Difference between revisions of "Shiksha (शिक्षा)"

(Removed Template) |

(→Shiksha Granthas: added table) |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Shiksha (Samskrit: शिक्षा) is a shastra pertaining to pronunciation and accent which has a major role in the preservation of the vaidika mantras; as such it is insufficiently expressed as phonetics.<ref>All About Hinduism, Swami Sivananda, Page 34</ref> In this context it refers to one of the six [[Shad Vedangas (षड्वेदाङ्गानि)|Vedangas]], or limbs of Vedic studies, the others being [[Vyakarana Vedanga (व्याकरणवेदाङ्गम्)|Vyākaraṇam]] (Grammar), Chandas (Prosody), Niruktam (Semantics and Thesaurus), [[Vedanga Jyotisha (वेदाङ्गज्योतिषम्)|Jyotiṣam]] (Astrology) and [[Kalpa Vedanga (कल्पवेदाङ्गम्)|Kalpa]] (Practice of Rites). It has an important place in the Vidyasthanas and hence study of this shastra is a prerequisite for Vyakarana. | |

| − | + | [[File:Shiksha.png|thumb|600x600px|'''Articulation of Sounds from Throat, Nose and Mouth''' Courtesy: Book "Sarwang" Published by Adivasi Lok Kala Evam Boli Vikas Academy, Madhya Pradesh Sanskriti Parishad]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == परिचयः ॥ Introduction == | |

| + | Shiksha is considered as the nose (घ्राणम् - ghrāṇam) of Vedapuruṣa (knowledge personified) as described in Mundakopanishad (1.1.15). Unlike other later day languages, pronunciation is of utmost importance in Samskrit. Different speech organs, places for different letters, the efforts, the accents, quantity, pitch, stress, melody, process of how letters are produced, the virtues and vices of pronunciation, the problem with mispronunciation etc. are discussed in this science of pronunciation dealt with, in the [[Shad Vedangas (षड्वेदाङ्गानि)|Shad Vedangas]]. The literature pertaining to Vedanga Shiksa is classified into Pratishakhyas and Shiksagranthas. | ||

| − | + | Each ancient vaidika parampara survived through millenia as they developed pronunciation and the testimony to this is fact, are the surviving texts, namely Pratishakyas. It is the effect of this knowledge that the utterance of vaidika mantras have been unchanged in each parampara. The Paniniya-Shiksha and Naradiya-Shiksha are examples of extant ancient manuscripts of this field of Vedic studies. | |

| − | + | Phonetics (in Modern Linguistics) is a rough translation of Śikṣā. The latter deals with many issues related to pronunciation unlike the former word where only a few linguistic aspects are discussed. The term Śikṣā literally means – the one that trains pronunciation etc. of letters. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ==व्युत्पत्तिः ॥ Etymology== |

| + | The word Shiksha (शिक्षा । Śikṣā) has been derived from the dhatu शक् in the meaning, 'शक्तौ to be able' - शक्तुं शक्तो भवितुमिच्छा शिक्षा is the vyutpatti that applies here according to Pt. Ramprasad Tripathi.<ref name=":3">Pt. Ramprasad Tripathi. (1989) ''Siksasamgraha of Yajnavalkya and Others.'' Varanasi: Sampurnanand Sanskrit University. </ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The roots of Shiksha can be traced to [[Rigveda (ऋग्वेदः)|Rigveda]] which dedicates two hymns 10.125 and 10.71 to revere sound as a deity, and links the development of thought to the development of speech. Taittiriya Upanishad, in Shikshavalli, contains one of the earliest description of Shiksha as follows,<blockquote>शीक्षां व्याख्यास्यामः। वर्णस्स्वरः। मात्रा बलम्। साम सन्तानः। इत्युक्तश्शिक्षाध्यायः ॥ (Tait. Upan. Shik. 2)<ref>Taittriya Upanishad ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%88%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A4%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B0%E0%A5%80%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%8D/%E0%A4%B6%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4% Shikshavalli Anuvaka 2])</ref></blockquote>Now, we will clearly state about Shiksha (phonetics). There are six aspects to be discussed in Shiksha: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | वर्णः । varna (sounds), स्वरः । svara (accents), मात्रा । matra (short/long vowel pronunciation), बलम् । bala (the force), साम । saama (even articulation) and सन्तानः। santana (continuity in recitation) - this is termed (studied) the chapter of Shiksha.<ref name=":5" /> | |

| − | + | Therefore, the aim of Shiksha is to teach the pronunciation of Varna, which is pronounced from which place (throat. lips etc), what effort is required in it, in what form they are divided, how many places and efforts are there, along with the physiology of how the body and air are related to Varna, its changes in form, the number of vowels and consonants and their pronunciation.<ref name=":6">Dvivedi, Kapil Dev. (2000) ''Vaidika Sahitya evam Samskrti (Vedic Literature and Culture).'' Varanasi: Vishvavidyalaya Prakashan. (Pages )</ref> | |

| − | == | + | == Evolution of Linguistic Concepts == |

| − | + | The formal treatment of pronunciation and related linguistic aspects in ancient India begin with the texts called Pratisakhyas and Shikshas granthas which are said to be much later than the Vedas. The preformal speculations concerning sounds in particular and language in general are found throughout the Vedic literature. In this section we trace the evolution of linguistic units and the various components that play a role in the development of a language.<ref name=":5">Deshpande, Madhav M. ''[https://www.academia.edu/1306429/Ancient_Indian_phonetics Ancient Indian Phonetics]'' Ann Arbor: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, The Univ. of Michigan. </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === अक्षरम् ॥ Akshara (Syllable) === | |

| + | Among the old preformal conceptions of language and linguistic units, are the notions of [[Chandas (छन्दस्)|chandas]] or meters, the metrical feet, words and syllables, along with very few technical terms found in later day texts. Rigveda refers to different meters by name, e.g. Gayatri, Brhati, and Trishtubh. Vaidika chandas has two prominent features viz., fixed number of पद-s (padas or metrical foot) in a mantra/shloka and fixed number of syllables in a pada. The word, पद (pada), occasionally also meant a word or a name. However, in later day classical samskrit, the word पद (pada) referred primarily to words, and a new, though related, term, पाद (paada), began to be used for metrical foot. | ||

| − | + | Another important term, अक्षरम् (akshara) or syllable is also found widely used in the vedas. Presently, the widely used common term 'Varna' is not found in the vedic literature. In the Rigveda, it appears that a syllable formed the very basic unit or measure of language, and recognizing the divine nature of language, everything ultimately rests in the divine अक्षरम् (akshara). Rigveda, is crucial to our understanding of the earliest notions of "linguistic units":<blockquote>गा॒य॒त्रेण॒ प्रति॑ मिमीते अ॒र्कम॒र्केण॒ साम॒ त्रैष्टु॑भेन वा॒कम् । वा॒केन॑ वा॒कं द्वि॒पदा॒ चतु॑ष्पदा॒ ऽक्षरे॑ण मिमते स॒प्त वाणी॑: ॥२४॥ (Rig. Veda. 1.164.24)<ref>Rig Veda ([http://vedicheritage.gov.in/samhitas/rigveda/shakala-samhita/rigveda-shakala-samhitas-mandal-01-sukta-164/ Mandala 1])</ref></blockquote>Summary: With the Gayatri foot, he (the vedic seer) measures the Arka, with the Arka the Saman, with the Trishtubh foot the Vaka; with the two-foot and four-foot Vaka the recitation; with the syllable the seven voices. | |

| − | + | It seems that the attention of the ancient vedic seers was focused primarily on those linguistic units which were numerically fixed in some sense. Thus, the smallest countable unit is an Akshara. For example, there are eight syllables in Gayatri chandas. It may be noted that focus was on the linguistic units fixed numerically but may contain any number of individual sounds. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === वर्णः ॥ Varna (Individual Sound) === | |

| + | As we move to the [[Brahmana (ब्राह्मणम्)|Brahmana]], [[Aranyaka (आरण्यकम्)|Aranyaka]] and [[Upanishads (उपनिषदः)|Upanishad]] texts, we find a gradual unfolding of conceptual categories. A full spectrum of linguistic units is seen in the Samkhaayna Brahmana (26.5) where we find an important conversation between Jatukarnya and Aliikayu describing the constituents of speech units.<ref name=":5" /><blockquote>''Him he asked, ‘If the performer himself should note a flaw passed over or another should call attention to it, how is that flaw to be made flawless? By repetition of the Mantra or by an oblation?’ ‘The Mantra should be recited again,’ Jatukarnya said. Him Aliikayu again asked, ‘Should one recite in full the Shastra or recitation or Nigada or offering verse or whatever else it be?’ ‘So much as is erroneous only need be repeated, a verse (rcham), or half verse (ardharcam), or quarter verse (paadam), or word (padam), or individual sound (varnam),’ Jatukarnya replied.”''</blockquote>Not only do we find there a clear distinction between a paada “metrical foot” and pada “word”, we also find one of the early uses of the term varna to refer to “sound”, in contrast with the older term akshara “syllable”. Thus, there is clear conceptual and terminological progress from metrical feet to words, and from syllables to individual sounds. It is significant to note the emergence of the term "varna" used in the sense of sounds, a term which only refers to colors and social classes in the earlier literature. | ||

| − | + | === स्वर व्यञ्जनाश्च ॥ Svara and Vyanjana (Vowels and Consonants) === | |

| + | In the Aranyakas we see the further advances into pronunciation of samskrit sounds; the origin of the notion of svara, vyanjana and antastha (semi-vowel) among other pronunciations. Aitareya Aranyaka (3.2.6) reports many specific and detailed pronunciation and recitation aspects of Rigveda; it says the following about the emergence of vyanjanas<blockquote>तद्वा इदं बृहतीसहस्रं संपन्नं तस्य यानि व्यञ्जनानि तच्छरीरं यो घोषः स आत्मा य ऊष्माणः स प्राणः, इति । (Aita. Aran. 2.2.4)<ref>Aitareya Aranyaka ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%90%E0%A4%A4%E0%A4%B0%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%AF_%E0%A4%86%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%A3%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%8D/%E0%A4%86%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%A3%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%95_%E0%A5%A8 Aranyaka 2])</ref></blockquote>Thus, this [collection of] a thousand Brhati verses comes into existence. Of that collection, the vyanjanas (व्यञ्जनानि । consonants) are the shareera (body), the ghosha (घोषः । vowels) is its Atma, and the ushmana (ऊष्माणः । sibilants or aspiration sounds) its Prana (vital breath).<ref name=":5" /> | ||

| − | + | In the Chandogya Upanishad (2.22.5)<ref>Chandogya Upanishad ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%9B%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%A8%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D/%E0%A4%85%E0%A4%A7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%83_%E0%A5%A8 Adhyaya 2])</ref>, सर्वे स्वरा घोषवन्तो बलवन्तो वक्तव्या....। descriptions of the pronunciations evolved, such as that of svara, ghosha, sparsha etc. | |

| − | + | These two textual references strongly reflect on the beginnings of the shastra of pronunciation in ancient India. Some notable conclusions drawn from them are as follows | |

| − | + | * vowels are distinguished from consonants | |

| − | + | * among consonants a distinction between the stops (sparsha varnas) and aspiration sounds (ushamanas) is made. | |

| + | * notions of resonance (ghosha), openness of pronunciation (of aspirant sounds) and contact in pronunciation (of the sparsha "stop" varnas) have emerged. | ||

| + | * notion of semi-vowel (antastha) emerged in Aitareya Aranyaka (3.2.1). | ||

| + | The ancient Vedic schools developed major treatises analyzing sound, vowels and consonants, rules of combination and pronunciation to assist clear understanding, to avoid mistakes and for resonance (pleasing to the listener). These texts include Samhita-pathas and Pada-pathas of the vedas.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

| − | === | + | === Akshara Samaamnaaya === |

| − | + | Over time a process of linguistic standardization of the orally received vedic literature developed and a standardized samskrit alphabet came into existence, having a specific name: Akshara samaamnaaya. This is a very important term, was continued to be used in the later formal works like Mahabhaashya, which is Maharshi Patanjali’s “Great Commentary” on the famous samskrit grammar of Maharshi Panini. The term akshara-samamnaya is important because it shows a connection with the past. The term akshara, which refers to syllables, has been used here to refer to individual sounds. As discussed earlier extension of terms has a significant impact on the terminology and meaning of words in linguistic sense.<ref name=":5" /> | |

| + | # akshara which referred to "syllables" now refers to "individual sounds" also | ||

| + | # pada from a "metrical foot" came to mean a "word" | ||

| + | # varna extended from color and social group to mean a "sound" | ||

| + | # samaamnaaya is used to refer to a "cumulative recitation" an oral catalogue of sounds, an ordered form of alphabet. | ||

| + | This period saw a loss of ancient accents and of the ability to pronounce samskrit sounds creating a gap between the orally preserved ancient texts and the current form of samskrit as well as vernacular languages. The importance of learning grammar and pronunciation was stressed on quoting the story of Vrtrasura. The Aitareya Aranyaka (3.1.5; 3.2.6) shows debates concerning sandhis in Vedic texts and whether the Vedic texts should be pronounced with or without the retroflexes श and ण. The process of standardization was meant to put an end to such doubts. The development of the technical apparatus of samkrit pronunciation seems to have come about to put an effective end to many differences and doubts. However, in the later degenerate times, the grammarians claimed, the priests stopped studying grammar and phonetics before studying the Vedas, and this led to a deplorable state of Vedic recitation. | ||

| − | + | === Formal Pronunciation Texts === | |

| − | + | In the next phase, recognizing the need for an organized process of standardization, formal treatises called '''Pratisakhyas''' came into existence. The Pratisakhyas, as indicated by the etymology of the name from prati “each” + shaka “branch”, are texts where each of them relates to a particular Vedic shaka and is primarily concerned with describing the pronunciation and euphonic peculiarities of a particular Vedic text. There is also a clear linkage between the Pratisakhya tradition and the authorities mentioned in vedic texts such as the Aitareya Aranyaka. Besides this, some of the important texts in this category are the Taittiriya, Vajasaneyi pratisakhyas, the Rktantra, and the Saunakiya chaturaadhyayika.<ref name=":5" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Another class of pronunciation treatises is referred to by the general term '''Śikṣā''' (referred to as '''Shiksha''') meaning training in general, and pronunciation and recitational training in particular. The word Śikṣā appears in the Taittriya Upanishad involving detailed explanation of the training in pronunciation aspects. As a class of texts, over a hundred these Śikṣā texts have been produced by different authorities which are relatively modern to the Pratisakhyas. The most well known among these texts is the Paniniya Shiksa attributed by the tradition to the famous Sanskrit grammarian Panini. Other important Shikshas include the Vyasa, Apisali, Yajnavalkya, and the Narada shiksha. A few of these texts, such as the Paniniya shiksha and the Apisali siksha, are non-sectarian in the sense that they do not attach themselves to a particular Vedic school, and deal with the Sanskrit language in a generic way. However, most of these texts are sectarian. They are attached to particular Vedic schools, and deal with the recitation of particular Vedic texts. They often provide the most minute details of the recitational practice.<ref name=":5" /> | |

| − | + | ==वर्णोत्पत्तिः ॥ Varnotpatti== | |

| − | | | + | Varnas are the fundamental speech units and they are produced (वर्णोत्पत्तिः) by a complex process involving the antaranga or inner mind combined with air and articulating organs. Panini shiksha and other texts describe the physiological process by which [[Origin and Propagation of Sound (शब्दोत्पत्तिः प्रसारश्च)|sound (or varnas here) is produced]] in the human being. According to Paniniya Shiksha, <blockquote>वर्णाञ्जनयते तेषां विभागः पञ्चधा स्मृतः॥9॥ स्वरतः कालतः स्थानात्प्रयत्नानुप्रदानतः। इति वर्णविदः प्राहुर्निपुणं तन्निबोधत ॥10 (Pani. Shik<ref name=":0">Paniniya Shiksha ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%B0%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%97%E0%A4%83:%E0%A4%B6%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%BE Full Text])</ref>) </blockquote>Varnas or Speech sounds are generated in five following ways<ref name=":1" /> |

| − | + | # स्वरः ॥ Svara (Accent or Pitch) are three in number: udātta, anudātta, and Svarita. | |

| − | |- | + | # मात्रा ॥ Matra (Quantity or time of utterance) are three in number: ह्रस्व (hrasva = short), दीर्घ (dīrgha = long) and प्लुत (pluta = longer) |

| − | + | # स्थानम् ॥ Sthana (Place of articulation) are eight in number: | |

| − | |- | + | # प्रयत्नः ॥ Prayatna (Effort): |

| − | + | # अनुप्रदानम् ॥ Anupradana (Sound material) | |

| − | | | + | |

| − | + | === वर्णाः ॥ Varnas or Sounds === | |

| − | |- | + | The Vedas contain 52 characters (sounds) (13+27+8+4) as follows.<ref name=":6" /> |

| − | + | ||

| − | | | + | * Svaras or Vowels - 13 |

| + | * Sparsha or Consonants (from क to म and ल् and ल्ह्) 27 | ||

| + | * य र ल व श ष स ह - 8 | ||

| + | * Visarga, Anusvara, Jivhamuliya and Upadhmaniya (half Visarga signs before क and प) 4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Paniniya Shiksha, varnas in Samskrit are assumed to be 63 (21+25+8+4+5) in number as follows (assuming संवृत and विवृत अ to be separate they are 64 in number).<ref name=":6" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Svaras or Vowels (including hrasva, deergha and plutha etc) they are 21 in number. | ||

| + | * Consonants (from क to म) are 25 in number. | ||

| + | * य र ल व श ष स ह are 8 in number. | ||

| + | * Dual forms of य र ल व are 4 in number | ||

| + | * Visarga, Anusvara, Jivhamuliya, Upadhmaniya and Plutha लृ are 5 in number. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === स्वरः ॥ Accent or Pitch === | ||

| + | Svaras are of three types - Udaatta, Anudatta, Svarita. As seen above the Svaras or Vowels are fundamental syllables while here the Svara refers to accent or pitch. While difference in accent causes a difference in meaning in the vedic literature, accent is not given importance in classical samskrit literature. The अचः (acaḥ = vowels) are called स्वराः (svarāḥ) as they shine with 'svara' and being the 'dharma', udātta etc. are also called svarāḥ. Panini in his famous Ashtadhyayi defines svaras as follows<ref name=":1">Vedangas - Siksha by Prof. Korada Subrahmanyam</ref><blockquote>उच्चैरुदात्तः ॥ uccairudāttaḥ ॥ १-२-२९ ॥ If the vowel is pronounced in the upper parts, it is called udātta.</blockquote><blockquote>नीचैरनुदात्तः ॥ nīcairanudāttaḥ ॥ १-२-३0 ॥ If the vowel is pronounced in the lower parts, it is called anudātta.</blockquote><blockquote>समाहारः स्वरितः ॥ samāhāraḥ svaritaḥ ॥ १-२-३१ ॥ Svarita is the combination of udātta and anudātta. (Asht. 1.2.29-31)<ref name=":2">Maharshi Panini's Ashtadhyayi ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%85%E0%A4%B7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%9F%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%A7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%80_%E0%A5%A7#%E0%A4%AD%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%97_%E0%A5%A7.%E0%A5%A8 Adhyaya 1 Pada 2])</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === मात्रा ॥ Matra === | ||

| + | Following the time taken for pronunciation, the vowels (acaḥ = vowels) are named ह्रस्व (hrasva = short), दीर्घ (dīrgha = long) and प्लुत (pluta = longer). The time for these vowels is fixed by Yajnavalkya in his Shiksha<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>एकमात्रो भवेद्ध्रस्वः द्विमात्रो दीर्घ उच्यते। त्रिमात्रस्तु प्लुतो ज्ञेयः व्यञ्जनं त्वर्धमात्रकम् ॥ १३ ॥ (Yajn. Shik. 13)</blockquote><blockquote>ekamātro bhaveddhrasvaḥ dvimātro dīrgha ucyate । trimātrastu pluto jñeyaḥ vyañjanaṃ tvardhamātrikam ॥ 13 ॥</blockquote>If the vowel is uttered in a single mātrā or the time taken for the fall of an eyelid, then it is called hrasva, if it is two mātras, then it is dīrgha and if takes three mātras, then it is pluta. A hal (consonant) has got half-a-mātrā time. 'a' (अ) is hrasva; ā (आ) is dīrgha; and 'a3' (अ३) is pluta. For hal, 'क् क्' (k k) takes one mātrā and for a single consonant, it is half-a-mātrā. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Panini in his Ashtadhyayi gives a natural example to imitate the pronunciation of hrasva, dīrgha and pluta – <blockquote>ऊकालोऽच् ह्रस्वदीर्घप्लुतः ॥ १-२-२७ ॥ ūkālo'c hrasvadīrghaplutaḥ ॥ 1-2-27 ॥ (Asht. 1.2.27)<ref name=":2" /> </blockquote>A cock's sound has to be taken as an example of hrasva, dīrgha and pluta, i.e. the time taken by a cock to pronounce u, o and o3 (उ, ओ, ओ३) is the right time to follow. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Gandharvaveda (the Veda of Music), which is an [[Upavedas (उपवेदाः)|Upaveda]], there are seven svaras - ṣaḍja (sa), ṛṣabha (ri), gāndhāra (ga), madhyama (ma), pañcama (pa), dhaivata (da) and niṣāda (ni) – "sa-ri-ga-ma-pa-da-ni". They are born out of udatta, anudatta and svarita – explains Panini in his Shiksha: <blockquote>उदात्ते निषादगान्धरौ अनुदात्त ऋषभधैवतौ। स्वरितप्रभवा ह्येते षड्जमध्यमपञ्चमाः ॥ १२ ॥ (Pani. Shik. 12)<ref name=":0" /></blockquote><blockquote>udātte niṣādagāndharau anudātta ṛṣabhadhaivatau । svaritaprabhavā hyete ṣaḍjamadhyamapañcamāḥ ॥ 12 ॥</blockquote>Both niṣāda and gāndharva are born from udātta, ṛṣabha and dhaivata from anudātta, and ṣaḍja, madhyama and pañcama are from svarita. | ||

| + | |||

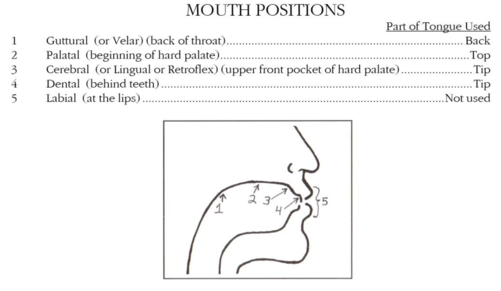

| + | === स्थानम् ॥ Sthana === | ||

| + | [[File:Positions in Mouth - Pronunciation.PNG|thumb|501x501px|Location of articulation of varnas in the mouth organ according to Panini]] | ||

| + | Sthanas are the places (or body parts which play a role in the production of sound) of articulation of varnas. Paniniya Shiksa defines eight places of articulation.<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>अष्टौ स्थानानि वर्णानामुरः कण्ठः शिरस्तथा। जिह्वामूलं च दन्ताश्च नासिकोष्ठौ च तालु च॥ १३ ॥ (Pani. Shik. 13)<ref name=":0" /></blockquote><blockquote>aṣṭau sthānāni varṇānāmuraḥ kaṇṭhaḥ śirastathā । jihvāmūlaṃ ca dantāśca nāsikoṣṭhau ca tālu ca ॥ 13 ॥ </blockquote>There are eight places where letters are produced – chest, throat (pharynx), roof of palate, the root of the tongue, teeth, nose, both the lips and palate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Places of Articulation of Samskrit Varnas ==== | ||

| + | In the following table, the short and long vowels are represented by the short vowel; i.e. अ (a) stands for आ (ā) as well, and similarly in the case of other vowels wherever applicable. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="background: #ffad66;" - | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | !Letters | ||

| + | !Place of Articulation | ||

| + | !English Equivalent | ||

| + | !Panini Sutra | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |अ, क, ख, ग, घ, ङ, ह, ः | ||

| + | |||

| + | a, ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa, ha, ḥ | ||

| + | |कण्ठः (throat) | ||

| + | |||

| + | kaṇṭhaḥ | ||

| + | |Guttural/Velar | ||

| + | |अकुहविसर्जनीयानां कण्ठः। | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |इ, च, छ, ज, झ, ञ, य, श | ||

| + | |||

| + | i, ca, cha, ja, jha, ña, ya, śa | ||

| + | |तालु (palate) | ||

| + | |||

| + | tālu | ||

| + | |Palatal | ||

| + | |इचुयशानां तालु। | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |ऋ, ट, ठ, ड, ढ, ण, र, ष | ||

| + | |||

| + | ṛ, ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, ra, ṣa | ||

| + | |मूर्धा (roof of palate) | ||

| + | |||

| + | mūrdhā | ||

| + | |Cerebral/Lingual/Retroflex | ||

| + | |ऋटुरषाणां मूर्धा। | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |ऌ, त, थ, द, ध, न, ल, स | ||

| − | + | ḷ, ta, tha, da, dha, na, la, sa | |

| + | |दन्ताः (teeth) | ||

| − | + | dantāḥ | |

| + | |Dental | ||

| + | |ऌतुलसानां दन्ताः। | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |उ, प, फ, ब, भ, म, [[File:Jihvamula Pa.png|thumb|17x17px|ḫ]]u, pa, pha, ba, bha, ma | ||

| + | |ओष्ठौ (lips) | ||

| − | = | + | oṣṭhau |

| − | + | |Labial | |

| − | + | |उपूपध्मानीयानामोष्ठौ। | |

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |ञ, म, ङ, ण, न | ||

| − | + | ña, ma, ṅa, ṇa, na | |

| + | |नासिका च (also nose) | ||

| − | + | nāsikā ca | |

| − | + | |Nasal | |

| − | + | |ञमङणनानां नासिका च। | |

| − | + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | |

| − | + | |7 | |

| + | |ए , ऐ | ||

| − | + | e, ai | |

| + | |कण्ठतालु (throat and palate) | ||

| − | + | kaṇṭhatālu | |

| + | |Gutturo-palatal | ||

| + | |एदैतोः कण्ठतालु। | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |8 | ||

| + | |ओ, औ | ||

| − | + | o, au | |

| − | + | |कण्ठोष्ठम् (throat and lips) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | kaṇṭhoṣṭham | |

| − | + | |Gutturo-dental | |

| − | + | |ओदौतोः कण्ठोष्ठम्। | |

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | |9 | ||

| + | |व | ||

| − | + | Va | |

| − | + | |दन्तोष्ठम् (teeth and lips) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | dantoṣṭham | |

| − | + | |Labio-dental | |

| − | + | |वकारस्य दन्तोष्ठम्। | |

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |10 | ||

| + | |क | ||

| − | + | h | |

| − | + | |जिह्वामूलम् (root of the tongue) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | jihvāmūlam |

| − | + | | | |

| + | | | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | |11 | ||

| + | |ं (अनुस्वार) | ||

| − | + | ṃ | |

| − | + | |नासिका (nose) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | nāsikā | |

| − | + | |Nasal | |

| − | : '' | + | | |

| − | + | |} | |

| + | <blockquote>हकारं पञ्चमैर्युक्तम् अन्तस्थाभिश्च संयुतम् । औरस्यं तं विजानीयात् कण्ठ्यमाहुरसंयुतम् ॥ पाणिनीयशिक्षा, १६ ॥</blockquote><blockquote>hakāraṃ pañcamairyuktam antasthābhiśca saṃyutam । aurasyaṃ taṃ vijānīyāt kaṇṭhyamāhurasaṃyutam ॥ (Pani. Shik. 16)<ref name=":0" /></blockquote>The combinations of ह-'ha' and ङ-ṅa / ञ-ña / ण-ṇa / न-na / म-ma / य-ya / र-ra / ल-la / व-va, i.e. ह्ङ-hṅa, ह्ञ-hña, ह्ण-hṇa, ह्न-hna, ह्म-hma, ह्य-hya, ह्र-hra, ह्ल-hla and ह्व-hva, are to be pronounced from the chest. The lone 'ह-ha' is born in the throat. The combination of ha + ṅa and ha + ña (ह्ङ-hṅa and ह्ञ-hña) is not present in word usages. In words like aparāhṇa (अपराह्णः), madhyāhna (मद्याह्नः), brahma (ब्रह्मा), bāhya (बाह्या), hrada (ह्रद), prahlāda (प्रह्लादः) and āhvāna (आह्वानम्), 'ha' is to be pronounced carefully, i.e. it should come from the chest. | ||

| − | + | ==== Varnas in Samskrit Language ==== | |

| − | : | + | According to Yajnavalkya Shiksha varnas are classified into four. |

| − | : '' | + | <div style="column-count:2;-moz-column-count:2;-webkit-column-count:2"> |

| − | + | # स्वराः (Svaras) (9 Vowels) | |

| − | + | # स्पर्शाः (Sparsha) (25) | |

| + | # अन्तस्थाः (Antastha) (4) | ||

| + | # ऊष्माणः (Ushmana) (4) | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |+Samskrit Varnas (9 Vowels and 33 Consonants) | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | !Varnas | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" ! | ||

| + | ! rowspan="2" |अचः (acaḥ = vowels) | ||

| + | |अ आ इ ई उ ऊ ऋ ॠ ऌ ए ऐ ओ औ अं अः | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |a ā i ī u ū ṛ ṝ ḷ e ai o au aṃ aḥ | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | ! rowspan="2" |हल् (consonants) | ||

| + | |क ख ग घ ङ च छ ज झ ञ ट ठ ड ढ ण त थ द ध न प फ ब भ म | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |ka kha ga gha ṅa ca cha ja jha ña ṭa ṭha ḍa ḍha ṇa ta tha da dha na pa pha ba bha ma | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f0f8ff;" | ||

| + | ! rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | |य र ल व श ष स ह | ||

| + | |- style="background: #f5f5f5;" | ||

| + | |ya ra la va śa ṣa sa ha | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | As explained in the previous section syllables (not letters) were called Akshara, meaning 'imperishable'. The aksharas or varnas are classified mainly into two types:<ref>Siddhanta Kaumudi by Bhattoji Diksita and Laghu Siddhanta Kaumudi by Varadaraja.</ref> | ||

| + | * '''Svara''' (अचः) or Vowels which are 9 in number | ||

| + | * '''Vyanjana''' (हल्) or Consonants which are 33 in number | ||

| − | + | ''Svara aksharas'' are also known as ''prana akshara''; i.e., they are the main sounds in speech, without which speech is not possible. The term Svara here refers to the Varna and is not to be confused with accent or pitch which is also called Svara. ''Vyanjana'', i.e., consonants are incomplete and associate with vowels for pronunciation. They are also known as ''Prani akshara''; that is, they are like a body to which life (''svara'') is added. They include the rest of the three types apart from Svaras varnas namely '''Sparsa''' (mentioned as Stop), '''Antastha''' and '''Ushmana'''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Sparsa aksharas include syllables from ''ka'' to ''ma''; they are 25 in number. Antastha aksharas include syllables ''ya'', ''ra'', ''la'' and ''va''. Usman aksharas include ''śa'', ''ṣa'', ''sa'' and ''ha''. | |

| − | |||

| − | {| class="wikitable" |+ | + | A vowel is pronounced in 18 ways (3×2×3), based on matra (time), its organ, and svara (accent) of pronunciation. However, there are some modifications. We get 18 ways of pronunciation for अ इ उ ऋ, ऌ has no Dirgha (2x2x3 = 12 ways), ए ओ ऐ औ has no Hrasva, so we get (2x2x3) twelve ways. |

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |+Factors involved in Vowel Pronunciation | ||

| + | !Matra (मात्रा ) | ||

| + | unit of time is a ''mātra'' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * '''Hrasva''': Short vowel, Eka-mātra | ||

| + | * '''Dīrgha''': Long vowel, Dvi-mātra | ||

| + | * '''Plutha''': Prolonged vowel, Tri-mātra | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | !Organ involved in pronunciation |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | * '''Mukha''': Oral (open) | |

| − | + | * '''Nāsika''': Nasal | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! ''[[ | + | !Svaras (Accent or Pitch) |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | * '''Udātta''': high pitch | |

| − | + | * '''Anudātta''': low pitch | |

| − | | | + | * '''Svarita''': descending pitch |

| − | | | + | |} |

| − | | | + | |

| + | ==== वृत्तिः॥Vṛtti ==== | ||

| + | Nāradīyaśikṣā prescribes three vṛttis (procedures) called druta (द्रुता । quick), madhyama (मध्यमा । medium) and vilambita (विलम्बितम् । slow) that are useful in articulation of speech: <blockquote>अभ्यासार्थं द्रुतां वृत्तिं प्रयोगार्थे तु मध्यमाम् । शिष्याणामुपदेशार्थे कुर्याद्वृत्तिं विलम्बितम् ॥ २१ ॥ (Nara. Shik. 21)</blockquote><blockquote>abhyāsārthaṃ drutāṃ vṛttiṃ prayogārthe tu madhyamām । śiṣyāṇāmupadeśārthe kuryādvṛttiṃ vilambitam ॥ 21 ॥</blockquote>For practicing or recitation Drutavṛtti, for conversation Madhyama, and for teaching students vilambita vrtti are to be employed. In drutavṛtti, nine drops flow out of suṣumnā nāḍī, in madhyamā, twelve drops and in vilambita, sixteen drops are said to flow out of suṣumnā nāḍī. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === प्रयत्नः ॥ Prayatna (Effort) === | ||

| + | Effort (or Prayatna) of articulation is of two types for consonants, | ||

| + | # '''Bāhya Prayatna''': External effort | ||

| + | # '''Abhyantara Prayatna''': Internal effort | ||

| + | ## '''Alpaprāna''': Unaspirated | ||

| + | ## '''Mahāprāna''': Aspirated | ||

| + | ## '''Śvāsa''': Unvoiced | ||

| + | ## '''Nāda''': Voiced | ||

| + | |||

| + | == स्वरतो वर्णतो वा अपराधम् ॥ Effects of Bad Pronunciation == | ||

| + | Pāṇini provides a natural example for perfect pronunciation:<blockquote>व्याघ्री यथा हरेत् पुत्रान् दंष्ट्राभ्यां न तु पीडयेत् । भीता पतनभेदाभ्यां तद्वद्वर्णान् प्रयोजयेत् ॥ २५ ॥</blockquote><blockquote>vyāghrī yathā haret putrān daṃṣṭrābhyāṃ na tu pīḍayet । bhītā patanabhedābhyāṃ tadvadvarṇān prayojayet ॥ 25 ॥</blockquote>Summary: Just as a tigress carries its cubs carefully in her sharp jaws without causing any pain to them, afraid about their falling down or being cut accidentally, similarly one should pronounce letters like that (using the same precautions). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pāṇinī further cautions against any mispronunciation in terms of accent or letter and asserts that such a usage would bring about disastrous consequences to the yajamana:<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>मन्त्रो हीनः स्वरतो वर्णतो वा मिथ्याप्रयुक्तो न तमर्थमाह । स वाग्वज्रो यजमानं हिनस्ति यथेन्द्रशत्रुः स्वरतोऽपराधात् ॥ ५२ ॥</blockquote><blockquote>mantro hīnaḥ svarato varṇato vā mithyāprayukto na tamarthamāha । sa vāgvajro yajamānaṃ hinasti yathendraśatruḥ svarato'parādhāt ॥ 52 ॥</blockquote>A mantra that is defective in terms of accent or letter would not be useful as it does not convey the intended meaning. Moreover it will become a weapon as good as the diamond-weapon of Indra, and boomerangs against the doer. This is what happened when the mantra 'indraśatruḥ vardhasva' was employed with a different accent. The following story from Taittirīyasaṃhitā (2.5.2.1), and Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 1.5.2.10 (Shuklayajurveda) is being referred to by the quoted mantra – <blockquote>अथ यदब्रवीत् – इन्द्रशत्रुर्वर्धस्वेति तस्मादु हैनमिन्द्र एव जघान। अथ यद्ध शश्वदवक्ष्यत् – इन्द्रस्य शत्रुर्वर्धस्वेति शश्वदुह स इन्द्रमेवाहनिष्यत् ।</blockquote><blockquote>atha yadabravīt – indraśatrurvardhasveti tasmādu hainamindra eva jaghāna. atha yaddha śaśvadavakṣyat – indrasya śatrurvardhasveti śaśvaduha sa indramevāhaniṣyat</blockquote>Visvarūpa was the son of Tvaṣṭā. The former was killed by Indra. Tvaṣṭā wanted to avenge and commenced a sacrifice called 'abhicārahoma' in order to have a son who can kill [[Indra (इन्द्रः)|Indra]]. Then, while praying to Fire-God (āhavanīyāgni) a mantra, i.e. 'svāhendraśatrurvardhasva', which means – "O! Fire-God! Prosper as a person who can kill Indra" was guessed. In the mantra 'śatru' means destroyer and in such a case it should be employed with 'antodāttasvara' as it is a Tatpuruṣasamāsa, i.e. indrasya śatruḥ. But the priest employed the same mantra as 'ādyudātta', which is a Bahuvrīhisamāsa, which means 'be born as one, who has got Indra as the destroyer'. As a result Indra became the destroyer of [[Vrtrasura (वृत्रासुरः)|Vṛtra]], who was killed soon after his birth. Therefore, in order to avoid such repercussions, one should be careful in his speech actions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == वेदपाठकगुणाः ॥ Qualities of a Vedapathaka == | ||

| + | In the recitation of vedamantras, just as svara or varna doshas leading to disastrous consequences are described these granthas also explain the beneficial effects. In all shikshas it has been emphasized that proper, accurate, accented pronunciation of the veda mantras must be adhered to obtain the desired results. Vyasa shiksha describes four basic qualities of a Vedapathaka<ref name=":4">P. N. Pattabhirama Sastri. (1976) ''Vyasa Siksha, With Vedataijas Commentary of Sri. Suryanarain Suravadhani and Sarva Lakshanmanjari Sangraha of Sri. Raja Ganapati.'' Varanasi: Veda Mimamsa Research Center (Page 39-45)</ref><blockquote>सुव्यक्तस्सुस्वरो धैर्यं तच्चित्तत्वं चतुर्गुणाः । एतद्युक्तः पठेद्वेदं स वेदफलमश्नुते ॥ (Vyas. Shik. 503)</blockquote>Four basic requisites for obtaining the desired results of recitation of vedamantras are enumerated: सुव्यक्तम् (suvyaktam) i.e., recitation according to rules of ucchaarana, सुस्वरः (susvara) i.e., pronouncing according to the rules of svara in a nasal free voice, धैर्यं (dhairyam) i.e., giving undivided attention pronouncing with confidence (avoiding shaky voice), तच्चित्तत्वं (tacchitatvam) i.e., (student) being completely absorbed in the vedic recitation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acharyas are cautioned to watch for the above mentioned four qualities in students both in adequate proportion amount and combination. The Acharya himself must have the ability to distinguish the svara and varna doshas, thus should have exceptional hearing abilities to weed out the errors and correct them in a student. Probably because of this requirement the study is referred to as tapasya, always requiring the concentration of mind and well concerted assiduous efforts in listening as well as in erudition.<blockquote>ध्वनिस्स्थानञ्च करणं प्रयत्नः कालता स्वरः। देवताजातिरेतैश्च वर्णा ज्ञेया विचक्षणैः ॥</blockquote><blockquote>पदक्रमविशेषज्ञो वर्णक्रमविचक्षणः । स्वरमात्राविभाज्ञो गच्छेदाचार्यसम्पदम् ॥ (Vyas. Shik. 511-512)<ref name=":4" /></blockquote>One who understands and discerns the dhvani (sound) sthanas (place of articulation), karanas (articulators), prayatnas (efforts), kalata (notion of time), devatas associated with varnas, the grouping (jati), is an expert in padakrama and varnakrama and knows the svaras and matras - such a person attains the position of Acharya. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Paniniya Shiksha mentions the following six qualities required of a Vedapathaka.<ref name=":6" /><blockquote>माधुर्यमक्षरव्यक्तिः पदच्छेदस्तु सुस्वरः । धैर्यं लयसमर्थं च षडेते पाठका गुणाः ।। (Pani. Shik. 33)</blockquote>They are: | ||

| + | |||

| + | # माधुर्यम् - to speak sweetly | ||

| + | # अक्षरव्यक्तिः - Clear pronunciation of letters. | ||

| + | # पदच्छेदः - Speaking with appropriate word breaks. | ||

| + | # सुस्वरः - To speak with optimal sound. | ||

| + | # धैर्यं - Speaking calmly. | ||

| + | # लयसमर्थं - Speaking rhythmically (not noise). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Paniniya Shiksha also mentions the following six doshas or negative qualities to be avoided by a Vedapathaka.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | गीती शीघ्री शिरःकम्पी तथा लिखितपाठकः । | ||

| + | |||

| + | अनर्थज्ञोऽल्पकण्ठश्च षडेते पाठकाधमाः ।। (Pani. Shik. 32) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pathaka-adhamas are those who recite with the following six doshas: | ||

| + | |||

| + | # गीती - to recite in a singing manner | ||

| + | # शीघ्री - to recite in a fast manner | ||

| + | # शिरःकम्पी - shaking the head while reciting | ||

| + | # लिखितपाठकः - read written instead of chant | ||

| + | # अनर्थज्ञः - recite without the knowledge of the meaning | ||

| + | # अल्पकण्ठः - recite an incompletely memorized mantra in a low voice | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==प्रातिशाख्यानां शिक्षास्वरूपता ॥ Pratishakhyas related to Shiksha== | ||

| + | Pratisakhyas are the oldest Siksa textbooks intimately connected to shakas of [[The Four Vedas (चतुर्वेदाः)|the four Vedas]]. Although specific in subject matter their contribution in protecting the vedic form, is as invaluable as that of Vyakarana and Siksha texts. Their textual content differs from Vyakarana and Shiksha granthas in that they deal exclusively with the peculiarities of that particular veda shaka in the areas of svaras, sandhis and other pronunciation aspects and are thus as old as the Vedas themselves.<ref name=":3" /> Later Siksa texts are systematic, and often titled with suffix "Siksa", such as the Naradiya-Siksa, Vyasa-Siksa, Paniniya-Siksa and Sarvasammata-Siksa. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Pratishakhyas, which evolved from the more ancient Vedic padapathas, deal with the manner in which the Vedas are to be enunciated. There are separate Pratishakhyas for each Veda and they are composed either in sutra or shloka formats. They complement the books called Shiksha written by various authorities. Several Pratishakhyas have survived into the modern era:<ref name=":122">Pt. Baldev Upadhyaya (1997) ''Samskrit Vangmay ka Brhad Itihas, Dvitiya Khand - Vedang.'' Lucknow: Uttar Pradesh Samskrit Sansthan (Pages 1-55)</ref> | ||

| + | * Rigveda-Pratishakya: Composed by Shaunaka | ||

| + | * Vajasaneya-Pratishakhya: Composed by Katyayana | ||

| + | * Taittiriya (Krishna Yajurveda) Pratishakhya | ||

| + | * Samaveda-Pratishakhyas: Four of them are - Rig-tantra, Samatantra, Akshara-tantra, Pushpa sutras | ||

| + | * Atharvaveda-Pratishakhya (Shaunakiya shakha) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Shiksha Texts and the Pratishakhyas led to great clarity in understanding the surface structure of language. For clarity of pronunciation, they broke up the large Vedic compounded structures into word stems, prefixes, and suffixes. Certain styles of recitation, such as the vikriti pathas'','' involved switching syllables, repeating the last word of a line at the beginning of the next, and other permutations. In the process, a considerable amount of morphology is discussed, particularly regarding the combination of sequential sounds, which leads to the modalities of sandhi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Shiksha Granthas== | ||

| + | There are 35 Shiksha granthas available. These contain detailed descriptions of the pronunciation of mantras etc. A collection of 32 texts has been published named 'Shiksha-Sangraha'. Many important facts related to phonetics, difference between vowels and consonants, various differences related to uttering of vowels, description of place and effort etc. in pronunciation of varnas, difference between Anusvara and Anunasika, different forms of Visarga, scientific process of pronunciation of varnas, relation of Udatta svaras with the notes of the sargam, existence of hrasva ए and ओ, samvrit (closed form) and vivrita (open forms) of ओ and औ, rules regarding pronunciation, analysis of sandhi etc.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Shiksha texts exist, most of them in metrical verse form but a few in sutra form. The following list contains some of these surviving texts:<ref name=":122" /> {{columns-list|colwidth=10em|style=width: 600px;|# Amoghanandini | ||

| + | # Apisali (in sutra form) | ||

| + | # Aranya | ||

| + | # Atreya | ||

| + | # Avasananirnyaya | ||

| + | # Bharadvaja | ||

| + | # Chandra | ||

| + | # Charayaniya | ||

| + | # Galadrka | ||

| + | # Kalanirnya | ||

| + | # Katyayani | ||

| + | # Kaundinya | ||

| + | # Keshavi | ||

| + | # Keshavi (Shloka form) | ||

| + | # Kramakarika | ||

| + | # Kramasandhaana | ||

| + | # Laghumoghanandini | ||

| + | # Lakshmikanta | ||

| + | # Lomashi | ||

| + | # Madhyandina | ||

| + | # Mandavya | ||

| + | # Mallasharmakrta | ||

| + | # Manasvaara | ||

| + | # Manduki | ||

| + | # Naradiya | ||

| + | # Paniniya (Sutra form) | ||

| + | # Paniniya (Shloka form) | ||

| + | # Paniniya (With Accents) | ||

| + | # Parashari | ||

| + | # Pari | ||

| + | # Pratishakhyapradipa | ||

| + | # Sarvasammata | ||

| + | # शैशिरीय (Shaishiriya) | ||

| + | # Shamaana | ||

| + | # Shambhu | ||

| + | # षोडशश्लोकी (Shodashashloki) | ||

| + | # Shikshasamgraha | ||

| + | # Siddhanta | ||

| + | # श्वराङ्कुशा (Svaraankusha) | ||

| + | # Svarashtaka | ||

| + | # Svaravyanjana | ||

| + | # Vasishtha | ||

| + | # Varnaratnapradipa | ||

| + | # Vyaali | ||

| + | # Vyasa | ||

| + | # Yajnavalkya }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although many of these Shiksha texts are attached to specific Vedic schools, others are later day texts. The following table gives a summary of them.<ref>https://egyankosh.ac.in/handle/123456789/93868</ref> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" |Veda | ||

| + | |Associated Shiksha granthas | ||

| + | |Number | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! colspan="2" |Rigveda |

| − | + | |स्वराङ्कुश। Svarankusha, षोडशश्लोकी । Shodasha shloki, शैशिरीय । Shaishireeya, आपिशलि । Aapishali, पाणिनीय। Paniniya | |

| − | + | |5 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! rowspan="2" |Yajurveda |

| − | | | + | |Shukla |

| − | | | + | |याज्ञवल्क्य। Yajnavalkya,वासिष्ठी। Vasishthi, कात्यायनी। Katyayani, पाराशरी। Parashari, माण्डव्य ।Mandavya, अमोघनन्दिनी । Amoghanandini, लघु अमोघनन्दिनी । Laghu Amoghanandini, माध्यन्दिनी । Mandhyandini, वर्णरत्न प्रदीपिका ।Varnaratna pradipika, केशवी । Keshavi, हस्तस्वरप्रक्रिया ।Hastasvara prakriya, अवसाननिर्णय । Avasana-nirnaya, स्वरभक्तिलक्षणपरिशिष्ट ।Svarabhakti-lakshana-parishishta, क्रमसन्धान । krama-sadhana, मनःस्वार । Manasvaara, यजुर्विधान । Yajurvidhana, स्वराष्टक। Svarashtaka, क्रमकारिका । Kramakarika |

| − | + | |18 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | |Krishna | |

| − | + | |भारद्वाज । Bharadvaja, व्यास । Vyasa, शम्भु। Shambhu, कौहलीय ।Kauhaliya, सर्वसम्मत। Sarvasammata, आरण्य। Aaranya, सिद्धान्त । Siddhanta | |

| − | + | |7 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! colspan="2" |Samaveda |

| − | + | |गौतमी । Gautami, लोमशी । Lomashi, नारदीय। Naradiya | |

| − | + | |3 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! colspan="2" |Atharvaveda |

| − | + | |माण्डूकी । Manduki | |

| − | + | |1 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Vedangas]] | [[Category:Vedangas]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 22:22, 14 April 2024

Shiksha (Samskrit: शिक्षा) is a shastra pertaining to pronunciation and accent which has a major role in the preservation of the vaidika mantras; as such it is insufficiently expressed as phonetics.[1] In this context it refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies, the others being Vyākaraṇam (Grammar), Chandas (Prosody), Niruktam (Semantics and Thesaurus), Jyotiṣam (Astrology) and Kalpa (Practice of Rites). It has an important place in the Vidyasthanas and hence study of this shastra is a prerequisite for Vyakarana.

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

Shiksha is considered as the nose (घ्राणम् - ghrāṇam) of Vedapuruṣa (knowledge personified) as described in Mundakopanishad (1.1.15). Unlike other later day languages, pronunciation is of utmost importance in Samskrit. Different speech organs, places for different letters, the efforts, the accents, quantity, pitch, stress, melody, process of how letters are produced, the virtues and vices of pronunciation, the problem with mispronunciation etc. are discussed in this science of pronunciation dealt with, in the Shad Vedangas. The literature pertaining to Vedanga Shiksa is classified into Pratishakhyas and Shiksagranthas.

Each ancient vaidika parampara survived through millenia as they developed pronunciation and the testimony to this is fact, are the surviving texts, namely Pratishakyas. It is the effect of this knowledge that the utterance of vaidika mantras have been unchanged in each parampara. The Paniniya-Shiksha and Naradiya-Shiksha are examples of extant ancient manuscripts of this field of Vedic studies.

Phonetics (in Modern Linguistics) is a rough translation of Śikṣā. The latter deals with many issues related to pronunciation unlike the former word where only a few linguistic aspects are discussed. The term Śikṣā literally means – the one that trains pronunciation etc. of letters.

व्युत्पत्तिः ॥ Etymology

The word Shiksha (शिक्षा । Śikṣā) has been derived from the dhatu शक् in the meaning, 'शक्तौ to be able' - शक्तुं शक्तो भवितुमिच्छा शिक्षा is the vyutpatti that applies here according to Pt. Ramprasad Tripathi.[2]

The roots of Shiksha can be traced to Rigveda which dedicates two hymns 10.125 and 10.71 to revere sound as a deity, and links the development of thought to the development of speech. Taittiriya Upanishad, in Shikshavalli, contains one of the earliest description of Shiksha as follows,

शीक्षां व्याख्यास्यामः। वर्णस्स्वरः। मात्रा बलम्। साम सन्तानः। इत्युक्तश्शिक्षाध्यायः ॥ (Tait. Upan. Shik. 2)[3]

Now, we will clearly state about Shiksha (phonetics). There are six aspects to be discussed in Shiksha:

वर्णः । varna (sounds), स्वरः । svara (accents), मात्रा । matra (short/long vowel pronunciation), बलम् । bala (the force), साम । saama (even articulation) and सन्तानः। santana (continuity in recitation) - this is termed (studied) the chapter of Shiksha.[4]

Therefore, the aim of Shiksha is to teach the pronunciation of Varna, which is pronounced from which place (throat. lips etc), what effort is required in it, in what form they are divided, how many places and efforts are there, along with the physiology of how the body and air are related to Varna, its changes in form, the number of vowels and consonants and their pronunciation.[5]

Evolution of Linguistic Concepts

The formal treatment of pronunciation and related linguistic aspects in ancient India begin with the texts called Pratisakhyas and Shikshas granthas which are said to be much later than the Vedas. The preformal speculations concerning sounds in particular and language in general are found throughout the Vedic literature. In this section we trace the evolution of linguistic units and the various components that play a role in the development of a language.[4]

अक्षरम् ॥ Akshara (Syllable)

Among the old preformal conceptions of language and linguistic units, are the notions of chandas or meters, the metrical feet, words and syllables, along with very few technical terms found in later day texts. Rigveda refers to different meters by name, e.g. Gayatri, Brhati, and Trishtubh. Vaidika chandas has two prominent features viz., fixed number of पद-s (padas or metrical foot) in a mantra/shloka and fixed number of syllables in a pada. The word, पद (pada), occasionally also meant a word or a name. However, in later day classical samskrit, the word पद (pada) referred primarily to words, and a new, though related, term, पाद (paada), began to be used for metrical foot.

Another important term, अक्षरम् (akshara) or syllable is also found widely used in the vedas. Presently, the widely used common term 'Varna' is not found in the vedic literature. In the Rigveda, it appears that a syllable formed the very basic unit or measure of language, and recognizing the divine nature of language, everything ultimately rests in the divine अक्षरम् (akshara). Rigveda, is crucial to our understanding of the earliest notions of "linguistic units":

गा॒य॒त्रेण॒ प्रति॑ मिमीते अ॒र्कम॒र्केण॒ साम॒ त्रैष्टु॑भेन वा॒कम् । वा॒केन॑ वा॒कं द्वि॒पदा॒ चतु॑ष्पदा॒ ऽक्षरे॑ण मिमते स॒प्त वाणी॑: ॥२४॥ (Rig. Veda. 1.164.24)[6]

Summary: With the Gayatri foot, he (the vedic seer) measures the Arka, with the Arka the Saman, with the Trishtubh foot the Vaka; with the two-foot and four-foot Vaka the recitation; with the syllable the seven voices.

It seems that the attention of the ancient vedic seers was focused primarily on those linguistic units which were numerically fixed in some sense. Thus, the smallest countable unit is an Akshara. For example, there are eight syllables in Gayatri chandas. It may be noted that focus was on the linguistic units fixed numerically but may contain any number of individual sounds.

वर्णः ॥ Varna (Individual Sound)

As we move to the Brahmana, Aranyaka and Upanishad texts, we find a gradual unfolding of conceptual categories. A full spectrum of linguistic units is seen in the Samkhaayna Brahmana (26.5) where we find an important conversation between Jatukarnya and Aliikayu describing the constituents of speech units.[4]

Him he asked, ‘If the performer himself should note a flaw passed over or another should call attention to it, how is that flaw to be made flawless? By repetition of the Mantra or by an oblation?’ ‘The Mantra should be recited again,’ Jatukarnya said. Him Aliikayu again asked, ‘Should one recite in full the Shastra or recitation or Nigada or offering verse or whatever else it be?’ ‘So much as is erroneous only need be repeated, a verse (rcham), or half verse (ardharcam), or quarter verse (paadam), or word (padam), or individual sound (varnam),’ Jatukarnya replied.”

Not only do we find there a clear distinction between a paada “metrical foot” and pada “word”, we also find one of the early uses of the term varna to refer to “sound”, in contrast with the older term akshara “syllable”. Thus, there is clear conceptual and terminological progress from metrical feet to words, and from syllables to individual sounds. It is significant to note the emergence of the term "varna" used in the sense of sounds, a term which only refers to colors and social classes in the earlier literature.

स्वर व्यञ्जनाश्च ॥ Svara and Vyanjana (Vowels and Consonants)

In the Aranyakas we see the further advances into pronunciation of samskrit sounds; the origin of the notion of svara, vyanjana and antastha (semi-vowel) among other pronunciations. Aitareya Aranyaka (3.2.6) reports many specific and detailed pronunciation and recitation aspects of Rigveda; it says the following about the emergence of vyanjanas

तद्वा इदं बृहतीसहस्रं संपन्नं तस्य यानि व्यञ्जनानि तच्छरीरं यो घोषः स आत्मा य ऊष्माणः स प्राणः, इति । (Aita. Aran. 2.2.4)[7]

Thus, this [collection of] a thousand Brhati verses comes into existence. Of that collection, the vyanjanas (व्यञ्जनानि । consonants) are the shareera (body), the ghosha (घोषः । vowels) is its Atma, and the ushmana (ऊष्माणः । sibilants or aspiration sounds) its Prana (vital breath).[4]

In the Chandogya Upanishad (2.22.5)[8], सर्वे स्वरा घोषवन्तो बलवन्तो वक्तव्या....। descriptions of the pronunciations evolved, such as that of svara, ghosha, sparsha etc.

These two textual references strongly reflect on the beginnings of the shastra of pronunciation in ancient India. Some notable conclusions drawn from them are as follows

- vowels are distinguished from consonants

- among consonants a distinction between the stops (sparsha varnas) and aspiration sounds (ushamanas) is made.

- notions of resonance (ghosha), openness of pronunciation (of aspirant sounds) and contact in pronunciation (of the sparsha "stop" varnas) have emerged.

- notion of semi-vowel (antastha) emerged in Aitareya Aranyaka (3.2.1).

The ancient Vedic schools developed major treatises analyzing sound, vowels and consonants, rules of combination and pronunciation to assist clear understanding, to avoid mistakes and for resonance (pleasing to the listener). These texts include Samhita-pathas and Pada-pathas of the vedas.[4]

Akshara Samaamnaaya

Over time a process of linguistic standardization of the orally received vedic literature developed and a standardized samskrit alphabet came into existence, having a specific name: Akshara samaamnaaya. This is a very important term, was continued to be used in the later formal works like Mahabhaashya, which is Maharshi Patanjali’s “Great Commentary” on the famous samskrit grammar of Maharshi Panini. The term akshara-samamnaya is important because it shows a connection with the past. The term akshara, which refers to syllables, has been used here to refer to individual sounds. As discussed earlier extension of terms has a significant impact on the terminology and meaning of words in linguistic sense.[4]

- akshara which referred to "syllables" now refers to "individual sounds" also

- pada from a "metrical foot" came to mean a "word"

- varna extended from color and social group to mean a "sound"

- samaamnaaya is used to refer to a "cumulative recitation" an oral catalogue of sounds, an ordered form of alphabet.

This period saw a loss of ancient accents and of the ability to pronounce samskrit sounds creating a gap between the orally preserved ancient texts and the current form of samskrit as well as vernacular languages. The importance of learning grammar and pronunciation was stressed on quoting the story of Vrtrasura. The Aitareya Aranyaka (3.1.5; 3.2.6) shows debates concerning sandhis in Vedic texts and whether the Vedic texts should be pronounced with or without the retroflexes श and ण. The process of standardization was meant to put an end to such doubts. The development of the technical apparatus of samkrit pronunciation seems to have come about to put an effective end to many differences and doubts. However, in the later degenerate times, the grammarians claimed, the priests stopped studying grammar and phonetics before studying the Vedas, and this led to a deplorable state of Vedic recitation.

Formal Pronunciation Texts

In the next phase, recognizing the need for an organized process of standardization, formal treatises called Pratisakhyas came into existence. The Pratisakhyas, as indicated by the etymology of the name from prati “each” + shaka “branch”, are texts where each of them relates to a particular Vedic shaka and is primarily concerned with describing the pronunciation and euphonic peculiarities of a particular Vedic text. There is also a clear linkage between the Pratisakhya tradition and the authorities mentioned in vedic texts such as the Aitareya Aranyaka. Besides this, some of the important texts in this category are the Taittiriya, Vajasaneyi pratisakhyas, the Rktantra, and the Saunakiya chaturaadhyayika.[4]

Another class of pronunciation treatises is referred to by the general term Śikṣā (referred to as Shiksha) meaning training in general, and pronunciation and recitational training in particular. The word Śikṣā appears in the Taittriya Upanishad involving detailed explanation of the training in pronunciation aspects. As a class of texts, over a hundred these Śikṣā texts have been produced by different authorities which are relatively modern to the Pratisakhyas. The most well known among these texts is the Paniniya Shiksa attributed by the tradition to the famous Sanskrit grammarian Panini. Other important Shikshas include the Vyasa, Apisali, Yajnavalkya, and the Narada shiksha. A few of these texts, such as the Paniniya shiksha and the Apisali siksha, are non-sectarian in the sense that they do not attach themselves to a particular Vedic school, and deal with the Sanskrit language in a generic way. However, most of these texts are sectarian. They are attached to particular Vedic schools, and deal with the recitation of particular Vedic texts. They often provide the most minute details of the recitational practice.[4]

वर्णोत्पत्तिः ॥ Varnotpatti

Varnas are the fundamental speech units and they are produced (वर्णोत्पत्तिः) by a complex process involving the antaranga or inner mind combined with air and articulating organs. Panini shiksha and other texts describe the physiological process by which sound (or varnas here) is produced in the human being. According to Paniniya Shiksha,

वर्णाञ्जनयते तेषां विभागः पञ्चधा स्मृतः॥9॥ स्वरतः कालतः स्थानात्प्रयत्नानुप्रदानतः। इति वर्णविदः प्राहुर्निपुणं तन्निबोधत ॥10 (Pani. Shik[9])

Varnas or Speech sounds are generated in five following ways[10]

- स्वरः ॥ Svara (Accent or Pitch) are three in number: udātta, anudātta, and Svarita.

- मात्रा ॥ Matra (Quantity or time of utterance) are three in number: ह्रस्व (hrasva = short), दीर्घ (dīrgha = long) and प्लुत (pluta = longer)

- स्थानम् ॥ Sthana (Place of articulation) are eight in number:

- प्रयत्नः ॥ Prayatna (Effort):

- अनुप्रदानम् ॥ Anupradana (Sound material)

वर्णाः ॥ Varnas or Sounds

The Vedas contain 52 characters (sounds) (13+27+8+4) as follows.[5]

- Svaras or Vowels - 13

- Sparsha or Consonants (from क to म and ल् and ल्ह्) 27

- य र ल व श ष स ह - 8

- Visarga, Anusvara, Jivhamuliya and Upadhmaniya (half Visarga signs before क and प) 4

According to Paniniya Shiksha, varnas in Samskrit are assumed to be 63 (21+25+8+4+5) in number as follows (assuming संवृत and विवृत अ to be separate they are 64 in number).[5]

- Svaras or Vowels (including hrasva, deergha and plutha etc) they are 21 in number.

- Consonants (from क to म) are 25 in number.

- य र ल व श ष स ह are 8 in number.

- Dual forms of य र ल व are 4 in number

- Visarga, Anusvara, Jivhamuliya, Upadhmaniya and Plutha लृ are 5 in number.

स्वरः ॥ Accent or Pitch

Svaras are of three types - Udaatta, Anudatta, Svarita. As seen above the Svaras or Vowels are fundamental syllables while here the Svara refers to accent or pitch. While difference in accent causes a difference in meaning in the vedic literature, accent is not given importance in classical samskrit literature. The अचः (acaḥ = vowels) are called स्वराः (svarāḥ) as they shine with 'svara' and being the 'dharma', udātta etc. are also called svarāḥ. Panini in his famous Ashtadhyayi defines svaras as follows[10]

उच्चैरुदात्तः ॥ uccairudāttaḥ ॥ १-२-२९ ॥ If the vowel is pronounced in the upper parts, it is called udātta.

नीचैरनुदात्तः ॥ nīcairanudāttaḥ ॥ १-२-३0 ॥ If the vowel is pronounced in the lower parts, it is called anudātta.

समाहारः स्वरितः ॥ samāhāraḥ svaritaḥ ॥ १-२-३१ ॥ Svarita is the combination of udātta and anudātta. (Asht. 1.2.29-31)[11]

मात्रा ॥ Matra

Following the time taken for pronunciation, the vowels (acaḥ = vowels) are named ह्रस्व (hrasva = short), दीर्घ (dīrgha = long) and प्लुत (pluta = longer). The time for these vowels is fixed by Yajnavalkya in his Shiksha[10]

एकमात्रो भवेद्ध्रस्वः द्विमात्रो दीर्घ उच्यते। त्रिमात्रस्तु प्लुतो ज्ञेयः व्यञ्जनं त्वर्धमात्रकम् ॥ १३ ॥ (Yajn. Shik. 13)

ekamātro bhaveddhrasvaḥ dvimātro dīrgha ucyate । trimātrastu pluto jñeyaḥ vyañjanaṃ tvardhamātrikam ॥ 13 ॥

If the vowel is uttered in a single mātrā or the time taken for the fall of an eyelid, then it is called hrasva, if it is two mātras, then it is dīrgha and if takes three mātras, then it is pluta. A hal (consonant) has got half-a-mātrā time. 'a' (अ) is hrasva; ā (आ) is dīrgha; and 'a3' (अ३) is pluta. For hal, 'क् क्' (k k) takes one mātrā and for a single consonant, it is half-a-mātrā. Panini in his Ashtadhyayi gives a natural example to imitate the pronunciation of hrasva, dīrgha and pluta –

ऊकालोऽच् ह्रस्वदीर्घप्लुतः ॥ १-२-२७ ॥ ūkālo'c hrasvadīrghaplutaḥ ॥ 1-2-27 ॥ (Asht. 1.2.27)[11]

A cock's sound has to be taken as an example of hrasva, dīrgha and pluta, i.e. the time taken by a cock to pronounce u, o and o3 (उ, ओ, ओ३) is the right time to follow. In Gandharvaveda (the Veda of Music), which is an Upaveda, there are seven svaras - ṣaḍja (sa), ṛṣabha (ri), gāndhāra (ga), madhyama (ma), pañcama (pa), dhaivata (da) and niṣāda (ni) – "sa-ri-ga-ma-pa-da-ni". They are born out of udatta, anudatta and svarita – explains Panini in his Shiksha:

उदात्ते निषादगान्धरौ अनुदात्त ऋषभधैवतौ। स्वरितप्रभवा ह्येते षड्जमध्यमपञ्चमाः ॥ १२ ॥ (Pani. Shik. 12)[9]

udātte niṣādagāndharau anudātta ṛṣabhadhaivatau । svaritaprabhavā hyete ṣaḍjamadhyamapañcamāḥ ॥ 12 ॥

Both niṣāda and gāndharva are born from udātta, ṛṣabha and dhaivata from anudātta, and ṣaḍja, madhyama and pañcama are from svarita.

स्थानम् ॥ Sthana

Sthanas are the places (or body parts which play a role in the production of sound) of articulation of varnas. Paniniya Shiksa defines eight places of articulation.[10]

अष्टौ स्थानानि वर्णानामुरः कण्ठः शिरस्तथा। जिह्वामूलं च दन्ताश्च नासिकोष्ठौ च तालु च॥ १३ ॥ (Pani. Shik. 13)[9]

aṣṭau sthānāni varṇānāmuraḥ kaṇṭhaḥ śirastathā । jihvāmūlaṃ ca dantāśca nāsikoṣṭhau ca tālu ca ॥ 13 ॥

There are eight places where letters are produced – chest, throat (pharynx), roof of palate, the root of the tongue, teeth, nose, both the lips and palate.

Places of Articulation of Samskrit Varnas

In the following table, the short and long vowels are represented by the short vowel; i.e. अ (a) stands for आ (ā) as well, and similarly in the case of other vowels wherever applicable.

| Letters | Place of Articulation | English Equivalent | Panini Sutra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | अ, क, ख, ग, घ, ङ, ह, ः

a, ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa, ha, ḥ |

कण्ठः (throat)

kaṇṭhaḥ |

Guttural/Velar | अकुहविसर्जनीयानां कण्ठः। |

| 2 | इ, च, छ, ज, झ, ञ, य, श

i, ca, cha, ja, jha, ña, ya, śa |

तालु (palate)

tālu |

Palatal | इचुयशानां तालु। |

| 3 | ऋ, ट, ठ, ड, ढ, ण, र, ष

ṛ, ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, ra, ṣa |

मूर्धा (roof of palate)

mūrdhā |

Cerebral/Lingual/Retroflex | ऋटुरषाणां मूर्धा। |

| 4 | ऌ, त, थ, द, ध, न, ल, स

ḷ, ta, tha, da, dha, na, la, sa |

दन्ताः (teeth)

dantāḥ |

Dental | ऌतुलसानां दन्ताः। |

| 5 | उ, प, फ, ब, भ, म, u, pa, pha, ba, bha, ma | ओष्ठौ (lips)

oṣṭhau |

Labial | उपूपध्मानीयानामोष्ठौ। |

| 6 | ञ, म, ङ, ण, न

ña, ma, ṅa, ṇa, na |

नासिका च (also nose)

nāsikā ca |

Nasal | ञमङणनानां नासिका च। |

| 7 | ए , ऐ

e, ai |

कण्ठतालु (throat and palate)

kaṇṭhatālu |

Gutturo-palatal | एदैतोः कण्ठतालु। |

| 8 | ओ, औ

o, au |

कण्ठोष्ठम् (throat and lips)

kaṇṭhoṣṭham |

Gutturo-dental | ओदौतोः कण्ठोष्ठम्। |

| 9 | व

Va |

दन्तोष्ठम् (teeth and lips)

dantoṣṭham |

Labio-dental | वकारस्य दन्तोष्ठम्। |

| 10 | क

h |

जिह्वामूलम् (root of the tongue)

jihvāmūlam |

||

| 11 | ं (अनुस्वार)

ṃ |

नासिका (nose)

nāsikā |

Nasal |

हकारं पञ्चमैर्युक्तम् अन्तस्थाभिश्च संयुतम् । औरस्यं तं विजानीयात् कण्ठ्यमाहुरसंयुतम् ॥ पाणिनीयशिक्षा, १६ ॥

hakāraṃ pañcamairyuktam antasthābhiśca saṃyutam । aurasyaṃ taṃ vijānīyāt kaṇṭhyamāhurasaṃyutam ॥ (Pani. Shik. 16)[9]

The combinations of ह-'ha' and ङ-ṅa / ञ-ña / ण-ṇa / न-na / म-ma / य-ya / र-ra / ल-la / व-va, i.e. ह्ङ-hṅa, ह्ञ-hña, ह्ण-hṇa, ह्न-hna, ह्म-hma, ह्य-hya, ह्र-hra, ह्ल-hla and ह्व-hva, are to be pronounced from the chest. The lone 'ह-ha' is born in the throat. The combination of ha + ṅa and ha + ña (ह्ङ-hṅa and ह्ञ-hña) is not present in word usages. In words like aparāhṇa (अपराह्णः), madhyāhna (मद्याह्नः), brahma (ब्रह्मा), bāhya (बाह्या), hrada (ह्रद), prahlāda (प्रह्लादः) and āhvāna (आह्वानम्), 'ha' is to be pronounced carefully, i.e. it should come from the chest.

Varnas in Samskrit Language

According to Yajnavalkya Shiksha varnas are classified into four.

- स्वराः (Svaras) (9 Vowels)

- स्पर्शाः (Sparsha) (25)

- अन्तस्थाः (Antastha) (4)

- ऊष्माणः (Ushmana) (4)

| Varnas | |

|---|---|

| अचः (acaḥ = vowels) | अ आ इ ई उ ऊ ऋ ॠ ऌ ए ऐ ओ औ अं अः |

| a ā i ī u ū ṛ ṝ ḷ e ai o au aṃ aḥ | |

| हल् (consonants) | क ख ग घ ङ च छ ज झ ञ ट ठ ड ढ ण त थ द ध न प फ ब भ म |

| ka kha ga gha ṅa ca cha ja jha ña ṭa ṭha ḍa ḍha ṇa ta tha da dha na pa pha ba bha ma | |

| य र ल व श ष स ह | |

| ya ra la va śa ṣa sa ha |

As explained in the previous section syllables (not letters) were called Akshara, meaning 'imperishable'. The aksharas or varnas are classified mainly into two types:[12]

- Svara (अचः) or Vowels which are 9 in number

- Vyanjana (हल्) or Consonants which are 33 in number

Svara aksharas are also known as prana akshara; i.e., they are the main sounds in speech, without which speech is not possible. The term Svara here refers to the Varna and is not to be confused with accent or pitch which is also called Svara. Vyanjana, i.e., consonants are incomplete and associate with vowels for pronunciation. They are also known as Prani akshara; that is, they are like a body to which life (svara) is added. They include the rest of the three types apart from Svaras varnas namely Sparsa (mentioned as Stop), Antastha and Ushmana.

Sparsa aksharas include syllables from ka to ma; they are 25 in number. Antastha aksharas include syllables ya, ra, la and va. Usman aksharas include śa, ṣa, sa and ha.

A vowel is pronounced in 18 ways (3×2×3), based on matra (time), its organ, and svara (accent) of pronunciation. However, there are some modifications. We get 18 ways of pronunciation for अ इ उ ऋ, ऌ has no Dirgha (2x2x3 = 12 ways), ए ओ ऐ औ has no Hrasva, so we get (2x2x3) twelve ways.

| Matra (मात्रा )

unit of time is a mātra |

|

|---|---|

| Organ involved in pronunciation |

|

| Svaras (Accent or Pitch) |

|

वृत्तिः॥Vṛtti

Nāradīyaśikṣā prescribes three vṛttis (procedures) called druta (द्रुता । quick), madhyama (मध्यमा । medium) and vilambita (विलम्बितम् । slow) that are useful in articulation of speech:

अभ्यासार्थं द्रुतां वृत्तिं प्रयोगार्थे तु मध्यमाम् । शिष्याणामुपदेशार्थे कुर्याद्वृत्तिं विलम्बितम् ॥ २१ ॥ (Nara. Shik. 21)

abhyāsārthaṃ drutāṃ vṛttiṃ prayogārthe tu madhyamām । śiṣyāṇāmupadeśārthe kuryādvṛttiṃ vilambitam ॥ 21 ॥

For practicing or recitation Drutavṛtti, for conversation Madhyama, and for teaching students vilambita vrtti are to be employed. In drutavṛtti, nine drops flow out of suṣumnā nāḍī, in madhyamā, twelve drops and in vilambita, sixteen drops are said to flow out of suṣumnā nāḍī.

प्रयत्नः ॥ Prayatna (Effort)

Effort (or Prayatna) of articulation is of two types for consonants,

- Bāhya Prayatna: External effort

- Abhyantara Prayatna: Internal effort

- Alpaprāna: Unaspirated

- Mahāprāna: Aspirated

- Śvāsa: Unvoiced

- Nāda: Voiced

स्वरतो वर्णतो वा अपराधम् ॥ Effects of Bad Pronunciation

Pāṇini provides a natural example for perfect pronunciation:

व्याघ्री यथा हरेत् पुत्रान् दंष्ट्राभ्यां न तु पीडयेत् । भीता पतनभेदाभ्यां तद्वद्वर्णान् प्रयोजयेत् ॥ २५ ॥

vyāghrī yathā haret putrān daṃṣṭrābhyāṃ na tu pīḍayet । bhītā patanabhedābhyāṃ tadvadvarṇān prayojayet ॥ 25 ॥

Summary: Just as a tigress carries its cubs carefully in her sharp jaws without causing any pain to them, afraid about their falling down or being cut accidentally, similarly one should pronounce letters like that (using the same precautions). Pāṇinī further cautions against any mispronunciation in terms of accent or letter and asserts that such a usage would bring about disastrous consequences to the yajamana:[10]

मन्त्रो हीनः स्वरतो वर्णतो वा मिथ्याप्रयुक्तो न तमर्थमाह । स वाग्वज्रो यजमानं हिनस्ति यथेन्द्रशत्रुः स्वरतोऽपराधात् ॥ ५२ ॥

mantro hīnaḥ svarato varṇato vā mithyāprayukto na tamarthamāha । sa vāgvajro yajamānaṃ hinasti yathendraśatruḥ svarato'parādhāt ॥ 52 ॥

A mantra that is defective in terms of accent or letter would not be useful as it does not convey the intended meaning. Moreover it will become a weapon as good as the diamond-weapon of Indra, and boomerangs against the doer. This is what happened when the mantra 'indraśatruḥ vardhasva' was employed with a different accent. The following story from Taittirīyasaṃhitā (2.5.2.1), and Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 1.5.2.10 (Shuklayajurveda) is being referred to by the quoted mantra –

अथ यदब्रवीत् – इन्द्रशत्रुर्वर्धस्वेति तस्मादु हैनमिन्द्र एव जघान। अथ यद्ध शश्वदवक्ष्यत् – इन्द्रस्य शत्रुर्वर्धस्वेति शश्वदुह स इन्द्रमेवाहनिष्यत् ।

atha yadabravīt – indraśatrurvardhasveti tasmādu hainamindra eva jaghāna. atha yaddha śaśvadavakṣyat – indrasya śatrurvardhasveti śaśvaduha sa indramevāhaniṣyat

Visvarūpa was the son of Tvaṣṭā. The former was killed by Indra. Tvaṣṭā wanted to avenge and commenced a sacrifice called 'abhicārahoma' in order to have a son who can kill Indra. Then, while praying to Fire-God (āhavanīyāgni) a mantra, i.e. 'svāhendraśatrurvardhasva', which means – "O! Fire-God! Prosper as a person who can kill Indra" was guessed. In the mantra 'śatru' means destroyer and in such a case it should be employed with 'antodāttasvara' as it is a Tatpuruṣasamāsa, i.e. indrasya śatruḥ. But the priest employed the same mantra as 'ādyudātta', which is a Bahuvrīhisamāsa, which means 'be born as one, who has got Indra as the destroyer'. As a result Indra became the destroyer of Vṛtra, who was killed soon after his birth. Therefore, in order to avoid such repercussions, one should be careful in his speech actions.

वेदपाठकगुणाः ॥ Qualities of a Vedapathaka

In the recitation of vedamantras, just as svara or varna doshas leading to disastrous consequences are described these granthas also explain the beneficial effects. In all shikshas it has been emphasized that proper, accurate, accented pronunciation of the veda mantras must be adhered to obtain the desired results. Vyasa shiksha describes four basic qualities of a Vedapathaka[13]

सुव्यक्तस्सुस्वरो धैर्यं तच्चित्तत्वं चतुर्गुणाः । एतद्युक्तः पठेद्वेदं स वेदफलमश्नुते ॥ (Vyas. Shik. 503)

Four basic requisites for obtaining the desired results of recitation of vedamantras are enumerated: सुव्यक्तम् (suvyaktam) i.e., recitation according to rules of ucchaarana, सुस्वरः (susvara) i.e., pronouncing according to the rules of svara in a nasal free voice, धैर्यं (dhairyam) i.e., giving undivided attention pronouncing with confidence (avoiding shaky voice), तच्चित्तत्वं (tacchitatvam) i.e., (student) being completely absorbed in the vedic recitation. Acharyas are cautioned to watch for the above mentioned four qualities in students both in adequate proportion amount and combination. The Acharya himself must have the ability to distinguish the svara and varna doshas, thus should have exceptional hearing abilities to weed out the errors and correct them in a student. Probably because of this requirement the study is referred to as tapasya, always requiring the concentration of mind and well concerted assiduous efforts in listening as well as in erudition.

ध्वनिस्स्थानञ्च करणं प्रयत्नः कालता स्वरः। देवताजातिरेतैश्च वर्णा ज्ञेया विचक्षणैः ॥

पदक्रमविशेषज्ञो वर्णक्रमविचक्षणः । स्वरमात्राविभाज्ञो गच्छेदाचार्यसम्पदम् ॥ (Vyas. Shik. 511-512)[13]

One who understands and discerns the dhvani (sound) sthanas (place of articulation), karanas (articulators), prayatnas (efforts), kalata (notion of time), devatas associated with varnas, the grouping (jati), is an expert in padakrama and varnakrama and knows the svaras and matras - such a person attains the position of Acharya. Paniniya Shiksha mentions the following six qualities required of a Vedapathaka.[5]

माधुर्यमक्षरव्यक्तिः पदच्छेदस्तु सुस्वरः । धैर्यं लयसमर्थं च षडेते पाठका गुणाः ।। (Pani. Shik. 33)

They are:

- माधुर्यम् - to speak sweetly

- अक्षरव्यक्तिः - Clear pronunciation of letters.

- पदच्छेदः - Speaking with appropriate word breaks.

- सुस्वरः - To speak with optimal sound.

- धैर्यं - Speaking calmly.

- लयसमर्थं - Speaking rhythmically (not noise).

Paniniya Shiksha also mentions the following six doshas or negative qualities to be avoided by a Vedapathaka.[5]

गीती शीघ्री शिरःकम्पी तथा लिखितपाठकः ।

अनर्थज्ञोऽल्पकण्ठश्च षडेते पाठकाधमाः ।। (Pani. Shik. 32)

Pathaka-adhamas are those who recite with the following six doshas:

- गीती - to recite in a singing manner

- शीघ्री - to recite in a fast manner

- शिरःकम्पी - shaking the head while reciting

- लिखितपाठकः - read written instead of chant

- अनर्थज्ञः - recite without the knowledge of the meaning

- अल्पकण्ठः - recite an incompletely memorized mantra in a low voice

Pratisakhyas are the oldest Siksa textbooks intimately connected to shakas of the four Vedas. Although specific in subject matter their contribution in protecting the vedic form, is as invaluable as that of Vyakarana and Siksha texts. Their textual content differs from Vyakarana and Shiksha granthas in that they deal exclusively with the peculiarities of that particular veda shaka in the areas of svaras, sandhis and other pronunciation aspects and are thus as old as the Vedas themselves.[2] Later Siksa texts are systematic, and often titled with suffix "Siksa", such as the Naradiya-Siksa, Vyasa-Siksa, Paniniya-Siksa and Sarvasammata-Siksa.

The Pratishakhyas, which evolved from the more ancient Vedic padapathas, deal with the manner in which the Vedas are to be enunciated. There are separate Pratishakhyas for each Veda and they are composed either in sutra or shloka formats. They complement the books called Shiksha written by various authorities. Several Pratishakhyas have survived into the modern era:[14]

- Rigveda-Pratishakya: Composed by Shaunaka

- Vajasaneya-Pratishakhya: Composed by Katyayana

- Taittiriya (Krishna Yajurveda) Pratishakhya

- Samaveda-Pratishakhyas: Four of them are - Rig-tantra, Samatantra, Akshara-tantra, Pushpa sutras

- Atharvaveda-Pratishakhya (Shaunakiya shakha)

The Shiksha Texts and the Pratishakhyas led to great clarity in understanding the surface structure of language. For clarity of pronunciation, they broke up the large Vedic compounded structures into word stems, prefixes, and suffixes. Certain styles of recitation, such as the vikriti pathas, involved switching syllables, repeating the last word of a line at the beginning of the next, and other permutations. In the process, a considerable amount of morphology is discussed, particularly regarding the combination of sequential sounds, which leads to the modalities of sandhi.

Shiksha Granthas