Difference between revisions of "Inference and its classification (अनुमानं तस्य प्रकाराश्च)"

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

=== Svartha and Parartha (स्वार्थपरार्थश्च) === | === Svartha and Parartha (स्वार्थपरार्थश्च) === | ||

| + | [[File:Swarthanumana.png|thumb|250x250px|alt=|Svarthanumana]] | ||

An inference is called svartha when it aims at the knowledge of an unperceived object on the part of a man who employs that inference. In this kind of inference a man seeks only to reach the conclusion for himself by relating it to the major and minor premises. An example of this is when a man first notices a mass of smoke on a hill and then recalls that smoke and fire have a universal relationship, leading him to conclude that there is fire there. | An inference is called svartha when it aims at the knowledge of an unperceived object on the part of a man who employs that inference. In this kind of inference a man seeks only to reach the conclusion for himself by relating it to the major and minor premises. An example of this is when a man first notices a mass of smoke on a hill and then recalls that smoke and fire have a universal relationship, leading him to conclude that there is fire there. | ||

| − | + | ||

Whereas, an inference is considered parartha when it is intended to convince others of the validity of the conclusion. In this inference there is a justification of the conclusion through a justification of the middle term that leads to it. It is here specifically pointed out that the same middle term, which is universally related to the major is also present in the minor term. The conclusion is thus found to follow necessarily from a synthesis of the major and minor premises. This synthesis is embodied in a third premise which relates the minor, middle and major terms of the inference. A parartha anumana is illustrated when a man, having inferred the existence of fire in a hill lays it down as a thesis and proves it as a conclusion following from the major and minor premises and their combination into a third premise. | Whereas, an inference is considered parartha when it is intended to convince others of the validity of the conclusion. In this inference there is a justification of the conclusion through a justification of the middle term that leads to it. It is here specifically pointed out that the same middle term, which is universally related to the major is also present in the minor term. The conclusion is thus found to follow necessarily from a synthesis of the major and minor premises. This synthesis is embodied in a third premise which relates the minor, middle and major terms of the inference. A parartha anumana is illustrated when a man, having inferred the existence of fire in a hill lays it down as a thesis and proves it as a conclusion following from the major and minor premises and their combination into a third premise. | ||

| − | === Purvavat, Sheshavat and Samanyatodrshta (पूर्ववत् शेषवत् सामान्यतोदृष्ट) === | + | ===Purvavat, Sheshavat and Samanyatodrshta (पूर्ववत् शेषवत् सामान्यतोदृष्ट)=== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[File:Karnena Karyanumanam.jpg|thumb|209x209px|Purvavat Anumana:- Infering the effect through the cause. | [[File:Karnena Karyanumanam.jpg|thumb|209x209px|Purvavat Anumana:- Infering the effect through the cause. | ||

| − | Image Courtesy:- Monali V. Chandelkar (Image created using Chatgpt)]] | + | Image Courtesy:- Monali V. Chandelkar (Image created using Chatgpt)]]In the Nyaya-Sutra inference is distinguished into three kinds, namely, purvavat, sheshavat and samanyatodrshta. There are different views with regard to the nature of these inferences. According to one view, a purvavat inference is that in which we infer the unperceived effect from a perceived cause. Here the linga or the middle term is related to the sadhya or the major term as its cause and is, therefore, antecedent to it. In this inference we pass from the knowledge of the antecedent cause to that of the consequent effect. This is illustrated when from the presence of dark heavy clouds in the sky we infer that there will be rainfall. A sheshavat inference is that in which we infer the unperceived cause from a perceived effect. Here the middle term is related as an effect to the major term and is, therefore, consequent to it In this inference we pass from the knowledge of the effect-phenomenon to that of the antecedent causal phenomenon. This is illustrated in the inference of previous rain from the rise of the water in the river and its swift muddy current. It will be observed here that in both purvavat and sheshavat inferences the vyapti or the universal relation between the major and middle terms is a uniform relation of causality between them. These in |

| + | ===Kevalanvayi, Kevala-vyatireki and Anvaya-vyatireki (केवलान्वयी, केवल व्यतिरेकी, अन्वय व्यतिरेकी)=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Inferences have been categorized into three types based on the procedures used to establish vyapti or a universal relation between the hetu (middle term) and sadhya (major term): Kevalanvayi, Kevala-vyatireki, and Anvaya-vyatireki. An inference is called kevalanvayi when vyapti between hetu and sadhya is established through only anvaya (presence) and there is no possible instance of Vyatireka (negative). For example, | ||

| + | |||

| + | All knowable objects are nameable, The bike is a knowable object, therefore the bike is nameable. Here, | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Paksha: Bike | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Hetu: It is knowable | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Sadhya: It is nameable | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Vyapti: All knowable objects are nameable | ||

| + | |||

| + | With accordance to this universal affirmative proposition We can't have a real universal where statement like "No unnameable object is knowable" is possible, since we can't point to or name anything that is unnameable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Kevala vyatireki the understanding of vyapti is attained solely through the way of agreement in vyatireka. For Instance, when one refers 'earth is different from non earth' (other elements) because it has smell. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | sadhya and hetu are . it depends on a vyapti between the absence of sadhya and that of hetu.The understanding of vyapti is attained solely through the way of agreement in vyatireka, as there is no positive instance of agreement in presence between hetu and sadhya, other from the paksha. For Example, | ||

| + | |||

| + | What is not different from the other elements has no smell, the earth has smell, therefore the earth is different from the other elements. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Paksha: Earth | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hetu: Earth has smell | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sadhya: Earth is different from other elements | ||

| + | |||

| + | Vyapti: What is not different from the other elements has no smell | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 17:47, 20 June 2025

Knowledge and its two types

Understanding the four pramanas

components of inference

Types of inference

Introduction ॥ परिचयः

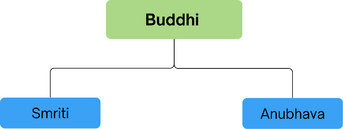

Nyayashastra explores the practical methods for achieving authentic knowledge of metaphysical truths and the principles of knowing. It is primarily concerned with the conditions of valid thought and the means of acquiring a true knowledge of objects where tarkashastra defines Knowledge as of two types: Smriti (Remembrance) and Anubhava (Experience).

Smriti and Anubhava ॥ स्मृतिअनुभवश्च

Anubhava contains presentational knowledge about objects, which we see as being imparted to us. It is unique in nature and does not reproduce prior knowledge about objects. On the other hand, smriti is not a representation of different things; rather, it is a reproduction of events that have occurred in the past. for example, Hari saw his father sowing a mango seed, that action happening in front of him is his anubhava which while recalling that same activity after few days, will become smriti. There are two kinds of anubhava: Yathartha anubhava (the anubhava which correlates with reality is called as yathartha anubhava) for example, if we see a dog on the road and cognize ‘this is a dog’ and if this cognition corresponds to the actual presence of a dog, and your pratyaksha (sense perception) was not defective, then it is yathartha anubhava. The second type of anubhava is ayathartha anubhava (the one which does not correlate with reality). For example you see a long black colored thing on ground and think 'this is a snake’ but in reality, it is a rope, not a snake. Here the cognition that this is a snake is not in accordance with the actual object. The pratyaksha (sense perception) is defective, often due to conditions like poor lighting, distance, or similarity in appearance. Therefore, it is an ayathartha anubhava. Of these the former is called pramā and includes all cases of true presentational knowledge of objects.

There are four different types of prama, according to Nyaya: pratyaksha, anumiti, upamiti, shabda. and there are four pramanas, or tools, to comprehend this prama knowledge: pratyaksha, anumana, upamana and shabda.

Understanding the four pramanas ॥ चत्वारि प्रमाणानि

Pratyksha pramana- In Tarkasangraha Pratyksha pramana is defined as

इन्द्रियार्थसन्निकर्षजन्यम् ज्ञानम् प्रत्यक्षम् | Indriyārthasannikarṣajanyam jñānam pratyakṣam

In simple terms pratyksha pramana is the valid knowledge produced by the contact of an object with a sense organ. pratyaksha as In Navya-Nyāya (founded by Gangesha Upādhyāya in Tattvacintāmaṇi), is redefined and refined using a highly technical and precise logical-epistemological framework.

Anumana pramana- Anumana means such knowledge as follows some other knowledge. It is the knowledge of an object due to previous knowledge of some sign.

Upamana pramana - The word upamana is derived from the words upa, meaning sādṛśya or similarity, and mana, meaning cognition. Hence, upamana deritavely means the knowledge of the similarity between two things. As a pramāṇa, upamāna is the source of our knowledge about the relation between a word and its denotation. For example, if someone does not know what a metro is, they may be told by a resident that it is like a train. The next time that person sees such a vehicle in the city, he knows that it is the metro.

Shabda pramana- Shabda literally means verbal knowledge. It is the knowledge of objects derived from words or sentences. All verbal knowledge, however, is not valid; hence, shabda, as a pramana, is defined in the Nyaya as valid verbal testimony. It consists of the assertion of a trustworthy person. A verbal statement is valid when it comes from a person who knows the truth and speaks the truth about anything for the guidance of the other person. आप्तवाक्यम् शब्दः । āptavākyam śabdaḥ

Anumana and its components ॥ अनुमानं तस्य घटकाश्च

All systems of Indian Philosophy agree in holding that anumana is a process of arriving at truth not by direct observation but by means of the knowledge of Vyapti or a universal relation between two things.

दृष्टादृष्टसामान्यात् अनुमानम्

Classical example of anumana: There is fire on the mountain because there is smoke; where there is smoke, there is fire.

Components of inference:

Paksha- Paksha is the subject where we establish something. Paksha is the component of the inference in relation to which the inference is made. For example, the mountain in the above example is the paksha because there has been anumana regarding the mountain. Paksha is to be perceived but not inferred.

Sadhya- Sadhya is the object of inference; it is not perceived. Whatever is proved in relation to the paksha is called the sadhya. Fire is sadhya because the existence of fire in the mountain has been proved.

Hetu- By which it is said to be the sadhya in the paksha, it is called the hetu. In the above example, smoke is hetu because, seeing the smoke, it is inferred that there is a fire on the mountain.

Vyapti- Every inference is logically dependent on the knowledge of vyapti. It implies a correlation between two facts, of which one is pervaded (vyapya) and the other is pervades (vyapaka). A fact is said to pervade another when it always accompanies the other. Contrary, a fact is said to be pervaded by another when it is always accompanied by the other.

Udaharana- Drishtant is a well-known instructive example that uses analogies to clarify an idea. It is frequently employed outside of formal inference, such as in disputes, scripture, or instruction. Its objective is to clarify an idea or help the audience understand something abstract by using something concrete or familiar.

Difference between anumana and pratyaksha

Perception is limited to the present because perception is done through the sense. the knowledge of the thing which is beyond the reach of the senses is not obtained from perception. But

Types of inference ॥ अनुमानस्य प्रकाराः

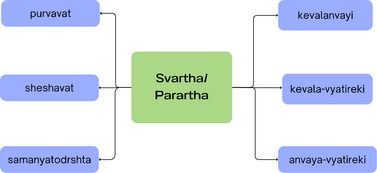

An inference in Indian logic is a combined deductive and inductive process comprising at least three categorical propositions. We therefore do not classify inferences into deductive and inductive, direct and intermediary, syllogistic and non-syllogistic, pure and mixed. The naiyayikas give us three different classifications of inference. According to the first, inference is of two kinds, namely, svartha and parartha. According to another classification, inference is said to be of three kinds, namely, purvavat, sheshavat, and samanyatodrsta. This classification has reference to the nature of the vyapti or the universal relation between the middle and major terms of inference. Purvavat and sheshavat inferences are based on causal uniformity, while samanyatodrshta is based on non-causal uniformity. According to a third classification, inference is distinguished into kevalanvayi, kevala-vyatireki and anvaya-vyatireki. This classification is more logical in as much as it depends on the nature of the induction by which we get the knowledge of vyapti or the universal proposition involved in reference.

Svartha and Parartha (स्वार्थपरार्थश्च)

An inference is called svartha when it aims at the knowledge of an unperceived object on the part of a man who employs that inference. In this kind of inference a man seeks only to reach the conclusion for himself by relating it to the major and minor premises. An example of this is when a man first notices a mass of smoke on a hill and then recalls that smoke and fire have a universal relationship, leading him to conclude that there is fire there.

Whereas, an inference is considered parartha when it is intended to convince others of the validity of the conclusion. In this inference there is a justification of the conclusion through a justification of the middle term that leads to it. It is here specifically pointed out that the same middle term, which is universally related to the major is also present in the minor term. The conclusion is thus found to follow necessarily from a synthesis of the major and minor premises. This synthesis is embodied in a third premise which relates the minor, middle and major terms of the inference. A parartha anumana is illustrated when a man, having inferred the existence of fire in a hill lays it down as a thesis and proves it as a conclusion following from the major and minor premises and their combination into a third premise.

Purvavat, Sheshavat and Samanyatodrshta (पूर्ववत् शेषवत् सामान्यतोदृष्ट)

In the Nyaya-Sutra inference is distinguished into three kinds, namely, purvavat, sheshavat and samanyatodrshta. There are different views with regard to the nature of these inferences. According to one view, a purvavat inference is that in which we infer the unperceived effect from a perceived cause. Here the linga or the middle term is related to the sadhya or the major term as its cause and is, therefore, antecedent to it. In this inference we pass from the knowledge of the antecedent cause to that of the consequent effect. This is illustrated when from the presence of dark heavy clouds in the sky we infer that there will be rainfall. A sheshavat inference is that in which we infer the unperceived cause from a perceived effect. Here the middle term is related as an effect to the major term and is, therefore, consequent to it In this inference we pass from the knowledge of the effect-phenomenon to that of the antecedent causal phenomenon. This is illustrated in the inference of previous rain from the rise of the water in the river and its swift muddy current. It will be observed here that in both purvavat and sheshavat inferences the vyapti or the universal relation between the major and middle terms is a uniform relation of causality between them. These in

Kevalanvayi, Kevala-vyatireki and Anvaya-vyatireki (केवलान्वयी, केवल व्यतिरेकी, अन्वय व्यतिरेकी)

Inferences have been categorized into three types based on the procedures used to establish vyapti or a universal relation between the hetu (middle term) and sadhya (major term): Kevalanvayi, Kevala-vyatireki, and Anvaya-vyatireki. An inference is called kevalanvayi when vyapti between hetu and sadhya is established through only anvaya (presence) and there is no possible instance of Vyatireka (negative). For example,

All knowable objects are nameable, The bike is a knowable object, therefore the bike is nameable. Here,

- Paksha: Bike

- Hetu: It is knowable

- Sadhya: It is nameable

- Vyapti: All knowable objects are nameable

With accordance to this universal affirmative proposition We can't have a real universal where statement like "No unnameable object is knowable" is possible, since we can't point to or name anything that is unnameable.

In Kevala vyatireki the understanding of vyapti is attained solely through the way of agreement in vyatireka. For Instance, when one refers 'earth is different from non earth' (other elements) because it has smell.

sadhya and hetu are . it depends on a vyapti between the absence of sadhya and that of hetu.The understanding of vyapti is attained solely through the way of agreement in vyatireka, as there is no positive instance of agreement in presence between hetu and sadhya, other from the paksha. For Example,

What is not different from the other elements has no smell, the earth has smell, therefore the earth is different from the other elements.

Paksha: Earth

Hetu: Earth has smell

Sadhya: Earth is different from other elements

Vyapti: What is not different from the other elements has no smell

Book references

Tarkasangrah of Annambhatta https://archive.org/details/TarkasangrahaOfAnnambhattaVNJha