive measure to safeguard the real debate (Vada). Just as, the thorns and branches are used for the protection of the (tender) sprout of the seed. If a person without adequate skills enters into a debate, he might not be able to come up with proper rejoinder at the right time to safeguard his thesis. In such a crisis, he may get away with such a tricky debate. In any case, if the opponent is not quick witted, the (novice) debater may gain some time to think of the proper reason. Thus, he may even win the debate and the sprout of his knowledge would be protected. In this way, Jalpa tactics may come in handy to a novice or an inexperienced debater. However, this justification was not altogether acceptable.

Some other reasons that defend the Jalpa way of arguments are as follows:

- The flexibility of the Sanskrit language is considered one of the reasons for the diverse interpretation of the terms in the debate. For, in Sanskrit language,

- Compound words can be split in ways to suit one’s argument

- Words carry multiple meanings

- Varieties of contextual meanings can be read into, with change in structure of phrases, sentences and context of topics.

- The Sutra format of the ancient texts that make them terse, rigid and ambiguous is another reason. For, they can not only be read and interpreted in any number of ways but each interpretation can also be supported by one or the other authoritative text. Therefore, there is plenty of scope for legitimate disputation.[2]

Besides, these manuals identify several standard "false" rejoinders or jati (24 of them are listed in the Nyayasutra), as well as some underhand tricks (chala) like equivocation and confusion of a metaphor for the literal.[1]

वितण्डा ॥ Vitanda

Vitanda is generally described as a destructive type of argument or squabbling that descends to the level of quarrel and trickery. Here, the sole aim of each participant is not only to inflict defeat on the opponent but also to demolish and humiliate him. Therefore, the debater who employs Vitanda, known as a Vaitandika, is basically a refuter.

- He relentlessly goes on refuting whatever the proponent says.

- He is aggressive and goes on picking holes in the rival’s arguments and destabilizes his position, without any attempt to offer an alternate thesis. In fact, it is said that, he has no thesis of his own – either to put forward or to defend.

- He might sometimes, pick up a thesis just for argument’s sake, even though he may have no faith in the truth of his own argument.

- He may also, pick up the opponent’s thesis (though he himself might not believe in it) and argue in its favor just to demonstrate that the opponent is not doing a ‘good job’. And rebuke him saying that the thesis itself might not be as bad as the opponent is making it out to be due to his arguments. By that, he tries to effectively undermine the credibility of the opponent and demonstrate to him that he is neither competent nor qualified to discuss the subtleties of logic.

- He makes it a point to disagree with the other, no matter what the other says. It is a way of saying, 'You are wrong, not because your statement by itself is wrong. It is wrong because you said it.'

In other words, the debater here, tries to ensure his victory simply by refuting or demolishing the thesis put forward by the other side; by browbeating, misleading or ridiculing the opponent. The whole purpose of the exercise seems to be to prove the opponent wrong and incompetent, and to humiliate him. Therefore, the major part of Vitanda is spent in denying the opponent’s views, in discrediting him or in quarreling. Thus, there is no place for either ‘valid knowledge’ or ‘truth’ in such type of debate.[2] In that sense, Vitanda is some what peculiar.[9] Hence, Nyaya-Sutra describes Vitanda as,

सः प्रतिपक्षस्थापनाहीनः वितण्डा ।।१.२.३।।[13] saḥ pratipakṣasthāpanāhīnaḥ vitaṇḍā ।।1.2.3।।

This definition of Vitanda becomes clearer as the difference between Jalpa and Vitanda are enumerated.

जल्पवितण्डयोः भेदः || Difference between Jalpa and Vitanda

| जल्पः || Jalpa[2] | वितण्डा || Vitanda |

|---|---|

| 1. The contending parties in a Jalpa have a position of their own that they fight hard to defend. | In Vitanda, the disputant has neither a position of his own nor is he trying to defend any specific thesis. He merely tries to derange and humiliate the other party to the debate.[2] |

| 2. In Jalpa, the aim of the contenders is to make the rival accept their thesis, by whatever means. | In Vitanda, the focus is to prove that the opponent is not qualified to discuss and that there is no credibility for the opponent.[9][12] |

| 3. Jalpa employs trickery such as quibbling and illegitimate rejoinder. But, it tries to argue for the success of its thesis by whatever means. | Vitanda also employs various tactics. But, does not seriously attempt to put up any counter-thesis.[2] |

Therefore, it is said that,

स जल्पो वितण्डा भवति किं विशेषणः प्रतिपक्षस्थापनया हीनः ।[8]

a jalpo vitaṇḍā bhavati kiṁ viśeṣaṇaḥ pratipakṣasthāpanayā hīnaḥ ।

Meaning: That Jalpa (disputation) becomes Vitanda (wrangling) which is devoid of counter conception.

It is mentioned here that the Wrangler does not establish the view (that which he himself holds), but only goes on to criticize the other person. Hence, it seems as though a disputation without a counter conception is Vitanda. However, according to Tatparya Tika, when the wrangler confines himself to merely criticizing the opponent's view, he does so with the idea that when the opponent's view has been rejected as wrong, it would follow as a necessary consequence that his own view is right, so he does have a view of this own; but it is stated in wrangling, only in the form of the attack on the other view, this criticism, being figuratively spoken of as his 'view'. So, the meaning is that though the wrangler has a view of his own, yet he does not make any attempt at establishing it, apart from the attack that he directs against the other view. Hence, it is only right to speak of there being no establishing of his own view but it would be wrong to say that there is no other view.[7]

Also, both the participants in a Vitanda are prepared to resort to mean tactics in order to mislead the opponent by fallacies (hetvabhasa), attack the opponents statement by willful misrepresentation (Chala) and ill-timed rejoinders (Atita-kala), etc. The participants try to effectively silence the opponent, though what they themselves say might be irrational or illogical. In fact, it is virtually akin to a ‘no-holds-barred’ sort of street fight. Thus, ethereal values such as truth, honesty, mutual respect and such others are conspicuously absent here. Therefore, in terms of merit, Vitanda is rated inferior to Jalpa.[2]

Role of a Madhyastha

In a Vitanda, where both the parties employ similar tactics, the debate would invariably get noisy and ugly. The Madhyastha or the Judge plays a crucial role in regulating a Vitanda. He has the hard and unenviable task of not merely controlling the two warring debaters and their noisy supporters, but also to rule on

- what is ‘Sadhu’ (permissible) or ‘A-sadhu’ (not permissible).

- what is true (Sat) what is just a bluff (A-sat).

And, when one debater repeatedly oversteps and breaches the accepted code of conduct, the Madhyastha might have to disqualify him and award the debate to the other. At times, he may even disqualify both the parties and scrap the event declaring it null and void.[2]

जल्पवितण्डयोः प्रयोजनम् अधिकारी च ॥ Prayojana and Adhikari of Jalpa and Vitanda

Explaining the need for Jalpa and Vitanda, it is said in the Nyaya Sutras and the corresponding bhashya that,

स्वपक्षरागेण चैके न्यायमतिवर्तन्ते तच ।[8] तत्त्वाध्यवसायसंरक्षणार्थं जल्पवितण्डे बीजप्ररोहसंरक्षणार्थं कण्टकशाखावरणवत् ॥ ४.२.४९ ॥[11]

svapakṣarāgeṇa caike nyāyamativartante taca । tattvādhyavasāyasaṁrakṣaṇārthaṁ jalpavitaṇḍe bījaprarohasaṁrakṣaṇārthaṁ kaṇṭakaśākhāvaraṇavat ॥ 50 ॥

Meaning: Through excessive partiality to their own theories, some people transgress all bounds of reasoning; in that case, Jalpa (disputation) and Vitanda (Wrangling) should be carried on for the purpose of defending one's own determination to get at the truth; just as the hedge of thorny branches is put up for the protection of sprouting seeds. The bhashya also clarifies further that,

अनुत्पन्नतत्त्वज्ञानानामग्रहीणदोषाणां तदर्थे घटमानानामेतदिति ।[8] anutpannatattvajñānānāmagrahīṇadoṣāṇāṁ tadarthe ghaṭamānānāmetaditi ।

Meaning: This method (of Jalpa and Vitanda) however, is meant only for those persons who have not acquired True knowledge, whose defects have not been entirely removed, and who are still making an attempt for those purposes.

It further says that,

When one has been rudely addressed by an opponent; either through arrogance (of superior knowledge), or through sheer prejudice (against truth), or through some other similar reasons (i.e.desire for wealth, fame, etc.) then one (failing to perceive the right answer to the ill-mannered allegations of the opponent) should pick up a quarrel with him and proceed to deal with him by Jalpa (disputation) and by Vitanda (wrangling). This quarrel is with a view to defeating the opponent and not with a view to getting at the truth. But this should be done only for the purpose of defending true Science, and not for the purpose of obtaining wealth, honour or fame.

According to the Tatparya Tika, the motive prompting the man should be - if this ill mannered person is allowed to go undefeated, then ordinary men will accept his conclusions as the right ones, and this would bring about a total confusion relating to dharma and true philosophy.[7]

विद्यानिर्वेदादिभिश्च परेणावज्ञायमानस्य ।[8] ताभ्यां विगृह्य कथनम् ॥ ४.२.५० ॥[11] विगृह्येति विजिगीषया न तत्त्वबुभुत्सयेति । तदेतद्विद्यापालनार्थं न लाभपूजाख्यात्यर्थमिति ।[8]

vidyānirvedādibhiśca pareṇāvajñāyamānasya । tābhyāṁ vigr̥hya kathanam ॥ 4.2.50 ॥ vigr̥hyeti vijigīṣayā na tattvabubhutsayeti । tadetadvidyāpālanārthaṁ na

वादजल्पयोः भेदः ॥ Difference between Vada and Jalpa

| वादः ॥ Vada[2] | जल्पः ॥ Jalpa[2] |

|---|---|

| 1. Vada is an honest debate aiming to ascertain ‘what is true’ | 1. Jalpa is an argument where each strives to impose his thesis on the other. The question of ascertaining the ‘truth’ does not arise here. |

| 2. In Vada, the thesis is established by Pramanas and the anti-thesis is disproved by Tarka or different set of Pramanas. | 2. In Jalpa, the main function is negation; the Pramanas do not have much use here. |

| 3. Jalpa in general could be the dialectical aid for Vada | 3. Jalpa tries to win the argument by resorting to quibbling, such as Chala, Jati and Nigrahasthana. None of these can establish the thesis directly, because their function is negation. But, indirectly, they help to disprove anti-thesis. |

| 4. In the case of Vada, the ‘truth’ is established by positive evidence and the invalid knowledge (A-pramana), masquerading as a good reason (that is, a hetvabhasa) is detected and eliminated. No one is really defeated and the truth is established. | 4. In the case of Jalpa, it mainly depends on negation (which is non-committal) and on effective refutation of the proponent’s argument. There is no earnest effort to build positive irrefutable proof. And, the fear of defeat overhangs the whole proceedings. |

Differences between Samvada, Vada and Vivada

Samvada is generally understood as a dialogue between those like the teacher and the taught. Whereas, Vada refers to systematic establishment of a theory through logical reasoning in a cordial manner. While, the use of negation techniques as in Jalpa and Vitanda, transform a discourse into Vivada. In the 3rd verse of the Upadesha Panchaka, Adi Shankaracharya says,

बुधजनैर्वादः परित्यज्यताम् ॥ ३ ॥ budhajanairvādaḥ parityajyatām ॥ 3 ॥

Meaning: May you never argue with wise people.

In this context, Shri.Yegnasubramanian explains subtle distinctions between Vada and Samvada which may be extended to Vivada as well. He says,

- In Vada and Vivada, one looks upon the opponent as equal or inferior respectively, where as, in samvada, one looks upon the other person as equal or superior (as in case of a teacher). Thus, there is a basic difference in the attitude itself which reflects in one’s addressing the other, the language, tone etc.

- When one enters into Vada or Vivada, one has often made one’s conclusion on a topic, and through the debate, one tries to establish one’s conclusion or refute the other. Whereas in Samvada, one has his/her conviction, but does not force it upon another as his/her conclusion. Like a student’s approach, where the student may have some opinions, or notions, but doesn't make a conclusion nor wants to refute the teacher’s conclusion or teaching. The person is open-minded, and willing to refine or improve his/her understanding.

- In the course of debates, one tries to talk more and focuses on restricting the other person from talking. The inclination to listen is lacking and one always interferes before the other has concluded. Whereas in Samvada, the propensity to talk is balanced with the propensity to hear/listen. In Samvada, one talks only as much as is required to present his/her idea briefly and, allows the other person also to talk and listens with 200% attention without interference. Just like a student who waits to see whether the teacher has anything more to say even after the teacher has stopped.

- In the course of debates, especially in Vivada, there is less scope to reflect upon later since one does not listen to the other. Whereas, in a samvada, one is constantly reflecting upon what he/she is speaking as well as reflecting upon what the other is speaking. This is another aspect of giving respect. Just as with the teacher, not only does one listen, but also reflects upon the thought giving maximum respect to the teacher.

- An aspect of Samvada is that a person inquires when any point spoken by the other person is unclear. Even after elaborate answering, if one is not convinced; there is scope to ask again. Just like Arjuna inquired from Krishna when he was unclear about anything Krishna spoke. However, in Vivada, there is almost no room for this.

- A Samvada or Vada never leaves disturbance or bitterness in the mind. But in Vivada, there is always disturbance or bitterness in the mind.

Thus, there is lot of difference between Samvada, Vada and Vivada. A student asking a question to the teacher is welcome and is a part of learning. While, one trying to argue with a mahatma is not. Therefore, Vivada is positively condemned and asking questions for clarification is encouraged.[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Bimal Krishna Matilal, Jonardon Ganeri & Heeraman Tiwari (1998), The Character of Logic in India, SUNY Press, p. 31.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 Sreenivasa Rao, Discussions, Debates and Arguments: Ancient India.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Rajpreet Singh, Veenu Malhotra, Rimpaljeet Kaur and Shashikant Bharadwaj (2016) , Comparative study of Sambhasha in Charaka Samhita with Sympoisums held in Modern Era, International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Edited by Debendra Nath Sen and Upendra Nath Sen, Charaka Samhita, Vimana Sthana, Chapter 8, Pg.no.329-30

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Edited and Published by Ayurvedic Society (Jamnagar, 1949), Charaka Samhita (Volume 5), Pg.no.328

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Acharya Priyavrata Sharma, Charaka Samhita, Varanasi: Chaukhambha.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Ganganatha Jha (1939), Gautama's Nyayasutras with Vatsyayana Bhasya, Poona: Oriental Book Agency.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Gangadhara Sastri Tailanga (1896), The Nyayasutras with Vatsyayana's Bhashya, The Viziangram Sanskrit Series (Volume IX), Benaras: E.J.Lazarus & Co.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Kuntimaddi Sadananda (2002), Types of arguments, Bhakti List Archives.

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 4.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Maharshi Gautama, Nyayasutras, Adhyaya 4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Dr T P Sasikumar, http://trueindia.blogspot.in/2005/03/samvaada-vaada-jalpa-vitanda.html

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Maharshi Gautama, Nyayasutras, Adhyaya 1, Ahnika 2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Maharshi Gautama, Nyayasutras, Adhyaya 5.

- ↑ S.Yegnasubramanian (2012), Upadesa Pancakam of Adi Sankaracarya - Part II, Paramartha Tattvam.