Samkhya Darshana (साङ्ख्यदर्शनम्)

There are the six systems of Hindu philosophy which are known as Shad Darsanas. They are:

- न्यायः Nyaya (Rishi Gautama)

- वैशेषिकः Vaiseshika (Rishi Kanada)

- साङ्ख्यः Samkhya (Kapila Muni)

- योगः Yoga (Maharishi Patanjali)

- पूर्वमीमांसा Poorva Mimamsa (Jaimini)

- उत्तरमीमांसा Uttara Mimamsa or वेदान्त Vedanta (Badrayana or Vyasa)

Samkhya sashtra or Sankhya (Sanskrit: साङ्ख्य शास्त्रम्) is one of the Shad Darshanas. Kapila Muni is the founder of Samkhya Darsana. The word Sankhya means number. The Samkhya system gives an enumeration of the twenty five principles of universe[1].

Detailed Discussion

The Samkhya system discusses an original primordial Tattva or principle called Prakriti, that which evolves or produces or brings forth (Prakaroti) everything else.

Core Concepts[1]

प्रत्यक्ष (Pratyaksha, Perception), अनुमान (Anumana, inference) and आप्त वाक्य (Apta Vakya, right affirmation or trustworthy testimony) are the three Pramanas or proofs in Samkhya system. The Word Apta means fit or right. It is applied to the Vedas or inspired teachers. Nyaya Darsana has four kinds of proofs: प्रत्यक्ष, अनुमान , उपमान, शब्द. The Mimamsakas recognise six kinds of proofs.

Dual Concept of Purusha and Prakriti[1]

Samkhya denies that anything can be produced out of nothing. It assumes the reality of Purusha and Prakriti, the knowing Self and the objects known. Prakriti and Purusha are Anadi (beginningless) and Ananta (infinite). Non-discrimination between the two is the cause for birth and death. Discrimination between Prakriti and Purusha gives Mukti (salvation). Both Purusha and Prakriti are Sat (real). Purusha is Asanga (unattached). He is consciousness, all-pervading and eternal. Prakriti is doer and enjoyer. Souls are countless.

Non-acceptance of Isvara or God[1]

The Samkhya system is called Nir-Isvara (Godless). It is atheistical. The Samkhyas do not believe in Isvara. They do not accept Isvara (God). The creation produced by Prakriti has an existence of its own, independent of all connection with the particular Purusha to which it is united. So the Sankhyas say that there is no need for an intelligent Creator of the world, or even of any superintending power.

Vedanta's perspective on this thought[1]

According to the Vedanta, Prakriti is non-intelligent. An intelligent Creator alone can have a thought-out plan for the universe. Prakriti is only a Sahkari (helper).

Theory of Evolution and Involution[1]

The Samkhya adopts the theory of evolution and involution. The cause and effect are the undeveloped and developed states of one and the same substance. There is no such thing as total destruction. In destruction the effect is involved into its cause. That is all.

There cannot be any production of something out of nothing. That which is not cannot be developed into that which is. There must be a material out of which a product is developed. Everything cannot occur everywhere at all times, and anything possible must be produced from something competent to produce it. That which does not exist cannot be brought into existence by an agent. It would be useless to grind ground-nut, unless the oil existed in it. The manifestation of the oil is a proof that it was contained in the groundnut and consequently, a proof of the existence of the source from which it is derived. The effect truly exists beforehand in its cause. This is one of the central features of the Samkhya system of philosophy. Cause is a substance in which the effect subsists in a latent form. Just as the whole tree world exists in a latent or dormant state in the seed, so also the whole world exists in a latent state in Prakriti, the Avyakta (unevolved), or Avyakrita (undifferentiated). The effect is of the same nature as the cause.

Fourfold Classification of the Twenty Five Tattvas (तत्व)[1]

The Samkhya gives a description of categories based on their respective productive efficiency viz:

- प्रकृति Prakriti, Productive

- प्रकृति-विकृति (Prakriti- Vikriti) Productive and Produced. These are seven in number.

- विकृति(Vikriti) Produced. These are sixteen in number.

- अनुभव रूप (Anubhavarupa) Neither Productive nor Produced. This is Purusha.

This fourfold classification includes all the twenty-five principles or Tatvas. Prakriti or Nature or Pradhana (chief) is purely productive. It is the root of all. It is not a product. It is a creative force, evolver, producer. Seven principles— बुद्धि (Buddhi, intellect), अहंकार (Ahankara, egoism) and the five तन्मात्र Tanmatras (subtle essences - the essence of sight, smell, taste, touch and sound)—are productions and Productive. Buddhi is productive, as Ahankara is evolved out of it. it is produced also, as it itself is evolved out of prakriti. Egoism is a production, as it is derived from intellect. It is productive, as it gives origin to the five Tanmatras. The subtle essences (Tanmatras) are derived from egoism. Hence they are productions. They give origin to the five elements. Hence they are productive.

The sixteen principles, the ten organs, the mind and the five elements, are productions only. They are unproductive, because none of them can give birth to a substance essentially different from itself. The Purusha or Spirit is neither a production, nor is it productive. It is without attributes.

The Object of the Samkhya Philosophy[1]

The enquiry into this system of philosophy is to find out the means for eradicating the three sorts of pain, viz•, Internal or Adhyatmika (e.g., fever and other diseases), Celestial or Adhidaivika (thunder, cold, heat, rain, etc.), and external or Adhibhautika (pain from animals, scorpion etc.), and the disease of rebirths. Pain is an embarrassment. It stands in the way of doing Yoga Sadhna and attaining Moksha or release.

According to Samkhya one who has the knowledge of the twenty five principles, annihilates this pain. The ultimate cessation of the three kinds of pain is the final goal of life.

Prakriti[1]

Prakriti means that which is primary, that which precedes what is made. It comes from 'Pra' (before) and `Kri' (to make). It resembles Vedantic concept of Maya. It is the one root of the universe. It is called Pradhana or the chief, because all effects are founded on it and lt is the root of the universe and of all objects. Prakriti is eternal, all pervading, immovable. It is one. It has no cause, but is the cause of all effects. Prakriti is independent and uncaused, while the products are caused and dependent. Prakriti depends only on the activity of its own constituent Gunas (metaphysical properties).

The Modifications of Prakriti[1]

Egoism is a form of intellect. it is the matter from which the senses and the rudimental elements are formed. The gross elements are forms of the rudimental elements. Intellect, egoism and the five subtle rudiments or Tanmatras are the effects of Prakriti. This creation, from the intellect down to the elements is brought about by the modifications of Prakriti. Having observed the effects, the cause (Prakriti) is inferred. Prakriti is imperceptible from its subtlety. It must therefore be inferred from its effects.

The Function of Prakriti[1]

Prakriti is the basis of all objective existence. Prakriti creates only when it comes into union with Purusha.

Gunas

Prakriti is composed of three Gunas of forces, called Sattva (purity, light, harmony), Rajas (passion, activity, motion) and Tamas (inertia, darkness, inertness, inactivity). Note that these Gunas are not the Nyaya-Vaiseshika Gunas. They are the actual substances or ingredients, of which Prakriti is constituted. They make up the whole world evolved out of Prakriti. They are not conjoined in equal quantities, but in varying proportions, one or the other being in excess. Just as Sat-Chit-Ananda is the Vedantic trinity, so also the Gunas are the Sankhyan trinity.

Interaction Between the Gunas[1]

Interaction between the three Gunas, Sattva, Rajas and Tamas leads to Evolution. The three Gunas are never separate. They support one another. They intermingle with one another. They form the very substance of Prakriti. All objects are composed of the three Gunas. The Gunas act on one another. Then there is evolution or manifestation. The Gunas are the objects. Purusha is the witness-subject. Prakriti evolves under the influence of Purusha. Mahat or Intellect, is the first product of the evolution of Prakriti. Ahankara arises after Buddhi. Mind is born of Ahankara. It carries out the orders of the will through the organs of action (Karmendriyas). It reflects and doubts (Sankalpa-Vikalpa). It synthesises the sense data into percepts. The mind takes part in both perception and action. There is no separate Prana Tattva in the Samkhya system. The Vedanta has a separate Prana Tattva. In the Samkhya system, mind, with the organs, produces the five vital airs. Prana is a modification of the senses. It does not subsist in their absence.

Characteristics of the Three Gunas[1]

Sattva always remains in equilibrium. When Sattva prevails, there is peace or tranquillity. Rajas is activity which is expressed as Raga-Dvesha, likes or dislikes, love or hatred attraction or repulsion. Tamas is that binding force with a tendency to lethargy, sloth and foolish actions. It causes delusion or non-discrimination. When Sattva is predominant, it overpowers Rajas and Tamas. When Rajas is dominant, it overpowers Sattva and Tamas. When Tamas is predominant, it overpowers Rajas and Sattva.

How Man is Affected by the Three Gunas[1]

There are three Gunas in every man. When Sattva prevails, he is calm and tranquil. He reflects and meditates. At other times, Rajas prevails in him and he does various sorts of worldly activities. He is passionate and active. Sometimes, Tamas prevails. He becomes lazy, dull, inactive and careless.

A Sattvic man is virtuous. Sattva makes a man divine and noble, Rajas makes him thoroughly human and selfish, and Tamas makes him bestial and ignorant.

The Purusha[1]

The Purusha or the Self is beyond Prakriti. It is eternally separate from the latter. Purusha is without beginning or end. It is without attributes and without qualities. It is subtle and omnipresent. It is beyond mind, intellect and the senses. It is beyond time, space and causality. It is the eternal seer. It is perfect and immutable. It is pure consciousness (Chidrupa).

The purusha is not the doer. It is the witness. The Purusha is like a crystal without any colour. It appears to be coloured by the different colours which are placed before it. It is not material. It is not a result of combination. Hence it is immortal. The Purushas or souls are infinite in number, according to the Samkhya. There are many Purushas. If the Purushas were one, all would become free if anyone attained Moksha.

The different souls are fundamentally identical in nature. There is no movement for the Purusha. It does not go anywhere when it attains freedom or release. Souls exist eternally separate from each other and from Prakriti. Each soul retains its individuality. It remains unchanged through all transmigrations. Each soul is a witness of the act of a separate creation, without taking part in the act.

So the Purusha is witness (Sakshi, साक्षी), a spectator (Drashta, दृष्टा), a by-stander (Madhyastha, मध्यस्थ), solitary (kaivalya, कैवल्य ) passive and indifferent (Udasina, उदासीन).

Inference of the Existence of the Purusha[1]

Intelligence cannot belong to the intellect, because the intellect is material and is the effect of Prakriti which is non-intelligent. If intelligence is absent in a cause, it cannot manifest itself in the effect. Therefore, there must be a distinct principle of intelligence and this distinct principle is Purusha or the Self.

There must be a Supervisor over and above Pradhana or Prakriti. The Supervisor is Purushs or the Self. Prakriti and its products are objects of enjoyment. There must exist an enjoyer who must be an intelligent principle. This intelligent enjoyer is Purusha or the Self. Just as chair and bench are for the use of another so also this body, senses and mind are for the use of the Self which is immaterial, as it is destitute of attributes and as it is beyond the Gunas. The Purusha is the witness of the Gunas. The Gunas are the objects. Purusha is the witness-subject. Hence, it is not affected by pleasure, pain and delusion which are attributes of the three Gunas, Sattva, Rajas and Tamas, respectively. If pain is natural to the Purusha and if the Purusha is not naturally free from the action of the Gunas, no salvation from rebirth is possible.

Purusha and Prakriti—A Contrast[1]

The characteristics of Prakriti and Purusha are contrary in nature. Purusha is consciousness, while Prakriti is non-consciousness. Purusha is inactive, while Prakriti is active. Purusha is destitute of Guna, while Prakriti is characterised by the three Gunas. Purusha is unchanging, while Prakriti is changing. The knower is Purusha. The known is Prakriti. The knower is the subject or the silent witness. The known is the visible object.

The Universe[1]

The world is evolved with its different elements when the equilibrium in Prakriti is disturbed. The countless Purushas exert a mechanical force on Prakriti which distracts the equipoise of Prakriti and produces a movement. Then the evolution of the universe starts.

The process of Evolution and Involution[1]

Prakriti is the root of the universe. Prakriti is both the material and the efficient cause of the universe. From this the prakriti emanates the cosmic Buddhi or Mahat. From Mahat proceeds the cosmic Ahankara or the principle of egoism. From this egoism emanate the ten senses and the mind on the subjective side, and the five subtle Tanmatras of sound, smell, taste, colour and touch on the objective side. From these Tanmatras proceed the five gross elements — earth, water, fire, air and ether.

Akasa (ether) has the property of sound which is the Vishaya or object for the ear. Vayu (air) has the property of touch which is the Vishaya for the skin. Tejas (fire) has the property of form or colour which is the Vishaya for the eye. Apas (water) has the property of taste which is the Vishaya for the tongue. Prithvi (earth) has the property of odour which is the Vishaya for the nose. Each of these elements, after the first, has also the property of the preceding besides its own.

During dissolution of the world, the products return by a reverse movement into the preceding stages of development , and ultimately into Prakriti. Earth merges in its cause, water. Water merges in fire, fire merges in air, air in Akasa and Akasa in Ahankara, Ahankara in Mahat, and Mahat in Prakriti. This is the process of involution. There is no end to Samsara or the play of Prakriti. This cycle of evolution and involution has neither a beginning nor an end.

The Process of Knowledge[1]

Before one engages in any matter, one first observes and considers, then one reflects and then determines. Then one proceeds to act. This ascertainment: "Such act is to be done by me" is the determination of the intellect (Adhyavasaya).

The intellect is an instrument Which receives the ideas and images conveyed through the organs of sense, and the mind, constructs them into a conclusive idea, and presents this idea to the Self. The function of the intellect is determination (Nischaya).

The mind is both an organ of sensation and action. The senses receive simple impressions from without. The mind cooperates with the senses, and the impressions are perceived. The mind ponders, the intellect determines, and egoism becomes conscious.

Agency belongs to egoism—the Ahankara or the I-maker—which is itself a product of Prakriti, but not to the Purusha or Self who is always a silent witness.

The functions of mind, intellect and egoism can be instantaneous as well as gradual.

Swami Sivananda says: " Intellect, egoism, mind and the eye see a form at once, in one instant, and come immediately to a conclusion. ("This is a jar."). The same three, with tongue, at once relish taste; with the nose smell; and so on with the ear and the skin. The function is also occasionally gradual. A man going along a road sees an object at a distance. A doubt arises in his mind whether it is a post or a man. He then sees a bird sitting on it. Then the doubt is removed. In above example the intellect makes a determination that it is a post only. Then the ego says - I am certain that it is a post only."

The intellect, the mind and egoism are the door-keepers. The five senses of perception or Jnana-Indriyas are the gates. The intellect is the instrument or organ which is the medium between the senses and the Self.

The Intellect and its Functions[1]

Tile intellect or the Buddhi is the most important of all the products of Prakriti. The senses present their objects to the intellect. The intellect exhibits them to the purusha. The intellect discriminates the difference between purusha and Prakriti.

The intellect is the instrument or organ which is the medium between the other organs and the Self. All ideas derived from sensation, reflection, or consciousness are deposited in the chief or great instrument, intellect, before they can be made known to the Self. They convey impressions or ideas with the properties or effects of pleasure, pain and indifference, accordingly as they are influenced by the qualities of Sattva (purity), Rajas (passion) or Tamas (darkness).

The intellect appears to be intelligent on account of the reflection of Purusha which is very near to it, though by itself, it is really non-intelligent.

The Jiva[1]

The Jiva is the soul in union with the senses. It is limited by the body. It is endowed with egoism. The reflection of Purusha in the Buddhi or intellect appears as the ego or the empirical soul. It is associated with ignorance and Karma. It is subject to pleasure and pain action and its fruits, and rotates in the cycle of births and deaths.

The Jiva is different from the Purusha, who is perfect. The Jiva must strive to attain the status of the Purusha. Every Jiva has in it the higher Purusha hidden within. It must become conscious of the real nature of the higher Purusha. Freedom or perfection is a return into one's true Self. It is the removal of an illusion which conceals one's true nature.

Liberation[1]

Purusha is eternally free. Union of Purusha with Prakriti due to non-discrimination is bondage; the failure to discriminate between Purusha and Prakriti is the cause of Samsara or bondage; and disunion of Purusha and Prakriti due to discrimination is emancipation. Release is not merging in the Absolute but isolation from Prakriti.

The objective of the Samkhya System is to effect the liberation of the Purusha or Self. This is done by conveying the correct knowledge of the twenty-four constituent principles of creation and rightly discriminating the Self from them.

How Release Is Effected When the separation of the soul from th by destruction of the effects of virtue ev)ody takes , ice and the ',11;c1 Prakriti ceases to act in respect to it, then theis If, the final and absolute emancipation or the final el beatitude. When the fruits of acts cease, and body bath gross ro and subtle—dissolves, Nature does not exist with respect to the individual soul. The soul attains the state called Kaivalya. It is freed from the three kinds of pain. The Linga-Deha or subtle body which migrates from one gross bpdy to another in successive births, is composed of intellect, egoism, mind, the five organs of knowledge, the five organs of action and thefive Tanmatras. The impressions of actions done in various births are imbedded in the subtle body. The conjunction of the Linga-Deha with the gross physical body Constitutes birth and separation of the Linga-Deha from the gross physical body is death. This Linga-Deha • destroyed by the knowledge of the Purusha. When oneattains perfect Knowledge, virtue and vice

hee°r1le destitute of causal energy, but the body contin ues for some time on account of the previous s"'toPpuplesde: ,jiust as after the action of the potter has rto the wheel continues to revolve owing to the entun,ll given to it.

is Nothing but Termination. of tot Relea— se- Play of Prakriti e the Self with Nature or Prak me Lilli011 °f th an with a blind rria l' 4, riti • ation Of a blind man were deserted 6 irr,, lame m filarl and a in a forest. They agreed # ' th, 1 iiC ZSSOC1 n. A 1 between fellow-travellers . them the duties of walking and of se_. livid, ,ing. , ,0 ,, . 't man mounted himself on the shoulders of th ih, lame — e hl; man and directed the blind man. The blind rnan Iv nn as abir his route by the directions of his friend. D ' to pursue iz,v,.r the Self is like the lame man. The faculty of seein'. isno,the Self, not that of moving. The faculty of moving) 'buL not of seeing, is in Prakriti. Prakriti is like the blind mail' The lame man and the blind man separated when they reached their destination. Even so, Prakriti, havin effected the liberation of the Self, ceases to act.The SF': obtains Kaivalya or the final beatitude. Consequently their respective purposes being effected, the connectiOr, between them terminates. The Self attains liberation b'. knowledge of Prakriti. Prakriti's performances are solely for the benefit and enjoyment of the Self. Prakriti takes hold of the hand o: the Self and shows it the whole show of the universe, and makes it enjoy everything which this world can give, anc, lastly helps it in its liberation. In truth, the Self ' does it migrate, t e is neither bound nor released, nc:- beings is bound, . gra e, but Nature alone in relation to various oun , is released, and migrates. AS a danci the spectators dancing girl, having exhibited herself on the stage to th ceases to function A/he , stops dancing, so also Nato to the Purusha or anifes' n she has made herself m , Prakriti uth r the Self. Nothing is more modes , t thal` when she be be' seen by th comes conscious that she has i the Puru 1-, to the gaze She e hers e does not again expos saze of the Pu rusha,

परिचय || Introduction

In the context of ancient Indian philosophies, Samkhya philosophy is based on systematic enumeration and rational examination. It's philosophical treatises also influenced the development of various theories of Hindu ethics. Samkhya || साङ्ख्य is, thus, depending on the context, means "to reckon, count, enumerate, calculate, deliberate, reason, reasoning by numeric enumeration, relating to number, rational".

- Samkhya is strongly dualist accepting the roles of प्रकृति || Prakriti and पुरुष || Purusha in the Creation of this Universe.

- Samkhya siddhanta accepts that enumeration of truth can be done by using three of six accepted प्रमाणाः || pramanas (proofs).

- The Trigunas exist in all life forms in different proportions.

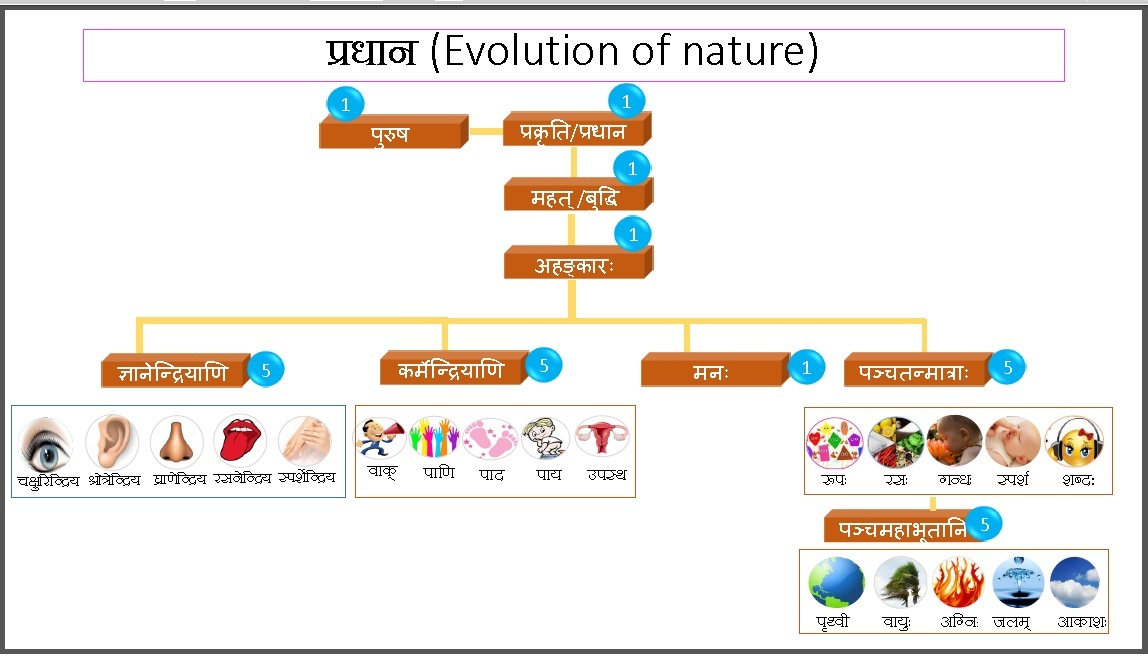

- It 'enumerates' twenty five Tattvas or true principles; and its chief object is to effect the final emancipation of the twenty-fifth Tattva, i.e. the purusha or soul. The evolutionary process involves Pradhana (Prakruti), Purusha, Mahat (Buddhi), Ahankaraara, Pancha Jnanendriyas, Pancha Karmendriyas, Panchatanmatras, Panchabhutas and Manas

- Samkhya denies that reaching God is the goal of life.

- While the Samkhya school considers the Vedas as a reliable source of knowledge, a key difference between Samkhya and Yoga schools, state scholars, is that Yoga school accepts a "personal, yet essentially inactive, deity" or "personal god".

- The existence of God or supreme being is not directly asserted, nor considered very relevant by the Samkhya philosophers.

- Samkhya school considers मोक्ष || moksha as a natural quest of every soul.

Founder - Kapila Maharshi

Sage Kapila is traditionally credited as a founder of the Samkhya school.

Kapila appears in ऋग्वेद || Rigveda, but context suggests that the word means "reddish brown color". Both Kapila as a "seer" and the term Samkhya appear in hymns of section 5.2 in Shvetashvatara Upanishad (~300 BCE), suggesting Kapila's and Samkhya philosophy's origins may predate it.

Numerous other ancient Indian texts mention Kapila,

- Baudhayana Grhyasutra in chapter IV.16.1 describes a system of rules for ascetic life credited to Kapila, called Kapila Sannyasa Vidha.

- A 6th century CE Chinese translation and other texts consistently state Kapila as an ascetic and the founder of the school, mention Asuri as the inheritor of the teaching, and a much later scholar named Pancasikha as the scholar who systematized it and then helped widely disseminate its ideas. Isvarakrsna is identified in these texts as the one who summarized and simplified Samkhya theories of Pancasikha, many centuries later (roughly 4th or 5th century CE), in the form that was then translated into Chinese by Paramartha in the 6th century CE.

- Bhagavadgeeta discusses the Samkhya yoga.

Origin of Samkhya

Some 19th and 20th century scholars suggested that Samkhya may have non-Vedic origins and that the Samkhya philosophy is, in its essence, not only atheistic but also inimical to the Veda (Richard Garbe). While Dandekar, similarly wrote in 1968, "The origin of the Samkhya is to be traced to the pre-Vedic non-Aryan thought complex". Disagreeing with it Arthur Keith, for example in 1925, stated, "Samkhya owes its origin to the Vedic-Upanisadic-epic heritage is quite evident," and "Samkhya is most naturally derived out of the speculations in the Vedas, Brahmanas and the Upanishads". Many other scholars have discussed the probable reasons for the origin of this school of thought, though none of them can be proved or accepted as totally factual.

Between 1938 and 1969, two previously unknown manuscript editions of Yuktidipika were discovered and published. युक्तिदिपिका || Yuktidipika is an ancient review and has emerged as the most important commentary on Samkhyakarika – itself an ancient key text of the Samkhya school. This discovery and recent scholarship(Paul Hacker and others) suggests Samkhya was well established and existed vedic period in ancient India. However, almost nothing is preserved about the centuries when these ancient Samkhya scholars lived.

Larson, Bhattacharya and Potter state that the newly discovered literature hints, but does not conclusively prove, that Samkhya may be the oldest school of Indian philosophy, one that evolved over time and influenced major schools, as well as Buddhism and Jainism. These scholars place the earliest references to Samkhya ideas in the Vedic period literature of India (~1500 BCE to ~400 BCE).

Samkhya Siddhantam

Pramanas

It is based on systematic enumeration and using the three of six प्रमाणाः pramanas (proofs) as the only reliable means of gaining knowledge. These include

- प्रत्यक्षप्रमाणाः || pratyaksha-pramana (perception),

- अनुमानप्रमाणाः anumana-pramana (inference) and

- शब्दप्रमाणाः sabda-pramana (aptavacana, word/testimony of reliable sources).

Dvaita Tatvam

Samkhya is strongly द्वैत || Dvaita (dualist) in its approach. Samkhya philosophy regards the universe as consisting of two realities; पुरुष || Purusha (consciousness) and प्रकृति || Prakrti (matter). जीव || Jiva (a living being) is that state in which Purusha is bonded to Prakriti. This fusion, state the Samkhya scholars, led to the emergence of बुद्धि || buddhi (intellect) and अहङ्कार || Ahankara (ego consciousness). The universe is described by this school as one created by purusa-prakrti entities infused with various permutations and combinations of variously enumerated elements, senses, feelings, activity and mind. During the state of imbalance, one of more constituents overwhelm the others, creating a form of bondage, particularly of the mind. The end of this imbalance, bondage is called कैवल्य || kaivalya (liberation), by the Samkhya school.

Trigunas

Samkhya is known for its theory of गुण || gunas (qualities, innate tendencies). Guna, it states, are of three types: Satva, Rajas and Tamas.

- सत्त्व || Sattva being good, compassionate, illuminating, positive, and constructive

- रजस || Rajas is one of activity, chaotic, passion, impulsive, potentially good or bad

- तमस || Tamas being the quality of darkness, ignorance, destructive, lethargic, negative

Everything, all life forms and human beings, state Samkhya scholars, have these three gunas, but in different proportions.

Twenty Five Tattvas

It 'enumerates' twenty five Tattvas or true principles.

Moksha for the Purusha

Samkhya school considers moksha as a natural quest of every soul.

The Samkhya school considers perception, inference and reliable testimony as three reliable means to knowledge. Samkhya considered प्रत्यक्ष || Pratyaksha or दर्शनम् || Darsanam (direct sense of eyes and perception), अनुमान || Anumana (inference), and शब्द || Sabda or अप्तवचन ||| Aptavacana (verbal testimony of the sages or shastras) to be the only valid means of knowledge or pramana. Unlike few other schools, Samkhya did not consider the following three pramanas as epistemically proper: उपमान || Upamana (comparison and analogy), अर्थापत्ति || Arthaapatti (postulation, deriving from circumstances) or अनुपलब्दि || Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof).

Evolution in Samkhya is thought to be purposeful. The two primary purposes of evolution of prakruti are the enjoyment and the liberation of Purusha. The 23 evolutes of prakuti are categorized as follows:

The Supreme Good is moksha which consists in the permanent impossibility of the incidence of pain... in the realisation of the Self as Self pure and simple.

—Samkhyakarika I.3 Samkhya school considers moksha as a natural quest of every soul. The Samkhyakarika states,

As the unconscious milk functions for the sake of nourishment of the calf, so the Prakriti functions for the sake of moksha of the spirit.

—Samkhya karika, Verse 57 Samkhya regards अविद्या || avidya (ignorance) as the root cause of suffering and संसार || Samsara (bondage). Samkhya states that the way out of this suffering is through विवेक || viveka (knowledge). मोक्ष || Moksha (liberation), states Samkhya school, results from knowing the difference between prakruti (avyakta-vyakta) and purusha (jña).

Purusha, the eternal pure consciousness, due to ignorance, identifies itself with products of prakrti such as बुद्धि || buddhi (intellect) and अहङ्कार || ahamkara (ego). This results in endless transmigration and suffering. However, once the realization arises that Purusha is distinct from prakrti, is more than empirical ego, and that Purusha is deepest conscious self within, the Self gains कैवल्य || kaivalya (isolation) and मोक्ष || moksha (liberation).

Other forms of Samkhya teach that Moksha is attained by one's own development of the higher faculties of discrimination achieved by meditation and other yogic practices. Moksha is described by Samkhya scholars as a state of liberation, where Sattva guna predominates.

Emergence as a distinct philosophy

The early texts of the Vedic period contain references to elements of Samkhya philosophy. However, the Samkhya ideas had not distilled and congealed into a distinct, complete philosophy. Sometime about the 5th century BCE, Samkhya thought from various sources started coalescing into a distinct, complete philosophy, according to some scholars.

- In the beginning this was Self alone, in the shape of a person (purusha). He looking around saw nothing but his Self (Atman). He first said, "This is I", therefore he became I by name. (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.1)

- Philosophical texts such as the Katha Upanishad in verses 3.10-13 and 6.7-11 describe a well defined concept of Purusha and other concepts of Samkhya.

- The Shvetashvatara Upanishad in chapter 6.13 describes Samkhya with Yoga philosophy.

- Bhagavad Gita in Chap 2 provides textual evidence of Samkhya terminology and concepts.

- Katha Upanishad conceives the Purusha (cosmic spirit, consciousness) as same as the individual soul (Atman, Self).

- The Mokshadharma chapter of Shanti Parva (Book of Peace) in the Mahabharata epic, composed between 400 BCE to 400 CE, explains Samkhya ideas along with other extant philosophies, and then lists numerous scholars in recognition of their philosophical contributions to various Indian traditions, and therein at least three Samkhya scholars can be recognized – Kapila, Asuri and Pancasikha.

- The 12th chapter of the Buddhist text Buddhacarita suggests Samkhya philosophical tools of reliable reasoning were well formed by about 5th century BCE.

Samkhya and Yoga are mentioned together for first time in chapter 6.13 of the Shvetashvatra Upanishad, as सांख्य योग अधिगम्य || samkhya-yoga-adhigamya (literally, "to be understood by proper reasoning and spiritual discipline"). Bhagavad Gita identifies Samkhya with understanding or knowledge. The three gunas are also mentioned in the Gita, though they are not used in the same sense as in classical Samkhya. The Gita integrates Samkhya thought with the भक्ति || bhakti (devotion) of theistic schools and the impersonal Brahman of Vedanta.

Vedic and Upanishad Influences

The ideas that were developed and assimilated into the classical Samkhya text, the karikas, are visible in earlier Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. The earliest mention of dualism is in the Rigveda, नासदीय सूक्त || Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn of non-Eternity, origin of universe): Rigveda 10.129 hymn is one of the roots of the Samkhya.

—Rigveda 1.164.20 - 1.164.22 The emphasis of duality between सत् || sat (existence) and असत् || asat (non-existence) in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rigveda is similar to the व्यक्त-अव्यक्त || vyakta–avyakta (manifest–unmanifest) polarity in Samkhya. The hymns about Purusha may also have influenced Samkhya. The Samkhya notion of buddhi or महत् || mahat is similar to the notion of हिरण्यगर्भ || hiranyagarbha, which appears in both the Rigveda and the Shvetashvatara Upanishad.

Higher than the senses, stand the objects of senses. Higher than objects of senses, stands mind. Higher than mind, stands intellect. Higher than intellect, stands the great self. Higher than the great self, stands Avyaktam. Higher than Avyaktam, stands Purusha. Higher than this, there is nothing. He is the final goal and the highest point. In all beings, dwells this Purusha, as आत्मन || Atman (soul), invisible, concealed. He is only seen by the keenest thought, by the sublest of those thinkers who see into the subtle.

—Katha Upanishad 3.10-13. The oldest of the major Upanishads (c. 900–600 BCE) contain speculations along the lines of classical Samkhya philosophy.

The concept of ahamkara in Samkhya can be traced back to the notion of ahamkara in chapters 1.2 and 1.4 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and chapter 7.25 of the Chandogya Upanishad.

Satkaryavada, the theory of causation in Samkhya, can be traced to the verses in sixth chapter which emphasize the primacy of सत् || sat (being) and describe creation from it. The idea that the three gunas or attributes influence creation is found in both Chandogya and Shvetashvatara Upanishads.

Upanishadic sages Yajnavalkya and Uddalaka Aruni developed the idea that pure consciousness was the innermost essence of a human being. The purusha of Samkhya could have evolved from this idea. The enumeration of tattvas in Samkhya is also found in Taittiriya Upanishad, Aitareya Upanishad and Yajnavalkya–Maitri sambhashanam in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

This declared to you is the Yoga of the wisdom of Samkhya. Hear, now, of the integrated wisdom with which, Partha, you will cast off the bonds of karma.

—Bhagavad Gita 2.39

Other Textual Material

The earliest surviving authoritative text on classical Samkhya philosophy is the Samkhya Karika (c. 200 CE or 350–450 CE) of Isvarak???a. There were probably other texts in early centuries CE, however none of them are available today.

Isvarak???a in his Karika describes a succession of the disciples from Kapila, through Asuri and Pañcasikha to himself. The text also refers to an earlier work of Samkhya philosophy called ?a??itantra (science of sixty topics) which is now lost. The text was imported and translated into Chinese about the middle of the 6th century CE. The records of Al Biruni, the Persian visitor to India in the early 11th century, suggests Samkhyakarika was an established and definitive text in India in his times.

—Samkhya Karika Verse 4–6, The most popular commentary on the Samkhyakarikia was the Gau?apada Bha?ya attributed to Gau?apada, the proponent of Advaita Vedanta school of philosophy. Richard King, Professor of Religious Studies, thinks it is unlikely that Gau?apada could have authored both texts, given the differences between the two philosophies. Other important commentaries on the karika were Yuktidipika (c. 6th century CE) and Vacaspati’s Sankhyatattvakaumudi (c. 10th century CE).

The Sankhyapravacana Sutra (c. 14th century CE) renewed interest in Samkhya in the medieval era. It is considered the second most important work of Samkhya after the karika. Commentaries on this text were written by Anirruddha (Sa?khyasutrav?tti, c. 15th century CE), Vijñanabhik?u (Sa?khyapravacanabha?ya, c. 16th century CE), Mahadeva (v?ttisara, c. 17th century CE) and Nagesa (Laghusa?khyasutrav?tti). According to Surendranath Dasgupta, scholar of Indian philosophy, Charaka Samhita, an ancient Indian medical treatise, also contains thoughts from an early Samkhya school.

The 13th century text Sarvadarsanasangraha contains 16 chapters, each devoted to a separate school of Indian philosophy. The 13th chapter in this book contains a description of the Samkhya philosophy.

Lost Textual References

In his Studies in Samkhya Philosophy, K.C. Bhattacharya writes:

Much of Samkhya literature appears to have been lost, and there seems to be no continuity of tradition from ancient times to the age of the commentators...The interpretation of all ancient systems requires a constructive effort; but, while in the case of some systems where we have a large volume of literature and a continuity of tradition, the construction is mainly of the nature of translation of ideas into modern concepts, here in Samkhya the construction at many places involves supplying of missing links from one's imagination. It is risky work, but unless one does it one cannot be said to understand Samkhya as a philosophy. It is a task that one is obliged to undertake. It is a fascinating task because Samkhya is a bold constructive philosophy.