Difference between revisions of "Sukha and Ananda (सुखानन्दश्च)"

(→Upanishadic Perspectives of Ananda and Sukha: Added content) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Ananda (Samskrit: आनन्दः) is a term of great significance in Indian philosophical traditions and in other cultures. Across time and cultures, human beings attached great value to Ananda, and have been trying to find it. In this process, philosophies have been developed, books have been written and teachings have been given. The ideas of happiness are closely linked with the larger framework of reality and human nature which one carries in their mind. Conceptualization of the nature of happiness and well-being primarily depend on the worldview one holds that lead to differing assumptions on the nature of reality and of human nature. It has varied across cultures on a spectrum ranging from hedonic to transcendent viewpoints.<ref name=":4">Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Happiness and well-being in Indian tradition," ''Psychological Studies'' 51, no. 2-3, (2006): 105-112.</ref> Happiness is not only an emotion but refers to living a good life, experiencing well-being and enjoying a good quality of life. Sukha (Samskrit: सुखम्), in contrast, is discussed in terms of worldly and heavenly pleasures as against Ananda which signifies eternal bliss which accompanies the end of the rebirth cycle (punarjanma rahityam). | Ananda (Samskrit: आनन्दः) is a term of great significance in Indian philosophical traditions and in other cultures. Across time and cultures, human beings attached great value to Ananda, and have been trying to find it. In this process, philosophies have been developed, books have been written and teachings have been given. The ideas of happiness are closely linked with the larger framework of reality and human nature which one carries in their mind. Conceptualization of the nature of happiness and well-being primarily depend on the worldview one holds that lead to differing assumptions on the nature of reality and of human nature. It has varied across cultures on a spectrum ranging from hedonic to transcendent viewpoints.<ref name=":4">Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Happiness and well-being in Indian tradition," ''Psychological Studies'' 51, no. 2-3, (2006): 105-112.</ref> Happiness is not only an emotion but refers to living a good life, experiencing well-being and enjoying a good quality of life. Sukha (Samskrit: सुखम्), in contrast, is discussed in terms of worldly and heavenly pleasures as against Ananda which signifies eternal bliss which accompanies the end of the rebirth cycle (punarjanma rahityam). | ||

| Line 29: | Line 27: | ||

== सुखम् आनन्दं वा ॥ Sukha Vs Ananda == | == सुखम् आनन्दं वा ॥ Sukha Vs Ananda == | ||

| − | Happiness is one of the English terms for ''ananda'', and it takes two shades based on materialistic or non-materialistic views. The nearest and approximate equivalent of the term, ''ananda'', in English is ''bliss'', when it is associated with spirituality. This is distinguished from ''sukha'', the happiness of a mundane variety. The opposite of sukha is dukkha (sorrow and suffering). Although meaning in life is often centered in the extrinsic pursuit of sukha, a higher meaning of life needs to be focused intrinsically in ananda.<ref>Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Meaning and Well-being: Indian Perspectives," ''Journal of Constructivist Psychology'' 30:1, 63-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2015.1119087</ref> Man instinctively has a natural attraction to sensory gratification, desires and attachment. He strives for pleasure. Pleasure is sense related. It is evanescent and ephemeral. Bliss is more stable and spiritual, because it is anchored in consciousness. One’s pleasure may lead to suffering of others but bliss spreads happiness all around.<ref>Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) ''Psychology in the Indian Tradition.'' London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 305-306</ref> | + | Happiness is one of the English terms for ''ananda'', and it takes two shades based on materialistic or non-materialistic views. The nearest and approximate equivalent of the term, ''ananda'', in English is ''bliss'', when it is associated with spirituality. This is distinguished from ''sukha'', the happiness of a mundane variety. The opposite of sukha is dukkha (sorrow and suffering). Although meaning in life is often centered in the extrinsic pursuit of sukha, a higher meaning of life needs to be focused intrinsically in ananda.<ref>Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Meaning and Well-being: Indian Perspectives," ''Journal of Constructivist Psychology.'' (2016) 30:1, 63-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2015.1119087</ref> Man instinctively has a natural attraction to sensory gratification, desires and attachment. He strives for pleasure. Pleasure is sense related. It is evanescent and ephemeral. Bliss is more stable and spiritual, because it is anchored in consciousness. One’s pleasure may lead to suffering of others but bliss spreads happiness all around.<ref>Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) ''Psychology in the Indian Tradition.'' London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 305-306</ref> |

According to Ayurveda, sukha (happiness) is a state without physical and psychical ailments, where a person has energy and strength to perform his duties, and knowledge to know what is right and wrong, is able to use his senses and enjoy from them, and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.23). Useful life (hitāyu) is one where the person attends to well-being of others, controls his passions, shares his knowledge and wealth with others and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.26).<ref>Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) ''Psychology in the Indian Tradition.'' London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 212</ref> | According to Ayurveda, sukha (happiness) is a state without physical and psychical ailments, where a person has energy and strength to perform his duties, and knowledge to know what is right and wrong, is able to use his senses and enjoy from them, and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.23). Useful life (hitāyu) is one where the person attends to well-being of others, controls his passions, shares his knowledge and wealth with others and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.26).<ref>Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) ''Psychology in the Indian Tradition.'' London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 212</ref> | ||

| Line 94: | Line 92: | ||

=== Biological Implications of Pleasure and Happiness === | === Biological Implications of Pleasure and Happiness === | ||

| − | Research<ref name=":8">Røysamb, Espen & Tambs, Kristian & Reichborn-Kjennerud, Ted & Neale, Michael & Harris, Jennifer. (2004). Happiness and Health: Environmental and Genetic Contributions to the Relationship Between Subjective Well-Being, Perceived Health, and Somatic Illness | + | Research<ref name=":8">Røysamb, Espen & Tambs, Kristian & Reichborn-Kjennerud, Ted & Neale, Michael & Harris, Jennifer. (2004). Happiness and Health: Environmental and Genetic Contributions to the Relationship Between Subjective Well-Being, Perceived Health, and Somatic Illness. ''Journal of personality and social psychology.'' 85. 1136-46. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1136. </ref> has suggested that happiness has genetic factors that account for substantial amounts of individual variation in well-being and health conditions. Despite the mounting evidence that genes play an important role in the etiology of well-being, personality, mental health, and physical illness, genetic and environmental influences on the covariance between SWB and physical health have been largely unexplored.<ref name=":8" /> In order to help understand happiness and alleviate the suffering, neuroscientists and psychologists have started to investigate the brain states associated with happiness components and to consider the relation to well-being. While happiness is in principle difficult to define and study, psychologists have made substantial progress in mapping its empirical features, and neuroscientists have made comparable progress in investigating the functional neuroanatomy of pleasure, which contributes importantly to happiness and is central to our sense of well-being.<ref>Kringelbach, M. L., & Berridge, K. C. (2010). The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure. ''Social research'', ''77''(2), 659–678.</ref> |

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+Comparison between Pleasure and Happiness<ref name=":6" /> | |+Comparison between Pleasure and Happiness<ref name=":6" /> | ||

| Line 149: | Line 147: | ||

|Evaluative | |Evaluative | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Upanishadic Perspectives of Ananda and Sukha == | ||

| + | In various Upanishads, the Taittriya, Brhdaranyaka, Mandukya, Chandogya, and Katha Upanishads, and in the Bhagavadgita, there are interesting discussion sections dealing extensively about the happiness and well-being of an individual.<ref name=":0" /> The Vedic and Upanishadic seer and sages emphasised on realising that which is eternal (nitya) and permanent (satya), rather than going after anything that is momentary (kshanika) and that is liable to undergo decay and destruction (kshara) or impermanent (mithya). They understood ''Ananda'', bliss, as the original condition of human beings and characterize Atman, the 'pure consciousness' or transcendental Self. It is the Ananda of sat-chit-ananda the different from the ''ananda'' of Anandamaya kosha that refers to the intrinsic condition of blissfulness. Therefore Ananda actually refers to a state of consciousness, characterised by positive feeling, which is not dependent on any object or events of external reality. Thus the experience of ananda, bliss, is a qualitatively different sense of positive state and well being from that is associated with other sheaths, koshas. Hence, a person who has an expanded state of consciousness evaluates his/her well being as ananda. The self-sense beyond anandamaya kosha is the transcendent Self, [[Atman (आत्मन्)|Atman]], pure consciousness, which is a positive state characterized as ''shaanti'', that is a sense of sublime peace and quietude.<ref name=":22">Salagame. K. Kiran Kumar, ''An Indian Conception of Well Being''. In Henry, J. (Ed) [https://www.ipi.org.in/texts/kirankumar/kk-indian-conception-ofwellbeing.php European Positive Psychology Proceedings] (2003)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Tattriya Upanishad and Anandamaya Kosha ==== | ||

| + | The second adhyaya in Taittriya Upanishad, is named as Brahmanandavalli. It deals with the Ananda of Sat-chit-Ananda, the attributes of [[Brahman (ब्रह्मन्)|Brahman]]. In this Upanishad, we find a detailed discussion on the nature of happiness and realizing it as the innermost core of one's being. It is also the core of human personality around which the individual [[Jiva (जीवः)|Jiva]], exists and functions. However, there are many layers or sheaths around this core which impede the experience of the original condition.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The sheaths, [[Panchakosha (पञ्चकोषाः)|Panchakoshas]], that cover are five in number viz., Annamaya - physical, Prāṇamaya – the vital, Manomaya – the mental, Vijñānamaya – the intuitive, and Ānandamaya – the blissful.<ref name=":22" /> A few interesting points about happiness (sukha) associated with these sheaths. | ||

| + | |||

| + | # Different types of emotions, positive and negative, are associated with the first three koshas (annamaya, pranamaya and mannomaya koshas). Many people feel their identities or self-sense with these three koshas, and remaining established at this level, they evaluate ill-being or well-being within this limited framework. | ||

| + | # At the remaining two koshas (vijnanamaya and anandamaya koshas) a person can experience only a positive state. Some persons either spontaneously or through induction from meditation, yoga and such other practices are able to move beyond the above three sheaths and narrow self-definitions. Spontaneous peak experiences, drug-induced states, and ecstatic and mystic experiences are instances of transcendence of the limitations of first three koshas.<ref name=":22" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Bhruguvalli, introduces the threefold concept of priya, moda, and pramoda in the imagery of a bird. Here, ‘priya’ is its head, ‘moda’ and ‘pramoda’ are its left and right wings respectively, ‘ānanda’ is the soul and ‘brahman’ is its base. Adi Shankaracharya, while commenting on this section, shares an interesting insight pertaining to happiness. He notes that the happiness experienced, when an object is seen or perceived with a sense of wanting it is ‘priya’,when the object is possessed, it is ‘moda’ and when enjoyed/utilized, it is ‘pramoda’.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Brhdaranyaka Upanishad and Sarva Priya Bhavana ==== | ||

| + | In Maharshi [[Yajnavalkya Maitreyi samvada (याज्ञवल्क्यमैत्रेय्योः संवादः)|Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi Samvada]], Maitreyi enquires about acquiring means through which she could be immortal. At the end of a detailed dialogue that ensues between them, [[Yajnavalkya (याज्ञवल्क्यः)|Yajnyavalka]] utters the oft discussed phrase of the Upanishad <blockquote>न वा अरे सर्वस्य कामाय सर्वं प्रियं भवति, आत्मनस्तु कामाय सर्वं प्रियं भवति । na vā are sarvasya kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati, ātmanastu kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati ।’(Brhd. Upan. 2.4.5)</blockquote>It means, ‘for the sake of the self everything else becomes dear or desirable.’<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Mandukya Upanishad and Ananda in Sushupta Avastha ==== | ||

| + | In the Māṇḍūkya Upanishad, the self of the individual is described using two words ‘ānandamaya’(filled with bliss) and ‘ānandabhuk’ (experiencer of bliss). However, in the previous line in the concerned section, the self is qualified as the being in the dreamless state with no desires unfulfilled.<ref name=":0" /><blockquote>सुषुप्तस्थान एकीभूतः प्रज्ञानघन एवानन्दमयो ह्यानन्दभुक् चेतोमुखः प्राज्ञस्तृतीयः पादः ॥ ५ ॥ (Mand. Upan. 5)<ref>[https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%AE%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%A3%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A1%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D Mandukya Upanishad]</ref></blockquote>At the time of deep sleep (''sushupti''), the mind is free from those miseries of the efforts made on account of the states of the mind being involved in the subject-object relationship: therefore, it is called the "Anandamaya", that is, endowed with an abundance of bliss. But this is not the Ananda as the attribute of Brahman, because once the perceiver associates deep sleep with the Upadhi of the causal state (karana sharira). In common parlance, one, free from efforts, is called happy and enjoyer of Ananda. As the Prajna (undifferentiated consciousness) enjoys this state of deep sleep which is entirely free from all efforts, therefore it is called the "Anandabhuk’ (the experiencer of bliss). That the Prajna, in deep sleep, enjoys bliss is viewed from waking state.<ref>Swami Nikhilananda, trans, ''The Mandukyopanishad with Gaudapada's Karika and Sankara's Commentary'', Mysore: Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama, (1949) 23-26</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Chandogya Upanishad and Boundlessness ==== | ||

| + | In the seventh adhyaya, in Maharshi Narada and Sanathkumara's samvada, Sanathkumara says that happiness lies in the fullness or vastness and not in a sense of limitedness.<ref name=":0" /><blockquote>यत्रान्यत्पश्यत्यन्यच्छृणोत्यन्यद्विजानाति तदल्पं यो वै भूमा तदमृतमथ ... (Chand. Upan. 7.24)<ref>Chandogya Upanishad ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%9B%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%A8%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D/%E0%A4%85%E0%A4%A7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%83_%E0%A5%AD Adhyaya 7])</ref></blockquote>Meaning: When you are not using your organs of perception through seeing or hearing and you are free from cognizing, which are limited, that state is Bhuma which is unlimited exalted state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The word 'bhuma', is further explained as the blissful state or expansive state. This is the state when the mind is not constricted by a stream of unending thoughts and is free of being confined.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Katha Upanishad and happiness beyond worldly pleasures ==== | ||

| + | In Kathopanishad, where we find the [[Yama Nachiketa Samvada (यमनचिकेतसोः संवादः)|Yama Nachiketa samvada]], we get rich insights in understanding the concept of happiness. [[Yama Deva (यमदेवः)|Yama]] tries to lure Nachiketa with various forms of riches and sensual pleasures. Nachiketa emphatically states that 'wealth cannot bring him happiness' and persists in seeking the knowledge of immortality from Yama. This Upanishad treats the matter of worldly pleasures (sukha) distinctly and secondary to the higher form of happiness or Ananda, which is the knowledge of the true self.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Elsewhere in this Upanishad, we find that inactivity of all the cognizing apparatus leads to an exalted state.<blockquote>यदा पञ्चावतिष्ठन्ते ज्ञानानि मनसा सह । बुद्धिश्च न विचेष्टते तामाहुः परमां गतिम् ॥ १० ॥ (Kath. Upan. 2.6.10)<ref>Katha Upanishad ([https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%A0%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%8D/%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%80%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%A7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%83/%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%83%E0%A4%A4%E0%A5%80%E0%A4%AF%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%B2%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B2%E0%A5%80 Adhyaya 3 Valli 3])</ref></blockquote>The meaning being, when the five sense organs are not functioning when the mind and the intellect have become inactive, that is the exalted state or blissful state to attain.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

== Several features of Happiness == | == Several features of Happiness == | ||

| Line 194: | Line 221: | ||

== Components of happiness == | == Components of happiness == | ||

| + | A majority of researchers now agree that happiness is most likely composed of three related components: positive affect, absence of negative affect and satisfaction with life as a whole.<ref>Lu, Luo. Personal or Environmental Causes of Happiness: A Longitudinal Analysis, ''The Journal of Social Psychology'', (1999), 139 (1), 79-90</ref> | ||

| + | |||

Most of the research done so far in the field of Psychology has focused on what the reasons are for a person to be happy or the external factors contributing to happiness. Large surveys have come up with the components of happiness factor such as:<ref name=":1">Hemachand, Lata. The Concept of Happiness in the Upanishads and its Relevance to Therapy, ''Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology'', 2021, 48, no. 2, 123-130</ref> | Most of the research done so far in the field of Psychology has focused on what the reasons are for a person to be happy or the external factors contributing to happiness. Large surveys have come up with the components of happiness factor such as:<ref name=":1">Hemachand, Lata. The Concept of Happiness in the Upanishads and its Relevance to Therapy, ''Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology'', 2021, 48, no. 2, 123-130</ref> | ||

| Line 203: | Line 232: | ||

# self esteem | # self esteem | ||

| − | The objectives of Indian texts such as Upanishads, on the other hand, give a suggestion and a way to the seeker to look within. They encourage reaching the state of Ananda through spiritual practices or mental exercises which are within the control of the individual rather than the external forces which are not under his or her control.<ref name=":1" /> | + | The objectives of Indian texts such as Upanishads, on the other hand, give a suggestion and a way to the seeker to look within. They encourage reaching the state of Ananda through spiritual practices or mental exercises which are within the control of the individual rather than the external forces which are not under his or her control.<ref name=":1" /> |

== Misconceptions about happiness == | == Misconceptions about happiness == | ||

Latest revision as of 16:57, 3 April 2023

Ananda (Samskrit: आनन्दः) is a term of great significance in Indian philosophical traditions and in other cultures. Across time and cultures, human beings attached great value to Ananda, and have been trying to find it. In this process, philosophies have been developed, books have been written and teachings have been given. The ideas of happiness are closely linked with the larger framework of reality and human nature which one carries in their mind. Conceptualization of the nature of happiness and well-being primarily depend on the worldview one holds that lead to differing assumptions on the nature of reality and of human nature. It has varied across cultures on a spectrum ranging from hedonic to transcendent viewpoints.[1] Happiness is not only an emotion but refers to living a good life, experiencing well-being and enjoying a good quality of life. Sukha (Samskrit: सुखम्), in contrast, is discussed in terms of worldly and heavenly pleasures as against Ananda which signifies eternal bliss which accompanies the end of the rebirth cycle (punarjanma rahityam).

परिचयः ॥ Introduction

The mystery of happiness has preoccupied philosophers, psychologists and the whole human race. Fundamentally, everyone is compelled to identify happiness, worldly or transcendent in nature, as a 'virtue' because it is something everyone wants in a positive way. The pursuit of happiness has been the axiomatic reference of all human endeavors across cultures and timelines. The need to seek 'happiness' and be 'happy' through all one's actions is universally acknowledged as the main motivating force in the lives of people.[2]

Currently, the study of well-being (Svasthya) and happiness (ananda, sukha) has acquired central focus in the discipline of psychology and more so in positive psychology as a subject.[1]

At present, there are two dominant approaches to human happiness and well‐being:

- Hedonic perspectives

- Eudaimonic perspectives

The hedonic perspective with its roots in Hedonism – an ancient school of thought which argues that pleasure is the only intrinsic good, seeks to maximize one’s happiness by maximizing one’s pleasure and avoiding displeasures. Subjective Well-being (SWB) has been associated with the hedonistic approach. Wellbeing in itself refers to the optimal psychological experience and functioning of the individual. As it involves people evaluating themselves subjectively, the extent to which they experience a sense of wellness is termed as Subjective Well-being (SWB).[2]

The eudaimonic perspective of happiness is defined as the highest good that one seeks and one ought to seek as the end in itself and not as a means to any other end. It results from a life based on virtuousness and contemplation. Psychological well-being (PWB) is the counterpart of SWB in the eudaimonic tradition.[2]

In Indian traditions we quite often hear about the chants - सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः। let all be happy and लोकाः समस्ताः सुखिनो भवन्तु। lokāḥ samastāḥ sukhino bhavantu॥ let all the beings in all worlds be happy. Here the reference is to सुखम् in the sense of happiness.[3] Within Indian society itself we have both material and spiritual worldviews espoused in ancient times leading to different perspectives, hedonic, collective and transcendental.[1]

व्युत्पत्तिः ॥ Etymology and Definitions

According to Shabdakalpadhruma[4] आनन्दः (ānandaḥ) means आह्लादः which in general means a state of happiness, joy, delight, pleasure. In Taittriya Upanishad, आनन्दं ब्रह्मणो विद्वान्न बिभेति कदाचन, and in Shatapata Brahmana, (10.3.5.13) आनन्द एवास्य विज्ञानमात्माऽऽनन्दात्मानो हैवं सर्वे देवाःananda refers to supreme bliss of felicity.[5] It is used in the sense of God, Supreme Spirit (ब्रह्मन्) (said to be n. also in this sense; cf. विज्ञानमानन्दं ब्रह्म Bṛi. Up.3.9.28.).[5]

The synonyms used for आनन्दः (ānandaḥ) are given as आबन्दथुः (Abandathu), शर्म्म (Sharma), शातं (Shanta), सुखं (Sukha), सुत् (Sut), प्रीतिः (Priti), प्रमोदः (Pramoda), हर्षः (Harsha), प्रमदः (Pramada), आमोदः (Amoda), समदः (Samada) as per Amarakosha.[4]

‘Happy’ as an adjective has three broad meanings: (1) fortunate, lucky; feeling or expressing pleasure, contentment, satisfaction, etc.; (2) (in polite formulas) pleased; (3) (of language, conduct, suggestion) well-suited to the situation. ‘Happiness' is used as a noun to convey the first meaning (Hornby et al. 1948, cited in Lu 2001). While, it is true that the feelings of being fortunate and happy are intimately connected and in some instances synonymous, the term does not cover the various shades of the actual experience itself, nor does it provide any significant insight into the psychological processes that accompany the state of happiness.[3] Happiness is a state of well-being, characterized by feelings of contentment and satisfaction with one's life or current situation.[6]

Similarly, in Indian languages also, there are many terms used for happiness, like bhoga, sukha, santoṣa, harṣa, ullāsa, ānanda, trpti, tuṣhti, śubha, mangala, kalyāṇa, śreyas, preyas, śānti, ārogya, swāsthya, sthitaprajñatā.[1] Of all these, the word sukha is most commonly used to denote happiness as reflected in the invocations like "lokāḥ samastāḥ sukhino bhavantu."[3]

सुखम् आनन्दं वा ॥ Sukha Vs Ananda

Happiness is one of the English terms for ananda, and it takes two shades based on materialistic or non-materialistic views. The nearest and approximate equivalent of the term, ananda, in English is bliss, when it is associated with spirituality. This is distinguished from sukha, the happiness of a mundane variety. The opposite of sukha is dukkha (sorrow and suffering). Although meaning in life is often centered in the extrinsic pursuit of sukha, a higher meaning of life needs to be focused intrinsically in ananda.[7] Man instinctively has a natural attraction to sensory gratification, desires and attachment. He strives for pleasure. Pleasure is sense related. It is evanescent and ephemeral. Bliss is more stable and spiritual, because it is anchored in consciousness. One’s pleasure may lead to suffering of others but bliss spreads happiness all around.[8]

According to Ayurveda, sukha (happiness) is a state without physical and psychical ailments, where a person has energy and strength to perform his duties, and knowledge to know what is right and wrong, is able to use his senses and enjoy from them, and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.23). Useful life (hitāyu) is one where the person attends to well-being of others, controls his passions, shares his knowledge and wealth with others and is virtuous (Caraka Saṁhitā, 1.30.26).[9]

On the other hand, AdvaitaVedānta conceives jiva (person) as a multi-layered entity composed of five nested sheaths, the Panchakoshas, with ananda (blissfulness) at the core (ānandamaya). The Taittiriya Upanishad (2.8) estimates the Bliss of Brahman/Ātman to be 100 quintillion times higher than what a young, well-endowed human being can enjoy.[10]

A cursory glance of the two terms that have been used to denote the concept of happiness, is as follows[2]

- Ānanda (आनन्दम्): This term is made of the prefix ‘Ā’ and the root ‘nand’ meaning rejoicing. Happiness, joy, enjoyment, sensual pleasure, pure happiness are the meanings of the term as provided by Monier Williams. It is the most commonly used word in Vedantic literature. Generally, it covers the entire range of happiness at various levels but mainly refers to the ultimate happiness or bliss. It is also one of the terms used to describe the essential nature of the Self along with Sat (Existence) and Cit (Consciousness).

- Sukha (सुखम्): This is the other most common term for happiness in Vedantic literature and folk culture. It means pleasant, comfort, easiness, prosperity, pleasure, happiness etc. according to the Monier Williams dictionary.

In common language the terms sukha and Ānanda are used synonymously. However, it must be noted that sukha belongs to a set of concepts where dualities exist i.e. dukha (pain, sorrow, suffering etc.) stands in contrast to sukha, whereas Ānanda is beyond sukha as it transcends both sukha and dukha. As such there is no term that stands in anti-thesis to the experience of Ānanda.[2]

Happiness is a mental or emotional state of well-being characterized by positive or pleasant emotions.

आनन्दस्त्रिविधः ॥ Three kinds of Ananda

Panchadasi, a Vedantic text by Swami Vidyaranya, describes three kinds of Ananda.[2]

आनन्दस्त्रिविधो ब्रह्मानन्दो विद्यासुखं तथा । विषयानन्द इत्यादौ ब्रह्मानन्दो विविच्यते ॥ ११॥ (Panchadasi 11.11)[11]

Meaning: Ananda is said to be of three kinds, viz., Brahmananda, Vidyasukha, and Vishayananda.

The text further explains the three as follows.

- ब्रह्मानन्दः ॥ Brahmananda - transcendental happiness which is regarded as the highest form of happiness or bliss that a person can experience. Atmananda (bliss of Atma/Self) is described to those desiring to know the truth about Brahman. All things including wife, sons and wealth are loved not for their sakes but for the sake of Self. Self is never loved for the sake of anything else. Love for the Self is not the same as desire, for it exists in the absence and presence of desires. More information about this can be obtained from Yajnavalkya Maitreyi Samvada. Similarly in the states of Samadhi, in Yogananda (bliss of Yoga), sleep etc., secondless Brahman is experienced.[12]

- विद्यासुखम् ॥ Vidyasukha (Jnanananda) - happiness due to knowledge is a modification of intellectual operation. It is of four kinds characterized by (1) absence of sorrow, (2) fulfillment of desires, (3) satisfaction arising from accomplishment of all deeds that have to be done and (4) realization of all that need to be realized.[13]

- विषयानन्दः ॥ Vishayananda - happiness derived from material objects is described in this section. It is preliminary to and a part of Brahmananda, however other creatures enjoy only a mere trace of it. Like the happiness due to knowledge, that due to material objects is also a modification of the intellectual operation. Material operations are of three kinds - calm (Satvic), active (Rajasic) and ignorant (Tamasic). [14]

Considering the idea of happiness and sukha in Panchadasi, the Vedantic tradition, and examining the later texts on dramaturgy (Alankara Shastra) and aesthetics (Natya Shastra) such as Dhvanyaloka and Natyashastra by Bharatamuni, researchers[2] in Indian Psychology came up with a broad classification of happiness into three categories to convey the quintessence of Indic insight on happiness. They are (in the order of gross to subtle):

- Vishayananda – Sensual/Material happiness

- Kavyananda – Aesthetic happiness

- Brahmananda – Existential/transcendental happiness

विषयानन्दः ॥ Vishayananda (Hedonistic happiness)

According to the authors, [2] Vishaya refers to objects, and Vishayananda can be equated to hedonistic happiness, which is experienced by an individual coming in contact with objects of desire. Usually, it is the pleasure associated with either yearning, possessing, consuming, etc. of material objects. It is the grossest form of happiness. The Gita (5.22) notes that such pleasurable experience based on the sense-object contact is momentary or short lived, and may even leave the person with a sense of wanting and lack and consequently cause pain and suffering once the external stimulus fades.

ये हि संस्पर्शजा भोगा दुःखयोनय एव ते । आद्यन्तवन्तः कौन्तेय न तेषु रमते बुधः ॥ ५-२२॥ (Bhag. Gita. 5.22) ye hi saṃsparśajā bhogā duḥkhayonaya eva te ādyantavantaḥ kaunteya na teṣu ramate budhaḥ

Moreover, the intensity of happiness experienced is said to reduce with prolonged exposure to the source such as the Rājasika and tāmasika sukha. It must be noted that the Indic tradition does not negate the role and necessity of material happiness. However, it very clearly brings out the limitations of such happiness and persuades the individual to go beyond immediate gratification and seek a deeper and more lasting happiness.

काव्यानन्दः॥ Kavyananda (Eudaimonic happiness)

Kavya literally means the work/product of a "kavi" - visionary, a seer, a poet, an artist etc., which involves talent, a particular skill, and grace. Similar to eudaimonic happiness, this is experienced in a situation where the individual is called to respond to a challenge and in response every individual expresses certain potentialities within and actualizes them. In other words, this is the kind of happiness a person experiences in self-actualization. Here, the external situation calls upon the person to rise above his/her ordinary comfort zone and excel in the required task and in response the person's internal system rises to the occasion successfully. The situation or objects outside act as motivators or stimulants. Consequently, there is a sense of fulfilment, accomplishment, and enhanced self-worthiness that accompanies such an experience which could be self-directed as well as directed towards others. Such an experience is enduring in nature as it leaves the individual with a sense of contentment, builds self-confidence for a relatively longer period. This is also known as sātvika sukha.

The causes, determinants and correlates of the above two kinds of happiness match to a large extent with their western counterparts. However, in the Indian philosophy one more kind of happiness is also identified beyond these two kinds.[2]

ब्रह्मानन्दः ॥ Brahmananda (Existential/Transcendental happiness)

Brahma (or Brahman), a supreme singular entity as per Indian thought, is regarded as essential reality of every individual (across the various sampradayas) as well as the substratum of the universe. Brahmananda, is regarded as the highest form of happiness or bliss that a person can experience. It is transcendental in the sense that it transcends the limitations of compartmentalized individual existence. It is also called ‘existential’ because it is the core aspect of human existence in as much that it cannot be separated from human identity. It is subjective in nature and not dependent on any external object, situation or person. The ancient texts assure us that every individual is capable of experiencing such a state of happiness through a conscious and systematic process of Self discovery as it is the very nature of one’s being and it is intrinsic to all of us. This kind of happiness results from Self-realization which is qualitatively different from self-actualization.[2]

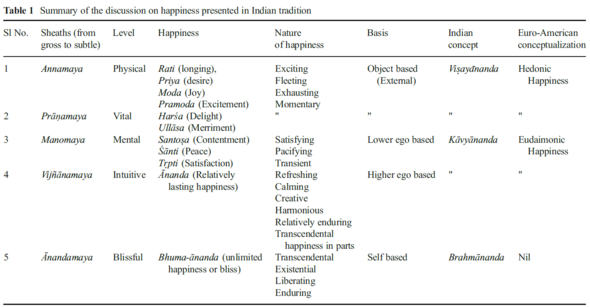

A Summary of Sukha and Ananda in Indian Traditions

The following table succinctly summarizes the various shades of sukha, and ananda and their relationship with the Panchakoshas. [2]

We can see from the above table that transcendental happiness is not defined in Western conceptualization of happiness. Hence perspectives in this area forms the core contribution of Indian thought to the world.

सुखं त्रिविधम् ॥ Three kinds of Sukha

Shrimad Bhagavadgita (18.36) defines it as ‘something which the individual rejoices having attained with effort and which also marks the absence of unhappiness.[2]

सुखं त्विदानीं त्रिविधं शृणु मे भरतर्षभ । अभ्यासाद्रमते यत्र दुःखान्तं च निगच्छति ॥ १८-३६॥ (Bhag. Gita. 18.36) sukhaṃ tvidānīṃ trividhaṃ śṛṇu me bharatarṣabha abhyāsādramate yatra duḥkhāntaṃ ca nigacchati

यत्तदग्रे विषमिव परिणामेऽमृतोपमम् । तत्सुखं सात्त्विकं प्रोक्तमात्मबुद्धिप्रसादजम् ॥ १८-३७॥ (Bhag. Gita. 18.37) yattadagre viṣamiva pariṇāme’mṛtopamam

tatsukhaṃ sāttvikaṃ proktamātmabuddhiprasādajam

विषयेन्द्रियसंयोगाद्यत्तदग्रेऽमृतोपमम् । परिणामे विषमिव तत्सुखं राजसं स्मृतम् ॥ १८-३८॥ (Bhag. Gita. 18.38) viṣayendriyasaṃyogādyattadagre’mṛtopamam pariṇāme viṣamiva tatsukhaṃ rājasaṃ smṛtam

यदग्रे चानुबन्धे च सुखं मोहनमात्मनः । निद्रालस्यप्रमादोत्थं तत्तामसमुदाहृतम् ॥ १८-३९॥ (Bhag. Gita. 18.39) yadagre cānubandhe ca sukhaṃ mohanamātmanaḥm nidrālasyapramādotthaṃ tattāmasamudāhṛtam

According to this text sukha is classified into three kinds[2]

- सात्विकम्॥Sātvika (noble): Sātvika sukha consists of such happiness which appears to be effortful (while pursuing it) but eventually tastes like nectar, i.e. very pleasant. Such happiness arises as a result of intelligent and creative efforts with a right knowledge of oneself. (Bhag. Gita. 18.37)

- राजसिकम्॥Rājasika (dynamic): Rājasika sukha is the resultant of the contact of the sense organs and the objects which appears to be pleasurable initially but unpleasant at the end, i.e. after the experience as it leaves a person with a sense of wanting. (Bhag. Gita. 18.38)

- तामसिकम्॥Tāmasika (lethargic): Tāmasika sukha, is the happiness that is delusionary in nature from beginning to the end that may arise from sleep, laziness, ignorance, illusion etc. (Bhag. Gita. 18.39)

Biological Implications of Pleasure and Happiness

Research[15] has suggested that happiness has genetic factors that account for substantial amounts of individual variation in well-being and health conditions. Despite the mounting evidence that genes play an important role in the etiology of well-being, personality, mental health, and physical illness, genetic and environmental influences on the covariance between SWB and physical health have been largely unexplored.[15] In order to help understand happiness and alleviate the suffering, neuroscientists and psychologists have started to investigate the brain states associated with happiness components and to consider the relation to well-being. While happiness is in principle difficult to define and study, psychologists have made substantial progress in mapping its empirical features, and neuroscientists have made comparable progress in investigating the functional neuroanatomy of pleasure, which contributes importantly to happiness and is central to our sense of well-being.[16]

| Happiness | Pleasure |

|---|---|

| Is not addictive | Is addictive |

| Long-term in nature | Short-term |

| Generally shared, inspires giving | Typically experienced alone |

| Makes the brain say "its enough" | Makes the brain say "I want more" |

| Serotinin driven | Dopamine driven |

An evolutionary perspective of happiness is that survival in early days was binary - a loss or gain. Humans are not designed to be happy or content. Instead, they are designed primarily to survive and reproduce, just like other creatures in the nature. A state of contentment is discouraged by nature because it would lower the guard against possible threats to survival. Happiness is a proximate goal (success) while anxiety is a distant goal (failure) to achieve adaptation. According to the evolutionary theory of emotion, human emotions exist because they serve an adaptive role. Emotions motivate people to respond quickly to stimuli in the environment, which helps improve the chances of success and survival. But, not all forms of happiness can be explained by evolution; culture, and societies play a major role. The link between pleasure and happiness, however, has a long history in psychology. While some cultures define happiness as a function of good fortune and prosperity, others define it as personal well-being and satisfaction. Unhappiness, on the other hand, has its share of evolutionary significance. It is considered evolutionarily helpful since it gives rise to emotions like jealousy, distress, and horror which, in turn, give rise to the tendency to return to happiness. Unhappiness, misery, pain etc., prevent starvation and helps in the survival process of a human being. Hence people cannot stay happy all the time.[6]

In spite of difficulties in finding special genes, several genes distributed to emotion and mood. Neuroscience studies showed that some part of brain (e.g. amygdala, hipocamp and limbic system) and neurotransmitters (e.g. dopamine, serotonin, norepinefrine and endorphin) play a role in control of happiness. A few studies pointed to the role of cortisol and adrenaline (adrenal gland) and oxytocin (pituitary gland) in controlling happiness.[17] Dopamine, is associated with reward and motivational pleasures whereas, Seratonin, is associated with contentment and happiness.

Sukha/Ananda (Happiness) Vs Svasthya (Well-being)

While a few scholars overlap happiness and wellbeing, certain characteristics draw a fine line of separation between both the terms. Happiness is a state of well-being and contentment, and is subsumed under the larger context of well-being. Well-being is, by definition, the state of being happy along with being healthy and prosperous. Happiness is an emotion whereas well-being is an evaluation/judging positivity and satisfaction with life's situations.[6]

| Happiness | Well-being |

|---|---|

| Hedonic in nature | Eudaimonic in nature |

| Emotion driven | Reason driven |

| State of mind | Evaluation of state of mind |

| Subjective | Objective |

| Informal | Formal |

| Pleasure | Meaning of life and contentment |

| Mostly mental state | Mental, physical and material elements are involved |

| May be non-evaluative | Evaluative |

Upanishadic Perspectives of Ananda and Sukha

In various Upanishads, the Taittriya, Brhdaranyaka, Mandukya, Chandogya, and Katha Upanishads, and in the Bhagavadgita, there are interesting discussion sections dealing extensively about the happiness and well-being of an individual.[2] The Vedic and Upanishadic seer and sages emphasised on realising that which is eternal (nitya) and permanent (satya), rather than going after anything that is momentary (kshanika) and that is liable to undergo decay and destruction (kshara) or impermanent (mithya). They understood Ananda, bliss, as the original condition of human beings and characterize Atman, the 'pure consciousness' or transcendental Self. It is the Ananda of sat-chit-ananda the different from the ananda of Anandamaya kosha that refers to the intrinsic condition of blissfulness. Therefore Ananda actually refers to a state of consciousness, characterised by positive feeling, which is not dependent on any object or events of external reality. Thus the experience of ananda, bliss, is a qualitatively different sense of positive state and well being from that is associated with other sheaths, koshas. Hence, a person who has an expanded state of consciousness evaluates his/her well being as ananda. The self-sense beyond anandamaya kosha is the transcendent Self, Atman, pure consciousness, which is a positive state characterized as shaanti, that is a sense of sublime peace and quietude.[18]

Tattriya Upanishad and Anandamaya Kosha

The second adhyaya in Taittriya Upanishad, is named as Brahmanandavalli. It deals with the Ananda of Sat-chit-Ananda, the attributes of Brahman. In this Upanishad, we find a detailed discussion on the nature of happiness and realizing it as the innermost core of one's being. It is also the core of human personality around which the individual Jiva, exists and functions. However, there are many layers or sheaths around this core which impede the experience of the original condition.[2]

The sheaths, Panchakoshas, that cover are five in number viz., Annamaya - physical, Prāṇamaya – the vital, Manomaya – the mental, Vijñānamaya – the intuitive, and Ānandamaya – the blissful.[18] A few interesting points about happiness (sukha) associated with these sheaths.

- Different types of emotions, positive and negative, are associated with the first three koshas (annamaya, pranamaya and mannomaya koshas). Many people feel their identities or self-sense with these three koshas, and remaining established at this level, they evaluate ill-being or well-being within this limited framework.

- At the remaining two koshas (vijnanamaya and anandamaya koshas) a person can experience only a positive state. Some persons either spontaneously or through induction from meditation, yoga and such other practices are able to move beyond the above three sheaths and narrow self-definitions. Spontaneous peak experiences, drug-induced states, and ecstatic and mystic experiences are instances of transcendence of the limitations of first three koshas.[18]

The Bhruguvalli, introduces the threefold concept of priya, moda, and pramoda in the imagery of a bird. Here, ‘priya’ is its head, ‘moda’ and ‘pramoda’ are its left and right wings respectively, ‘ānanda’ is the soul and ‘brahman’ is its base. Adi Shankaracharya, while commenting on this section, shares an interesting insight pertaining to happiness. He notes that the happiness experienced, when an object is seen or perceived with a sense of wanting it is ‘priya’,when the object is possessed, it is ‘moda’ and when enjoyed/utilized, it is ‘pramoda’.[2]

Brhdaranyaka Upanishad and Sarva Priya Bhavana

In Maharshi Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi Samvada, Maitreyi enquires about acquiring means through which she could be immortal. At the end of a detailed dialogue that ensues between them, Yajnyavalka utters the oft discussed phrase of the Upanishad

न वा अरे सर्वस्य कामाय सर्वं प्रियं भवति, आत्मनस्तु कामाय सर्वं प्रियं भवति । na vā are sarvasya kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati, ātmanastu kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati ।’(Brhd. Upan. 2.4.5)

It means, ‘for the sake of the self everything else becomes dear or desirable.’[2]

Mandukya Upanishad and Ananda in Sushupta Avastha

In the Māṇḍūkya Upanishad, the self of the individual is described using two words ‘ānandamaya’(filled with bliss) and ‘ānandabhuk’ (experiencer of bliss). However, in the previous line in the concerned section, the self is qualified as the being in the dreamless state with no desires unfulfilled.[2]

सुषुप्तस्थान एकीभूतः प्रज्ञानघन एवानन्दमयो ह्यानन्दभुक् चेतोमुखः प्राज्ञस्तृतीयः पादः ॥ ५ ॥ (Mand. Upan. 5)[19]

At the time of deep sleep (sushupti), the mind is free from those miseries of the efforts made on account of the states of the mind being involved in the subject-object relationship: therefore, it is called the "Anandamaya", that is, endowed with an abundance of bliss. But this is not the Ananda as the attribute of Brahman, because once the perceiver associates deep sleep with the Upadhi of the causal state (karana sharira). In common parlance, one, free from efforts, is called happy and enjoyer of Ananda. As the Prajna (undifferentiated consciousness) enjoys this state of deep sleep which is entirely free from all efforts, therefore it is called the "Anandabhuk’ (the experiencer of bliss). That the Prajna, in deep sleep, enjoys bliss is viewed from waking state.[20]

Chandogya Upanishad and Boundlessness

In the seventh adhyaya, in Maharshi Narada and Sanathkumara's samvada, Sanathkumara says that happiness lies in the fullness or vastness and not in a sense of limitedness.[2]

यत्रान्यत्पश्यत्यन्यच्छृणोत्यन्यद्विजानाति तदल्पं यो वै भूमा तदमृतमथ ... (Chand. Upan. 7.24)[21]

Meaning: When you are not using your organs of perception through seeing or hearing and you are free from cognizing, which are limited, that state is Bhuma which is unlimited exalted state.

The word 'bhuma', is further explained as the blissful state or expansive state. This is the state when the mind is not constricted by a stream of unending thoughts and is free of being confined.[22]

Katha Upanishad and happiness beyond worldly pleasures

In Kathopanishad, where we find the Yama Nachiketa samvada, we get rich insights in understanding the concept of happiness. Yama tries to lure Nachiketa with various forms of riches and sensual pleasures. Nachiketa emphatically states that 'wealth cannot bring him happiness' and persists in seeking the knowledge of immortality from Yama. This Upanishad treats the matter of worldly pleasures (sukha) distinctly and secondary to the higher form of happiness or Ananda, which is the knowledge of the true self.[2]

Elsewhere in this Upanishad, we find that inactivity of all the cognizing apparatus leads to an exalted state.

यदा पञ्चावतिष्ठन्ते ज्ञानानि मनसा सह । बुद्धिश्च न विचेष्टते तामाहुः परमां गतिम् ॥ १० ॥ (Kath. Upan. 2.6.10)[23]

The meaning being, when the five sense organs are not functioning when the mind and the intellect have become inactive, that is the exalted state or blissful state to attain.[22]

Several features of Happiness

Though the concepts of happiness in different countries of the world differ from each other, perhaps the quest for happiness is ubiquitous and hence universal. Happiness can be classified based on several features.[6]

- Source of happiness - Is it self driven or driven by others? The source of happiness is often conceived as coming from or due to the actions or support of other people.

- Duration of happiness - Is short-term happiness such as watching a good movie more fulfilling than long term happiness that arises due to say a spiritual reason?

- Location of happiness - Is happiness restricted to the physical body or is happiness a mental state?

- Factors of happiness - Is happiness due to external materialistic and environmental factors (marital status, education, income) or is it due to internal factors (contentment, compassion, personality, contemplation)

- Intensity of Happiness - Happiness has a peak moment (is momentary) and a non-peak state (a memory)

In certain countries enjoyment of desirable goods, entertainment and pleasure in life, in other words physical satisfaction or hedonic approach dominates. In countries like India, it is associated with spirituality and being in the protection of divine, superhuman elements such as Ishvara.

Impact of Environment on Happiness

Like well-being (Svasthya), happiness is also closely linked to environmental changes along with genetic factors.[6] Research undertaken in recent years has shown a shift in happiness from being related to pure psychology to environmental psychology, community environment and spatial governance. According to the authors of this study[24], Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is commonly used in the international community as an important indicator to measure social progress and people’s well-being. Capitalists believed that economic growth would bring us happiness, but a small, poor Buddhist country—Bhutan—has dispelled the myth with the concept of Gross National Happiness. Today, the concept of happiness has evolved from the field of psychology to all disciplines. Many researchers are exploring how environmental psychology/behavioral psychology influences residents' sense of happiness. Their results showed that factors like green area, community layout, aesthetics, transportation service and social service significantly influenced residents' sense of happiness.[24]

Impact of Personality on Happiness

Studies of personality and environmental correlates of happiness indicate that both these factors have a significant impact as happiness indicators.[6]

Traits such as helpfulness, responsibility, caring, compassion, empathy are consistently most important to be happy. Most of the times, unhappiness arises from[6]

- comparison with others, as it brings discontent

- lack of gratitude, with a focus on what is lacking instead of what has been gained

- getting attached to comfort zone, which does not motivate us to take challenges

- living with the past of future, anxious people live in the future while the depressed live in the past.

Importance of studies about happiness

Happiness matters with every individual as he tries to overcome an unhappy state of mind. It is because the survival emotions of a human being are 'unhappy', so happiness is vital for motivating us through various aspects of life. It is a life-long trait, a journey not a destination. Humans are born with a genetically determined 'set-point' for happiness as per research advances in this field. It offers us meaning and purpose of life. It helps discover new passions, generate curiosity, builds strong coping skill and emotional resources. It gives us the ability to tolerate risks and and anxiety, and keeps us healthy mentally and physically.[6]

It important to study happiness scientifically[6]

- to develop more insight for self, awareness and orientation about others, and to get rid of misconceptions about happiness.

- to get a clear perspective about ourselves, the misconceptions of life, career, notions of people, and learning about the stereotypes of people to help us develop resilience.

- to support ourselves during turbulent life experiences and manage failure effectively instead of succumbing to depression and other mental disorders.

- being happy creates happiness for others and thus we can create our happy surroundings.

Means of happiness

Social sciences in general, but neurosciences, behavioural sciences, and computational science take advantage of the theory of happiness. The following three factors have found to be major factors in experiencing happiness.[6]

- Affluence in bio-psycho-social resource that determine the quality of living and prosperity

- Autonomy in freedom to choose or in meaningful physical and mental engagements

- Appreciation for life as a whole that determines life satisfaction (subjective wellbeing)

Components of happiness

A majority of researchers now agree that happiness is most likely composed of three related components: positive affect, absence of negative affect and satisfaction with life as a whole.[25]

Most of the research done so far in the field of Psychology has focused on what the reasons are for a person to be happy or the external factors contributing to happiness. Large surveys have come up with the components of happiness factor such as:[22]

- satisfaction with life

- balanced and rational view

- quality of life

- optimism

- well-being

- self esteem

The objectives of Indian texts such as Upanishads, on the other hand, give a suggestion and a way to the seeker to look within. They encourage reaching the state of Ananda through spiritual practices or mental exercises which are within the control of the individual rather than the external forces which are not under his or her control.[22]

Misconceptions about happiness

There are common misconceptions about happiness which greatly influence a person's state of mind. A few are listed below.[6]

- Money and affluence brings about happiness

- Receiving gifts makes us happy

- Freedom of choice enhances happiness

- Longer vacations make us happier

- Negative memories prevent us from being happy.

- Pain reduces pleasure

- Getting a dream job makes us happy

Research has shown that money increases happiness to a certain extent - happiness does not increase after a salary of 75K $ per year as per some studies in the United States and that it begins to plateau after a decent salary.

Researchers found that more than receiving a gift, purchasing a gift increases happiness. This correlates with why the ancient Indian seers stressed on dana or the giving tradition. Biologists and neurologists found a neural link, that gets activated in creating happiness for others.[6]

It is also known from studies that "some" choice and not "too many choices," enhance happiness. Research by Barry Schwatz has shown that too many choices create a burden on the cognitive abilities and cripple decision making capabilities.

Regarding vacations, it has been found that a long vacation does not make one happier as memories mix together instead of momentary happiness.

Forgiveness is an important trait that helps people overcome negative memories; studies show that forgiving people have better fitness and quality of life. Research also shows that forgiving others for mis-deeds reduces long-term stress and has a great unburdening effect.

As for pain reducing pleasure, research has shown that relief from pain helps us recognize pleasure, and forms social bonds. While pain is inevitable suffering is optional.

Research points to the fact that everyone becomes habituated with novelty, excitement and learning in a new job, and soon one becomes unhappy.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Happiness and well-being in Indian tradition," Psychological Studies 51, no. 2-3, (2006): 105-112.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Banavathy, V.K., Choudry, A. Understanding Happiness: A Vedantic Perspective. Psychol Stud 59, 141–152 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-013-0230-x

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Choudry, A, and Banavathy, V.K. Understanding Happiness: the Concept of sukha as 'Excellent Space'. Psychol Stud 60, 356–367 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-015-0319-5

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shabdakalpadhruma (See आनन्दः)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Term Ananda in Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary by V. S. Apte.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 The Science of Happiness and Wellbeing. NPTEL Course

- ↑ Salagame, Kiran Kumar, "Meaning and Well-being: Indian Perspectives," Journal of Constructivist Psychology. (2016) 30:1, 63-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2015.1119087

- ↑ Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 305-306

- ↑ Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 212

- ↑ Paranjpe, Anand. C. and Ramakrishna Rao, K. (2016) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 64-65

- ↑ Panchadasi (Prakarana 11)

- ↑ Srinivasa Rau, M. Panchadasi of Vidyaranya, With English translation, Explanatory notes and Summary of each chapter, Sriranga: Sri Vani Vilas Press (1912) 519

- ↑ Srinivasa Rau, M. Panchadasi of Vidyaranya, With English translation, Explanatory notes and Summary of each chapter, Sriranga: Sri Vani Vilas Press (1912) 593-594

- ↑ Srinivasa Rau, M. Panchadasi of Vidyaranya, With English translation, Explanatory notes and Summary of each chapter, Sriranga: Sri Vani Vilas Press (1912) 616-617

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Røysamb, Espen & Tambs, Kristian & Reichborn-Kjennerud, Ted & Neale, Michael & Harris, Jennifer. (2004). Happiness and Health: Environmental and Genetic Contributions to the Relationship Between Subjective Well-Being, Perceived Health, and Somatic Illness. Journal of personality and social psychology. 85. 1136-46. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1136.

- ↑ Kringelbach, M. L., & Berridge, K. C. (2010). The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure. Social research, 77(2), 659–678.

- ↑ Dfarhud, D., Malmir, M., & Khanahmadi, M. (2014). Happiness & Health: The Biological Factors- Systematic Review Article. Iranian journal of public health, 43(11), 1468–1477.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Salagame. K. Kiran Kumar, An Indian Conception of Well Being. In Henry, J. (Ed) European Positive Psychology Proceedings (2003)

- ↑ Mandukya Upanishad

- ↑ Swami Nikhilananda, trans, The Mandukyopanishad with Gaudapada's Karika and Sankara's Commentary, Mysore: Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama, (1949) 23-26

- ↑ Chandogya Upanishad (Adhyaya 7)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Hemachand, Lata. The Concept of Happiness in the Upanishads and its Relevance to Therapy, Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2021, 48, no. 2, 123-130

- ↑ Katha Upanishad (Adhyaya 3 Valli 3)

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Chiu-lin Chen and Heng Zhang, Do You Live Happily? Exploring the Impact of Physical Environment on Residents’ Sense of Happiness, 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 112 012012. DOI 10.1088/1755-1315/112/1/012012

- ↑ Lu, Luo. Personal or Environmental Causes of Happiness: A Longitudinal Analysis, The Journal of Social Psychology, (1999), 139 (1), 79-90