Difference between revisions of "Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi, Chikmanguluru, Karnataka"

m |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The Veera Narayana Temple, is a temple dedicated to Veera Narayana, a form of Lord Vishnu, in the village of Belavadi, Chikamagalur district, Karnataka. The temple was built in the 12<sup>th</sup> century CE by the Hindu dynasty of the Hoysalas, based at Halebidu. They also built the famous temples at Belur and Halebidu. | + | The Veera Narayana Temple, is a temple dedicated to Veera Narayana, a form of Lord Vishnu, in the village of Belavadi, Chikamagalur district, Karnataka. The temple was built in the 12<sup>th</sup> century CE by the Hindu dynasty of the Hoysalas, based at Halebidu. They also built the famous temples at Belur and Halebidu. [[File:Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi, Chikamagaluru, Karnataka.jpg|thumb|''Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi, Chikamagaluru, Karnataka'']] |

| − | |||

== Sthala Purana == | == Sthala Purana == | ||

| − | |||

Belavadi is called the ‘Ek Chakra Nagara’ because it is believed that Bhima, one of the five Pandavas, killed the demon Bakasura here. This story from ''The Mahabharata'' is famous about many places. Belavadi is one of those places. | Belavadi is called the ‘Ek Chakra Nagara’ because it is believed that Bhima, one of the five Pandavas, killed the demon Bakasura here. This story from ''The Mahabharata'' is famous about many places. Belavadi is one of those places. | ||

Revision as of 11:47, 19 March 2019

The Veera Narayana Temple, is a temple dedicated to Veera Narayana, a form of Lord Vishnu, in the village of Belavadi, Chikamagalur district, Karnataka. The temple was built in the 12th century CE by the Hindu dynasty of the Hoysalas, based at Halebidu. They also built the famous temples at Belur and Halebidu.

Sthala Purana

Belavadi is called the ‘Ek Chakra Nagara’ because it is believed that Bhima, one of the five Pandavas, killed the demon Bakasura here. This story from The Mahabharata is famous about many places. Belavadi is one of those places.

Belavadi – The Ek Chakra Nagara

The Mahabharata tells the story of a demon Bakasura, who is killed by Bhima. Bakasura was a ferocious demon who lived near the town called Ekchakra Nagara. He was so ferocious that not even the king was capable of hurting, let alone killing him. He did what he wanted. Threatening to lay waste to the entire town, he demanded daily supplies, putting a great strain on the town. But this was not the entire story. He used to eat the man who delivered the supplies too, alive. Everyone was afraid of him and wanted to get rid of him as the town was getting depopulated.

It was the time when the Pandavas were living in exile in the forest. During their wanderings, they arrived and started living at Ek Chakra Nagara. The people were very hospitable and the Pandavas were happy until one day Kunti heard the cries of her host, as they were staying with a Brahmin family. The family was arguing over whose turn it was to sacrifice his life. Everyone wanted to sacrifice themselves. When Kunti asked about the reason, they told him about Bakasura. Apparently, it was their family’s turn to deliver supplies to Bakasura and get eaten by him.

Kunti came up with a plan. She told the Brahmin to send Bhima, her son, instead of his son. Brahmin did not agree at first, but Kunti said that her son is very strong and moreover she had five of them and even if she lost one she would have the consolation of having four others. She sent Bhima to kill Bakasura.

Upon arriving at Bakasura’s cave, Bhima ate all the food that was meant for Bakasura, angering him. Bakasura came at Bhima and a great battle ensued in which Bhima killed the demon[1]. The villagers became happy but the Pandavas had to leave as they were in a secret exile and their identity should not have been discovered.

There are many places which have the claim to be the Ekchakra Nagara. Rampurhat and Pandevswar near Durgapur in Burdwan, West Bengal are two candidates. Pratapgarh in Uttar Pradesh is another candidate. Erandol in Jalgaon, Maharashtra is also claimed to be the Ekchakra Nagara. Finally, the town of Belavadi, in Chikamagalur district of Karnataka, which is the subject of this study is also claimed to be the Ek Chakra Nagara.

Recreation of Sacred Space

In India, in order to spread the reach of Sanatana Dharma, over the course of its evolution the sacred geography was replicated over the length and breadth of its geographical realm. Madurai was modelled on Mathura in Uttar Pradesh. Ayutthaya in Thailand was modelled on Ayodhya. Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu was modelled on the name of Kashi. River Mekong is named after ‘Maa Ganga’.

Sanjeev Sanyal writes in Land of the Seven Rivers: A Brief History of India's Geography that Indian civilization started from the great land of Sapta-Sindhu, what would today constitute as the Ganga-Yamuna doab and the land comprising western India, along with the dry bed of Saraswati river. It then spread to the Deccan, south India and even what is now South-east Asia. In order to spread Sanatana Dharma, the sacred geography of the Sapta-Sindhu area was replicated everywhere the Sanatana influence was spread. Not everyone could travel and take part of the holy river Ganga; hence many rivers were declared to be as holy as the Ganga. The same was true about the holy places.

This is the reason that same legends are famous about many places. In the eyes of western scholarship, only one place has the true claim and the others are just usurpers. But in Hindu philosophy, the spirituality of a place is more important than its historicity. Many places can be similarly ‘authentic’ in their legends.

Celebrations

The town of Belavadi is widely believed in Karnataka as the Ekchakra Nagara. The townspeople of Belavadi celebrate the killing of Bakasura with great fanfare every year, in the month of April. A procession is taken out in which the Utsava Murti is taken on a Rath Yatra to a small temple outside the village, where Bakasura is believed to have been killed. The procession also consists of a bullock cart full of rice and other foods like jaggery to be offered to the deity. The procession goes through the whole town of Belavadi and then arriving at the temple beneath the hill, the village deity is worshipped. Prasadam is distributed among the devotees and everyone comes back home. This festival has a long history and the local people maintain that it has been going on for at least as long as 150 years.

The Age of the temple

An inscription found at the Veera Narayan temple mentions the temple land being donated by the king for the construction for the temple and the year of the donation is denoted as 1117 CE. However, according to a scholarly estimation the temple was built in 1200 CE. Gerard Foekema has arrived upon this estimate by comparing the development of the Hoysala architectural style and placing it in history.

The priest Prashant S. Bharadwaj says that what is mentioned in the 1117 CE inscription is the donation of the land. The tradition in ancient India was that a temple land was donated after the temple had been entirely built on the land and hence since the year mentioned of donating the land is 1117 CE then the temple must have been built even earlier than that.

The extent of the land donated to the temple is calculated by the needs of the institution of the temple. For example, the temple needs rice for offering to the deity, flowers for the decoration and many other such products. For growing them, land is needed. An estimate is made about how much land would be needed to cover all the needs of the temple and the estimated land is donated to the temple. This assessment of the land to be donated can only be made after the temple has been completely built and that is why first the temple is constructed and only then the land upon which it is built is donated.

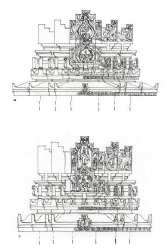

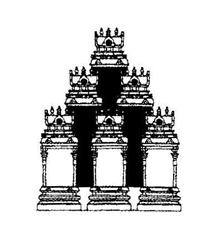

The architecture of the temple also hints that the temple is much older than is suggested by the scholars. The temple was built in primarily two stages. The temple at Belavadi is a trikuta temple with three shrines. The main shrine is dedicated to Lord VeerNarayan. The walls of this shrine are severely plain compared to the Hoysala temples dating to the year 1200 CE.

They are also in sharp contrast to the other two later subsidiary shrines of the temples which have exquisitely decorated walls in the style of the later Hoysala architecture. The two lateral shrines were built much later, during the reign of Veera Ballala II. This also hints that the original shrine is much older than 1200 CE and may belong to early 12th century.

The earliest Hoysala temple at DoddaGaddavalli has many similarities to this Veera Narayan shrine temple at Belavadi. Just like DoddaGaddavalli temple is severely plain from the outside, so is the primary shrine of Belavadi. The DoddaGaddavalli temple dates back to 1114 CE, indicating that the age mentioned in the inscription may be true.

This temple was built under the reign of two kings in two periods. The two parts of the temple with their characteristic evolution can easily be seen.

The Temple Escaped Islamic Destruction

The age when the Hoysalas were building great temples was also the age of Islamic iconoclasm in India. The iconoclastic zeal of the invading Islamic kings of the Delhi Sultanate had broken upon south India. Malik Kafur broke upon Karnataka in 1311 CE and laid siege to Halebidu ruled by the Hoysalas. The Hoysalas agreed to pay tribute to the Islamic vandal. Even then Kafur managed to destroy the great Hoysaleswara temple and many other temples in the region. The head priest of Belavadi claims that Kafur had come up to nearby Tarikere. But Belavadi, due to its location in a quaint mountainous village, escaped the Islamic destruction.

The Hoysala dynasty and Architecture

The prevalent custom among the scholars of Hindu architecture is to name the architectural styles of geographical regions based upon the names of the dynasties of kings who ruled there. The custom derives from the fact that in Hindu architecture, the artist is not as important as the piece of architecture. The architects seldom attached their names with their pieces of work. However, the great temples that were constructed during the golden era of Hindu temple building also became famous on the names of the king who commissioned the projects.

Building a temple was a huge project. Sometimes it took years and even decades. The Ramappa temple, Warangal, Telangana is said to have taken eighty years to complete. Hindu society held temples in great esteem and donated money so that great temples could be built. However, the planning, co-ordination and sustained protection that such a project needed could only be provided by a great king.

That is why many of these temples became famous on the names of the rulers who commissioned them. The tradition still continues and the scholars of Hindu temple architecture continue to classify regional varieties of temples on the names of the dynasties that built them.

The Veera Narayana temple was built by the Hoysala dynasty. If the earlier date of the temple is taken to be true then it was built during the reign of Vishnuvardhan king of the Hoysala dynasty in 1117 CE.

The Hoysala were a minor dynasty of kings who came to rule central and southern Karnataka during the 12th and 13th centuries. Though they had been ruling before, their political fortunes rose after the fall of the great Chalukyas of Kalyani, also known as the Later Chalukyas. It is then that they expanded in size. Many small dynasties rose after the Chalukyas to claim or reclaim many regions. The Hoysala were one of them.

They ruled the areas which roughly correspond to what is now the district of Hassan, some parts of Chikamagalur, Shivamoga, Mandya, Coorg, Chitradurga etc. They were sandwiched between the two great powers: the Chalukyas in the north and the Cholas of Thanjavur in the south. Initially they were a small kingdom straddling the mountains of the Western Ghats. In the 11th century they remained the vassals of the Chalukyas, gradually enlarging their territory.

Only in the 12th century did they rise and become powerful when Hoysala king Viraballala defeated the Chalukyas of Kalyani and put an end to the great empire. For about 200 years they reigned supreme and became what the Cholas and the Pandyas were in Tamil Nadu, and what the Chalukyas were in Karnataka. They continued to wax and wane in power until the invaders and iconoclasts of the Delhi Sultanate arrived in south India.

The Hoysalas sometimes chose to fight them, and sometimes to pay tribute to them, but when the Vijayanagar Empire rose in 1329 under Harihar and Bukka, they submitted themselves willingly to the Vijaynagar Empire so that a united front against the Islamic invaders could be created in south India. In 1342, Ballala III died and the Hoysala Empire was fully incorporated in the successor empire, the Great Vijaynagar Empire.

The Hoysalas, as mentioned, were great patrons of art. The vibrant temple tradition that was flourishing in south India in those times sustained guilds of architects, sculptors and other artisans who worked as a unit.

The kings just commissioned the project. The temples were constructed by professional and specialized guilds. These guilds easily travelled from one kingdom to another and worked for anyone who commissioned the project. That is why knowledge of architecture and sculpture was easily transferred from one dynasty to another. The art of temple building in Karnataka in what is called as the Vesara style was well developed during the time of the Chalukyas of Kalyani. The Hoysala merely continued and developed it. The major innovation during their time was the exquisite embellishing of the temple exteriors by extremely fine sculpture.

They built their beautiful temples in soapstone, variously called as potstone too. The stone is dark gray or black in color and is very soft when quarried. However, within a decade it becomes very hard on exposure to wind and rain. This peculiar quality makes it perfect for deep, miniature and exquisite sculpting. That is why the Hoysala temples are beautifully embellished with exquisite sculpture in high or low relief, or freely sculpted sculptures fitted later into the temples.

The Hoysala Temple

A Hoysala temple has many parts, interconnected to each other. Thus, unlike the Tamil Nadu temples, a Hoysala temple is a complete coherent whole; a connected building which does not break in continuity.

The simplest form of Hoysala building consists of just the shrine of the primary deity and a mandapam attached to it, which can either be closed or open. In some bigger temples both open and closed halls are to be found. As discussed above, the sanctum is for the deity and the mandapam is for the devotees to gather and have darshan. In most temples, between the mandapam and the garbha-griha, there is antarala, or the vestibule. In some bigger temples there are entrance porches, or mukha mandapams before the mandapams at the entrance of the temple. Thus there are five primary constituent parts of a Hoysala temple: garbha-griha, antarala, mandapam (closed), mandapam (open), mukha mandapam (porch).

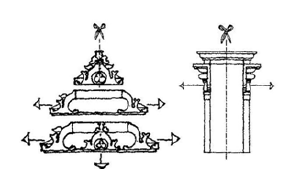

The vimana of the Hoysala temple is extremely articulated, artistic and complex in nature and is what attracts the tourists most of all. Gerard Foekema explains:

“Its inside forms a strong contrast to its outside: the inside is simply square in plan with plain walls, hence the name cella, the outside is complicated in plan and is profusely decorated. The outside plan is a star, a staggered square or a combination of star and square, and consequently the walls show many projections and recesses.”[2]

The antarala too is plain from the inside and has just the space for the priest to officiate between the devotee and the deity. Its walls are plain or barely decorated from the inside. The mandapams are divided into bays. Their ceilings are decorted with padma motifs, oral patterns and other decorative motifs. On the outside the walls are profusely decorated, but their decoration is integrated with that of the outer walls of the garbha-griha and is inconspicuous. It also has a roof in the form of a nose like structure protruding from the vimanas. It is called shukanasika.

In most Hoysala temples, the closed mandapam has either no windows, or perforated windows which let in some light. It has thick walls. It is a large hall and hence there are four pillars to support the roof. Both outside and inside of the mandapam are decorated. The pillars are the famous lathe-turned and the ceilings of the bays of the mandapam are exquisitely decorated. It is large but smaller than the open mandapam.

The open mandapam has an intricate plan. It is a staggered square of many sizes and variations. The number of pillars and bays vary here and the open mandapam of Veera Narayan temple Belavadi has one of the largest open mandapams of any Hoysala temple.

As it is open it has only parapet walls on which many pillars rest. The inside of the parapet has kakshasana (seating bench). The mukha mandapam is very small, just an opening with a roof and two pillars supporting it.

Hoysala Sculpture

In the Hindu temple, sculpture is inextricably enmeshed with architecture to the point where the boundary between them becomes unrecognizable. This is another feature which distinguishes the Hindu temple from other sacred architectures in the world. In the Hoysala architecture this feature becomes even more exaggerated. As Gerard Foekema says, in Karnataka, mainly in Kalyani Chalukya and Hoysala temples, architecture is decorated with architecture. These architectural parts are both functional and decorative. Since most of these parts are constructed by chiseling hence they are technically sculpture but play the function of architecture as well.

Beginning from the top, the Hoysala temple has the quintessential kalasha, containing the temple seed. It was built in stone, but in most temples it was lost during Islamic invasions, but some like temples at Mosale have their kalasha intact. The Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi also has the kalashas intact in all three of its shrines. The temples that have lost their kalasha have replaced it with a metal one.

Below the kalasha there is the domed roof, which is actually a sculpted stone and given the shape of the roof. It is square if the plan of the garbha-griha and shikhara is square and star if the plan is that of a star. “Below this giant topping roof, the tower consists of many more domed roofs with square plan, all of them much smaller, and also crowned by kalasas. They are mixed with other small roofs of different shapes, most of them finely decorated. The top of the wall of a closed hall also shows this kind of decorated miniature roofs, but only one single row of them, and also above the heavy eaves of open halls and porches one row of them can be found. The tower of the shrine mostly consists of three or four of this kind of rows, the top of the nose mostly of two or three of them.”[3]

The Vesara style has evolved basically from the south Indian Dravida style with some Nagara embellishment. Hence, essentially it is a Dravida style which later evolved into a separate branch. This is why the Dravida feature of the vimana having many talas are also present in the Vesara styles. The rows of decorated miniature roofs that Foekema talks about in the above excerpt are actually these talas which are so decorated and so deeply enmeshed into each other that they look like a single structure.

Below the vimana there is the hanging eave which is often half a metre long and is very heavy. It provides the shade to the sculpture on the walls. Below this eave two different architectural idioms are usually found. They are called the Old Hoysala type and the New Hoysala type. The Old Hoysala is very similar to the Chalukya style. The New Hoysala style features many innovations and it is this style which gave the Hoysala temples their characteristic touch. Foekema explains the differences between the two types:

“In the Old kind of temples, the wall-images are placed below the decorative towers, and below the wall-images the base of the wall consists of a set of 5 different horizontal mouldings, one of them a row of blocks. In the New kind of temples there is a second eave running around the temple, about one meter below the first one; the decorative towers are placed between the two eaves, and the wall-images below the lower one. The base of the wall consists of a set of 6 equal rectangular mouldings, each of them of the same width.”[4] The wall images that form a continuous row all around the walls of the garbha-griha and antarala are one of the most beautiful features of the Hoysala temple. They are exquisitely sculpted and are often capped by an overhanging tree or a creeper. The images on the rathas, or the projections, are of major deities, often the different forms of the primary deity in the shrine. This image is flanked by chanvara bearers or attendants. Lesser divinities occupy other less important projections.

Below this is the temple base. It is the temple base and the second eave which differentiate the Old and the New styles in the Hoysala architecture. The base consists of five mouldings, each of a peculiar shape. These mouldings of the base are an integral part of the Hindu temple and almost invariably exist in all styles and regional variation. Many of them are decorated, but only minimally.

In the New kind of Hoysala architecture, these five traditional mouldings are replaces with six bands of sculptured rows. They are called friezes. From top to bottom they show hansa, makara, stories from epics, vegetal scroll, horses and the elephants. There are a few exceptions to this like the Halebidu Hoysaleshwar temple which has eight friezes instead of six.

The Hoysala temples are mainly dedicated to either a form of Shiva or that of Vishnu. In temples with more than one shrine some individual shrines are dedicated to Surya or Lakshmi. Vaishnava trikutas always have all three shrines dedicated to a form of Vishnu, while Shaiva trikutas have one shrine dedicated to Shiva while two others to Vishnu and Surya. Images of other gods and goddesses like Surya, Brahma, Durga, Ganesha etc. are also found in the temples but entire temples are seldom dedicated to them.

While Shiva is mostly worshipped in the iconic form of a Shiva Lingam, Vishnu is always worshipped in the form of a human image. He is shown in his various avatars, numbering ten. He is also showed in deep sleep on Shesha Naga, a coiled serpent as Shesh Shayi Vishnu. He is also shown with his consort Lakshmi as Lakshmi-Narasimha or Lakshmi-Narayana. More importantly, in the Hoysala temples, Vishnu is variously depicted as holding four major ayudhas: shankha, chakra, gada, padma. He wields them in four hands. Different permutations of these four ayudhas in four hands make 24 representations of Vishnu, each with a different name and attribute, as described in the table below. The list tallies to the list given in the Patala-Khanda of the Padma Purana:

| NAME OF VISHNU | UPPER RIGHT HAND | UPPER LEFT HAND | LOWER LEFT HAND | LOWER RIGHT HAND | |

| 1. | Keshava | Shankha | Chakra | Gada | Padma |

| 2. | Narayana | Padma | Gada | Chakra | Shankha |

| 3. | Madhava | Chakra | Shankha | Padma | Gada |

| 4. | Govinda | Gada | Padma | Sankha | Chakra |

| 5. | Vishnu | Padma | Sankha | Chakra | Gada |

| 6. | Madhusudana | Sankha | Padma | Gada | Chakra |

| 7. | Trivikrama | Gada | Chakra | Sankha | Padma |

| 8. | Vamana | Chakra | Gada | Padma | Sankha |

| 9. | Sridhara | Chakra | Padma | Shankha | Gada |

| 10. | Hrishikesha | Chakra | Gada | Shankha | Padma |

| 11. | Padmanabha | Padma | Sankha | Gada | Chakra |

| 12. | Damodara | Sankha | Gada | Chakra | Padma |

| 13. | Samkarshana | Sankha | Padma | Chakra | Gada |

| 14. | Vasudeva | Chakra | Sankha | Gada | Padma |

| 15. | Pradyumn | Sankha | Chakra | Gada | Padma |

| 16. | Aniruddha | Gada | Shankha | Padma | Chakra |

| 17. | Purushottama | Padma | Shankha | Gada | Chakra |

| 18. | Adhokshaja | Gada | Shankha | Chakra | Padma |

| 19. | Narasimha | Padma | Gada | Shankha | Chakra |

| 20. | Achyuta | Padma | Chakra | Shankha | Gada |

| 21. | Janardana | Padma | Chakra | Shankha | Gada |

| 22. | Upendra | Shankha | Gada | Chakra | Padma |

| 23. | Hari | Shankha | Chakra | Padma | Gada |

| 24. | Sri Krishna | Gada | Padma | Chakra | Shankha |

These representations are found all over the Hoysala temples, including the Veera Narayan temple, Belavadi. The Chenna Keshav temple at Belur has the representations of all twenty-four forms of Chaturvimshati Murti, the 24 forms of Vishnu.

Description of the temple deity

Veera Narayana

The temple deity of the Veera Narayana temple, in the central shrine is a form of Vishnu, known as Veera Narayana. The image is of 8 feet (2.4 m). The iconography of Veera Narayana is different from the 24 images of Vishnu in Chartuvimshati Murti. Veera Narayana, standing upon the Garuda Peetha, (the seat of his vehicle, the eagle Garuda) in the temple at Belavadi holds:

- Upper right hand – Padma (Lotus)

- Upper left hand – Gada (Mace)

- Lower right hand – Vyaghra Hasta

- Lower left hand – Veera Mudra

Instead of shankha and chakra, the usual ayudhas of Vishnu along with gada and padma, Veera Narayana has Vyaghra Hasta and Veera Mudra, which differentiates this form of Vishnu from others.

In Vishnu Purana there is a story where Vishnu killed Shakasura. For killing the demon, he used Shankha to fight the demon, Chakra to kill him. It is after killing him that he stood in the Veera Narayana pose, displaying righteous anger and dharmic justice. The pose exudes righteous chivalry and valour. Vyaghra means tiger and thus Vyaghra hasta means tiger hand, someone who is quick and strong like a tiger. Veera Mudra is a pose in which the deity holds a small weapon in his hand. Unlike other representations of Vishnu, this one shows him in a warlike pose. That is why this form is called Veera Narayana.

The prabhavali that decorates Veera Narayana in the background has a makara head exuding the prabhavali which is decorated with the Dashavatar of Vishnu – Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parashurama, Rama, Balarama, Buddha and Kalki. It shows Balarama instead of Krishna because Veera Narayana himself is identified with Krishna. On either side of Veera Narayana there is Shridevi and Bhoodevi, the two consorts of Vishnu. The deity faces east and the leveling of the ground in front of it is marvelous. For 270 feet the ground is extremely leveled. The horizon is visible from the ground, sitting at the gates of the garbha-griha. On 23rd March, the sunlight comes through the seven doors from the entrance and falls at the feet of the idol.

Venu-Gopala

The two lateral shrines which the devotee finds first at entering the temple are dedicated to Venu-Gopala, a form of Krishna and Yoga Narasimha. The Venu-Gopala shrine faces north. The image of the deity is that of Venu-Gopala. It is a form of Krishna playing flute in extreme bliss, in control of all the senses, personified in the form of Gopis. He is playing flute, standing in tribhanga, under the Kalpavriksha tree. The image has to be extremely beautiful as ordained in the Agamas, and the sculptor of this image at Belavadi has taken the injunction of the Agamas very seriously. This is officially certified by the ASI as the most beautiful representation of Venu-Gopala, anywhere in India. The form of Venu-Gopala is well described in Agamas and Puranas. In the words of T. A. Gopinatha Rao:

“Venu-Gopala is another variety of the Krishna image, in which he is conceived to be delighting with his enchanting music the hearts of the cowherds, the cowherdesses, and the cows who are his companions. In the case of these images, the rapture of music has to be clearly depicted on the face; and they are in consequence generally so very pretty as to attract attention wherever they may be. Venu-Gopala is generally surrounded by cowherds and cowherdesses. This image of Krishna is made to stand erect with the left leg resting on the floor; and the right leg is thrown across behind or in front of the left leg so as to touch the ground with the toes. The flue is held in both the hands, and one end of it is applied to the mouth. It is said that the complexion of such images of Krishna should be dark in hue so as to resemble the rain-cloud in appearance. The head should be ornamented with a bunch of peacock’s features. There should be three bends in the body.”[5] Keeping with the injunction of the Agamas and the other Shastras, the image is in tribhanga pose and as the Hoysala sculpted and built architecture in black stone the images were always made in deep black stone. On either side of Venugopala there are to be seen four sages (brahmarishis), two on each side. Rukmini and Satyabhama, the two consorts of Krishna are also present on the either side. Added to this, there are gopis and cows. Three gopis are listening to the flute of Venu-Gopala in enraptured attention, and one is so engrossed that she is not even aware of her vyjanthika (dupatta). The cow is also enraptured and is completely oblivious of her calf who is feeding on her milk. She is also listening to Krishna playing flute. The cowherds are also dancing in rapture, the bliss of self-realization engulfing them, the bliss which is symbolized by the music of the flute of Krishna.

Yoga Narasimha

The shrine in front of the Venu-Gopala shrine, and which is facing north is the shrine of Yoga Narasimha. Narasimha is usually described in four forms:

- Stambha Narasimha – When the Lord comes out of the pillar, full of anger against the demon. This is depicted realistically as the Lord coming out of the pillar which is rent asunder by his power.

- Ugra Narasimha – The Lord is depicted in this angry pose as sitting down on the sill, at dusk, tearing apart the demon Hiranyakashyapa with the claws of his hands.

- Lakshmi Narasimha – After killing the demon, Narasimha is angry and to pacify him, Lakshmi is invited to sit on his lap. This pose is depicted as the still angry Narasimha with Lakshmi sitting on his lap.

- Yoga Narasimha – The Lord has been pacified and in order to quieten his anger he sits in the Yogic pose to meditate.

The temple shrine at Belavadi depicts the Yoga Narasimha form of Narasimha. He is sitting in deep meditation with the Yoga belt tied down his knees. He is sitting erect. The upper hands are holding shankha and chakra and the lower hands are resting on the knees in meditative posture. Shridevi and Bhoodevi are on either side of the deity. The Yoga belt is decorated. The prabhavali once again depicts the Dashavatara.

In the prabhavali of Yoga-Narasimha, instead of the kirtimukha at center, there is padma. This peculiarity is due to the reason that kirtimukha is a symbol of shakti (energy) and since Narasimha is so full of energy he needs to calm down. That is why a symbol of calm and serenity padma is portrayed instead of the symbol of shakti in order to calm the great god down and balance his rajasika qualities with sattvik ones. It is for balancing shakti and shanti.

The eyes of the gods are applied with a white powder called Sri Churna. It makes them prominent. During every Abhishekam, this powder is washed away and it has to be applied again.

The priest blesses the devotee by putting the Shadgopura on his head. A Shadgopura is a miniature gopuram with the feet of the god made on it. It symbolizes the feet of the god, as everyone cannot touch the feet by coming inside the garbha-griha; the shadgopura is available for every devotee. In this arrangement, the devotee does not have to go inside the garbha-griha but the feet of the deity come outside to bless the devotee. The image at Belavadi is not in agreement with the injunctions in Silparatna which requires one leg folded and one leg resting on the ground with the Yogapatta going across the leg and above the waist. But there are examples and other injunctions which tally to the depiction of Narasimha in Belavadi. According to Margaret Stutley, Yoga Narasimha should be depicted in either of the poses:

“A yogic aspect of Narasimha, the man-lion incarnation (avatara) of Visnu. He is portrayed squatting (utkutikasana) with a band to hold one or both knees in position (yogapatta).”[6]

Utsava Murtis

The Utsava Murtis of all three deities are also present in the temple. They are made of Panch Dhatus (gold, silver, brass, copper and lead) and it is these images which are taken out for procession on various festivals. The temple does not have any permanent temple ratha now. Every year they make a temporary palki (ratha) and use it for the purpose of the festival.

Other temples of Veera Narayana by the Hoysala dynasty

There are five famous temples dedicated to Veera Narayana which were built by the Hoysalas in Karnataka, known by different names. They are:

- Melukote – Chelva Narayana

- Talakadu – Keerti Narayana

- Kiretondunoru, near Melukote – Nambi Narayana

- Veera Narayana – Gadag

- Gundulpeta – Vijay Narayana

Description of the temple

Material

The Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi is built in soapstone like all other Hoysala temples. Soapstone is of three kinds: whitish, greenish and blackish. Most of the more famous Hoysala temples like the Chenna Keshava temple at Belur and the Hoysaleswara temple at Halebidu are built in primarily black and greenish soapstone. But the Veera Narayana temple is built in whitish soapstone. The whitish soapstone is of an inferior quality than the green or black soapstone. The fact that Belavadi temple is built in whitish soapstone, has given it a completely different look. Its hue is pinkish white with a tinge or orange and black at some places.

After weathering of at least 800 years the effects are to be seen. While the sculpture at Belur and Halebidu is almost intact after all these years, the sculpture at Belavadi has deteriorated with time.

The images of the deities are built in black soapstone. The priest claims that they are built in Shaligrama.

The Plan

The Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi is a trikuta temple, meaning it has three shrines dedicated to Veera Narayana, Venu-Gopala and Yoga-Narasimha respectively. The temple was built in two steps. First an ekakuta, temple with one garbha-griha was built. A closed hall and an open hall were attached to it. This was built in the earlier age of Hoysala architecture and the walls of the shrine from the outside are completely plain, similar to earliest of Hoysala architecture.

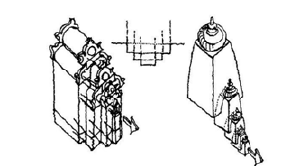

In a later age, the temple was converted to trikuta, when two lateral shrines were added to it, taking the number of shrines to three. First an exceptionally large mandapam of staggered square shape was added to the open mandapam of the earlier shrine and on the two lateral sides of this mandapam, facing north and south, the two shrines were built. Of the three vimanas, the Veera Narayan is the smallest, Venugopal bigger than that and that of Narasimha the highest of all. Although the difference is imperceptible from a distance.

The effect is spectacular. This is the only trikuta Hoysala temple in which the three shrines are not attached to each other but are separated by three mandapams. Gerard Foekema calls this temple having “the most majestic temple front in all Hoysala architecture”.[7] The larger hall (mandapam) is so majestic that it is seldom matched in Hoysala architecture. Gerard Foekema gushes forth about it:

“This hall is of a common design but of an uncommon size, 9 ankanas deep instead of 5 or 7, and consequently it has a total surface of 61 ankanas. Two of these, however, are used to provide the lateral vimanas with a sukanasi, so the actual number of ankanas of the giant hall is 59.”[8] An ankana is a bay.

The total length of the temple is 65 m and the width of the most impressive façade with two lateral shrines is 35 m. The oldest shrine which houses the Veera Narayana image is a complete temple in itself with a garbha-griha, an antarala or shukanasika, a closed hall (mandapam) with 9 bays and an open hall with 13 bays.

To describe the vimana of a Hindu temple certain terminology is necessary. The walls of the garbha-griha, antarala and mandapam support vimanas of different kinds. These vimanas are built of aediculae. Between the vimana and the walls a horizontal section of the parapet is decorated with elements which are also present in the vimana.

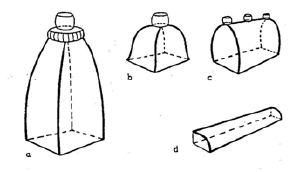

This decoration, above the parapet, generally consists of elements such as kuta, shala, panjara and a chain of them called a hara. These aediculae are nothing but miniature forms of various kinds of vimanas. Kuta is the square domed vimana aedicule is called kuta and is generally found at the corner of the vimana. Shala is the barrel-roofed and rectangular roof of the vimana of a gopuram in south India. Its miniature form in aedicule is called shala. Finally, panjara is the cross-section of a shala vimana, generally which is visible in the vimanas roofs of gopurams.

These are the basic aediculae which make up the vimana, but there are some other techniques with which the design of the vimana is made even more complex. Most common of them are staggering and splitting. Staggering is defined by Adam Hardy as:

“Staggering, or progressive stepping out, suggests expansion in stages, a serial emanation. Closely bunched offsets can also create the impression of vibration (spanda) as if with inner energy. A staggered sequence of forms, embedded one within another, can be entirely at one level (in which case the elements slide out like an unfolding telescope) or step down as they step out.”

Splitting is another technique in which an aedicule or architectural motif such as a panjara, or a stambha is split into half with the intervening space either remaining empty or containing a niche figure.

Bursting of Boundaries - When a form which is projecting and enshrined within a frame, actually bursts over in its expansion, and overstepping its boundaries appears to be leaving the confines of its frame. It suggests a greater sense of movement and expansion.

Progressive multiplication - Starting from top to bottom, a whole aedicule is multiplied successively, starting from top and then descending in ever increasing numbers.

The vimanas are decorated with these aediculae. A hara is a chain of the aediculae comprising kuta, shala and panjara and their staggering. Starting from one end a vimana tala may have a kuta at the corner, a shala in the center and a kuta at the other corner. This scheme would be called a k-s-k scheme. If a panjara is added at the center of the shala then the scheme would be: k-s-p-s-k.

But most of the Hoysala temples are more complex than this and the central shala is staggered and its center is occupied by a panjara which nestles the image of a deity or a celestial figure. The staggered shala would add more shala elements. If it is staggered once then the scheme would be k-s-s-p-s-s-k and so on.

This is the terminology in which the hara decoration of the parapet and vimana of a Hoysala temple are described. In light of this, it would be easy to understand the description of the vimana of the oldest shrine housing Veera Narayana, by Gerard Foekema, in following words:

“The square vimana shows k-sspss-k in three talas and is crowned with giant vedika and kuta roof; the latter, in turn, is crowned by a kalasa. The sukanasi exhibits –p- in the first tala and –k-spsk in the second. The closed hall shows k-sp-sssspssss-ps-k. The open hall shows k and sps as a hara of pavilions only.”

There is an eave running round it. Above the eave, the vimana is profusely decorated and below it the walls are plain. There are two explanations of it. 1. That the vimana was decorated later, when the other two shrines were created. 2. That it was done purposefully to show that the garbha-griha is a place for meditation, even from the outside and hence does not reflex the complexity of the world.

The two lateral shrines are completely decorated from top to bottom, except the moulding of the base. The vimanas are profusely decorated, and so are the wall sections below the second eave. These two vimanas were built in the later Hoysala period and hence they have two eaves, one directly below the parapet and second a little below it. Between the two eaves are stambha frames of different kinds. Both the shrines have antarala and shukanasika.

These two vimanas are different in a crucial way. The southern shrine of Venu-Gopala facing north has a Dravida vimana. It is 4.9 metre of height. It is a triratha square with k-sspss-k articulation. The northern shrine of Yoga-Narasimha facing south has a Vesara vimana. It is a triratha half star with k-.-ksspssk-.-k articulation on its vimanas. Its height is 4.7 metre.

While the shukansika of the southern shrine is square with k-sps-k articulation in its second tala, the shukanasika of the northern shrine is more complex as its plan is of a full star. The center of both the vimanas are decorated with the panjara aedicule and an additional decorative panjara is added in the vedika and vyalamala section, interrupting them, but consequently giving the impression of a vertical band of panjara aedicule in the forum of kirtimukha.

Most awe-inspiring are the lathe-turned pillars which are 108 in number. There is still no clue how these pillars were created. But they give a marvellous look and support the roof very well. No two pillars are alike. They are all different. There are elephants present inside the temple too, which also support the elephant outside in carrying the ratha forward. These elephants are relocated by the ASI which renovated the temple in 1960s. Between the two shrines is the defining member of the Belavadi temple: the largest combined mahamandapam of any Hoysala temple. It has 59 bays. Its plan is that of a staggered square and diagonally it gives the impression of a star. A huge eave, measuring one metre across runs around the mandapa. From the inside it has the imitiation of a wooden rafter, like many other Hoysala and Chalukya temples. The hara above this eave is decorated, as is the kapota.

The Outer Gate

The outermost gate of the temple is uncharacteristic of the Hoysala architecture and actually resembles the slanting roof structure of the Tulu Nadu region, in coastal Karnataka and Kerala. As one enters this gate and arrives upon the entrance of the actual temple one is greeted by the vimanas of the two lateral shrines described above.

The entrance of the maha mandapam is flanked by two elephants. The priest claims that the elephants are actually forms of Airavata, the divine vehicle of Indra, as they have split-end horns. The Airavata is taking the ratha forward. There are seven doors corresponding to the seven chakras. A devotee who passes through all these doors is supposed to be symbolically penetrating the seven chakras and approaching the brahma-randhra in the garbha-griha where the deity is and which is supposed to give us moksha (liberation).

Garuda Stambha

The temple proper starts from Garuda Stambha, which is inside the outer gate. Shastanga Namaskar is done outside this Stambha. The head priest tells that if the Shastanga Namaskar is done inside this Stambha then it is incomplete as all the gods will not receive it, since Garuda is left behind. Done from outside this place it will go to all including – ashtadikpalas, dvarapalakas, garuda and the main deity itself.

Interior

The interior of the temple is equally exquisite. The ceilings are decorated with various motifs, the most common of them being an upside lotus hanging from the ceiling. In the bhuvaneshwari or closed mandapa, Dashavatar of Vishnu are also depicted, along with the ashtadikapalas. It also has the ashtadikpalas, the guardian deities of all directions. The main sculptures inside the sabha mandapam, or the smaller open mandapam are:

- Ashtadikpalas

- Hoysala motif – Hoysala King killing lion

- Samudra Manthan

The rest of the temple too depicts many beautiful sculptures. Some important ones are described below:

- Kodanda Rama

- Adi Devatas

- Dashavatar

- Chaturvimshati Vishnu

- Kaliya Mardana

- Govardhan

- Chamara Sakhi

- Dvarapalakas

- Yali – elephant, lion, pig, peacock

- Hamsa

- Floral Motifs

- Anjaneya

- Garuda

- Bhoga Narasimha (standing)

- Dhyana Mudra Krishna

- Natya Vishnu

- Darpan Sundari – Madanikas

- Hamsa

The administration and management

The temple is run by three different institutions. One is the Archaeological Survey of India, which takes care of the lawns and the gardens of the temple. A man is appointed by the government organization as it is a heritage temple and the cleaning of the outside premises, the fencing and the lawns are maintained appointed by the ASI. The head priest says that the ASI team is not concerned with the spiritual aspect of the temple. It is only concerned with the aesthetics and architecture and takes care that the temple should look good and clean.

ASI’s apathy of the spiritual and ritual aspect of the temple has reduced many great temples to just archaeological ruins. Sometimes, spiritually and functionally important parts of the temples are not renovated as they are not considered important enough from the point of view of aesthetics. The temple tank of Belavadi tank was a casualty of this. It had gone to ruins even before the ASI took over, but when the ASI renovated the temple in the 1960s, it was decided that the temple tank was not important to renovate and hence it was left in ruins and then filled over.

The second institution which maintains the temple is the family of the hereditary priest and the larger Vaikhanasa community. The current chief priest is Prashant S. Bhardwaj, whose family has been in charge of the temple for at least as long as four hundred years.

The third institution which takes care of the temple is the Sringeri Sharada Peetham, one of the four Mathas established by Adi Shankaracharya. The Sringeri Peeth is located in the Chikamagalur district in which the village of Belavadi lies. It is 114 km from Belavadi. It is the Sringeri Matha which runs the temple in the sense that it takes care of the rituals and festivals that go on in the temple. It is the Sringeri Matha which employs the head priest and takes care of his family as well as taking care of other needs of the temple.

An employee of Sringeri Peetha lives in Belavadi who takes care of the needs of the temple – mainly about all the worship that is offered and the naivedyam that is offered. Sringeri Peetha provides a basic salary to the temple priest, which is now at 2000/- for Belavadi Veera Narayan temple. The temple priest cannot hold any other job and cannot accept any other salary other than the donation by the devotees.

It is notable that though Sringeri Matha is a basically a Shaiva (Smarta) Matha, but it takes care of the Vaishnava temples too without any discrimination. The exaggerated stories about the differences between Shaivas and Vaishnavas in India have been the handiwork of the Marxist historians with vested interests. A cursory look at the affairs of how Mathas and temples are run clears the doubts.

After the Hoysala Empire, this temple came under the care of the Vijayanagar kings and after their fall in the 16th and 17th centuries, it remained autonomous for some time, but in 18th century the Wodeyars of Mysore gained control of it and started taking care of it. And in 1760, for better care they donated the temple to the Sringeri Sharada Peetham. No matter who controlled the temple, as long as it remained under the Hindu lordship, the rituals and worship continued in the temple as ever before. In 18th century, as until very recently, the village of Belavadi was very rich, as its water table was very high and it was rich in resources and manpower. It was quite capable of taking care of itself and the grand temple at the center of the village, but the over lordship of Sringeri Peetham made sure that proper rituals according to the Vaikhanasa Agama always continued there.

The Case of the Mujarahi Temples

The head priest says that most of the temples in Karnataka are Mujarahi temples which come under the government rule of the state government. They are just allotted three thousand rupees every month. And they are in apathy. The government takes every bit of rupee that devotees give to the temple but do not allocate enough funds so that the temples can be run well.

The Belavadi temple does not have to give its donation to the government as it is not a mujarahi temple. The Sringeri Matha also does not collect donation from temples like Belavadi which are not cash rich. They understand that temples need funds for running themselves and thus Belavadi temple is free to run on its own.

The Shankara Matha Sringeri preserves many such temples across India and Karnataka and runs many Sanskrit schools and any such heritage institutions all over India.

In ancient times, kings donated lands for the management and monthly expenditure of the temple. That is why the temple had land aside from what the building occupied. During the period of Indira Gandhi government, a law was formulated which dictated that whoever resides on a given land owns it and hence the tenants became landowners.

Thus in one swift action, the temples lost their sustenance along with the temple priests. As a result, the temple priests also lost their lands and fled to other places abandoning the temples as they could no longer be maintained. In one cruel action against Hindu culture and civilization the Indira Gandhi government killed the living Hindu temples, temples which had weathered the Islamic attacks as well as the advances of Christian missionaries. One wonders how such unthinking and cruel action can take place in modern India but the Congress government has taken many such steps.

In traditional Agama set-up a priest was completely devoted to the worship of the temple deity and hence he did not have any time for farming and growing his own food. He was a specialist in a society which valued its spiritual needs as much as its physical needs. Those who were landless were given land to farm which originally belonged to the family of the priest. They took half of the produce themselves and gave half of it to the priest so that he could eke a livelihood. It was a win-win situation for both the priest and the farmer who did not have any land but was benefitting from the temple land. It was a wonderful system which was destroyed by the Indira Gandhi government.

The Vaikhanasa community and the Vaikhanasa agama

The Vaikhanasa Agama is one of the most ancient and most primary Agamas which are in practice in Hindu temples in India. The Vaikhanasa Agama is particularly prevalent in south India and the Vaikhanasa community is found in the states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. The most famous temple that uses the Vaikhanasa Agama in the temple rituals is the Venkateswara temple at Tirupati. S. K. Ramachandra Rao affirms the ancient origins of the community: “The members of the community belong to the Taittiriya division of Krsna-Yajurveda among the Brahmins, and have retained common customs and traditions, although spread widely in the three states mentioned above. They are endogamous and closely knit. It is undoubtedly an ancient community, heavily ritualistic in orientation and entirely Vedic in affiliation.”[9]

The Vaikhanasas are the worshippers of Vishnu and in this way they are Vaishnavas, though they differentiate themselves from the other Vaishnava communities following the Panchratra Agama, because the Vaikhanasas still carry on the Vedic rituals, recite Vedic mantras and perform Yajna.

They conduct fire rituals just like it is prescribed in the Vedas, in the temples, quite unlike other Panchratra Vaishnava temples in the south. “The Vaikhanasas carry on their worship entirely with Vedic mantras…”[10]

The Vaikhansas believe that bhakti (devotion) alone is not enough and that in this age proper icon worship is necessary to attain self-realization. S. K. Ramachandra Rao believes that it is possible that the focus of the Vaikhanasas on the icon-worship maybe the catalyst that gave birth to the Vaishnava movement led by Ramanujacharya in the south. Evolving from the Vedic era, the Vaikhansas have adopted icon worship at home and the temples, having recognized the need for a permanent structure for conducting the divine rituals, but they have equally carried on their respect for the Vedas and have incorporated the Vedas in the rituals of temple worship. They recognize the authority of the Vedas so much so that they do not even call their texts or tradition as Agama, but call their scripture as simply ‘Bhagavaca-Shastra’.

The Vaikhanasa community is perhaps the oldest community to cultivate icon worshipping in the temples. The Vaikhanasa scripture is said to be the oldest Agama, as it directly evolved from the Vedas. The Vaikhanasas as a community are at least as old as the age of The Mahabharata and The Ramayana as they are mentioned in both. Hence they are at least five thousand years old. At first they must have been worshipping icons in the forests and gradually as the temple worship evolved great temples were built in which they continued the fire rituals of the Vedas along with many other rituals needed for the temple worship.

“The religious scene was shifted from the sacrificial enclosure to the temple precincts; but the Vedic mantras continued to be employed. The priests continued to perform the Vedic rites in their own homes as they were done in the olden days; and the Vedic rites were incorporated in the worship sequences in the temple. The purpose of the Vedic rites was essentially to obviate the sins acquired by ignorance, and to bestow peace and tranquility here and hereafter.”[11]

The scripture of the Vaikhanasas is said to have delivered by Lord Vishnu himself to a form of his own called Sage Vikhanas, who is said to have come from Vishnu himself. It is the followers of the Sage Vikhanas who are called Vaikhanasas. This is how the community traces their origin directly to Vishnu.

In Belavadi, only 25 Brahmin families are left now. Only one of those families belongs to the Vaikhanasa community. Prashant belongs to that family. After the death of his father he is now the chief priest. He is from Bharadwaj Gotra. Belavadi has a population of 2500 and has around 800 families. The ASI rule is that inside the 100 m radius of the temple new construction cannot be done.

There are only 10,000 Vaikhanasa families left in India. They are basically from Nemisharanya. These families mostly live in Tamil Nadu and some in Andhra. Very few of them are left in Karnataka. Belavadi family is one of them.

Worships offered in the community

In the Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi, the worship is offered twice a day. In temples which have more resources and more number of priests have up to five times daily worship but the Veera Narayana Temple has only one priest, as the head priest and hence the worship is offered only twice a day: in morning and evening.

In the morning, after offering the worship, naivedyam is offered to the deity and then prasadam is distributed among the devotees who are present. In evening special offering of coconut is made. The morning worship takes place at 10 AM and the evening worship takes place at 5 PM.

The worship that is offered at the Veera Narayana Temple is usually called Shodasha Upachara Puja. It is offered in many communities and temples across India. As the phrase suggests, this worship contains sixteen elaborate steps. Only when all the steps are completed in the right order that the worship is considered to be properly offered. The sixteen steps are:

- Dhyanam (Meditation) – A short prayer is offered and the priest meditates on the lotus feet of the god.

- Aavahana (Invocation) – The priest invokes the particular deity that he is worshipping, inviting him to come inhabit the image in the place of worship.

- Aasana (Offering Seat) – The deity is invited to come and sit down comfortably.

- Paadya (Washing of Feet) – The feet of the deity are washed along with the recitation of the mantras.

- Arghya (Washing of hands) – The deity is offered with water for the washing of hands. The act is done by the priest with ritual incantation.

- Aachamana (Offering water to drink) – The deity is offered water for drinking along with the recitation of proper mantras.

- Snana (Bathing with water or Panchamruthas) – The deity is ritually bathed with either water or with Panchamrutha on special occasions and festivals. Alternatively the deity is bathed with milk, yoghurt, ghee, honey, sugar, coconut water, fruit juice, sandal powder, turmeric one at a time.

- Vastra Abharana (New Clothes) – After bathing, new or freshly washed clothes are offered to the deity.

- Yajnopavita (Offering of sacred thread) – The deity is offered fresh Yajnopavita, made by the priest at his home.

- Gandha (Sandal paste) – The deity is applied with sandal paste. It is put on the forehead.

- Archana (Offering of flowers) – Freshly picked flowers from the temple garden are then offered to the deity.

- Dhoopam (Incense) – Incense is lighted to create divine atmosphere in front of the deity in the garbha-griha. It is believed that as the smoke of dhoop reaches the deity, so the soul aspires and reaches self-realization.

- Deepam (Oil Lamp) – Then the oil lamp is lighted. The garbha-griha of the Hindu temple is often dark and the lighting of the lamp is thus an integral part of the Shodash worship.

- Naivedyam (Offering of specially prepared food) – Food prepared cleanly by either the mother or wife of the priest, or the special cook that is appointed by the temple is offered to the deity. After the deity has tasted the food it becomes prasadam which is then offered to the devotees.

- Tamboolam (Offering of Betel Leaves and Betel nuts) – The deity is offered with betel leaves and betel nuts after he has taken the naivedyam.

- Neerajanam – Aarati of the deity is performed with a camphor lamp. The deity has arrived and is satiated.

This worship is offered twice every day in all three shrines of the Veera Narayana temple: to Veera Narayan, to Narasimha and to Venugopala. Apart from this many special worships are offered to the deities many times around the year. Once a month, special worship is offered to all three deities:

- Narasimha is offered special worship every month on Swati Nakshatra

- Veera Narayan is offered special worship every month on Shravan Nakshatra

- Krishna is offered special worship every month on Rohini Nakshatra

Festivals

Abhishekam – Along with elaborate worship, abhishekam is offered to the deities on the day of their special worship, at least once a month. There are other festivals, birthdays and yearly festivals which are celebrated. Abhishekam is offered on every one of these occasions. Apart from that if the devotees want to offer abhishekam they donate the ingredients to be used in it or donate the money allocated for it to the temple and the head priest offers the abhishekam to the deity on the behalf of the devotee. The monthly abhishekam is also called pakshotsavam.

Kumbhabhishekam – While abhishekam of all three deities is done at least once every month and many other times during the year, during various yearly festivals, every twelve years an abhishekam bigger than all others is offered. It is called Kumbhabhishekam. It is a huge form of abhishekam. Just like the Kumbh Mela it comes every 12 years. It is a sort of re-consecration of the murti, the temple deity. All the mistakes in worship that is done in the preceding 12 years are said to be eliminated in this re-consecration which purifies the image and makes it fit for the dwelling of the deity.

Like all great Hindu temples, the Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi also celebrates many festivals round the year. The four biggest festivals which are celebrated in the Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi are:

- Krishna Janmashtami – As it is a Vaishnava temple and one of the shrines houses the image of Venugopala, the form of Krishna playing flute, the festival of Krishna Janmashtami is celebrated with great gusto in the month of Bhadrapada, generally falling in the month of August.

- Narasimha Jayanti – It is celebrated on the fourteenth day in the bright fortnight of the Vaishakha month (Vaishakha Shukla Chaturdasi).

- Rath Yatra – It is the great festival of the temple, celebrated on the Chaitra Purnima which falls six days after Ram Navmi. It is a huge festival of Veera Narayana Belavadi temple.

- Rath Saptami – This festival falls in the Bhadrapada month during August or September and is a big festival.

- Nityagnihotram – The priest says that in Belavdi in the ancient times there were around 300 Brahmin families in the village. They performed Yajna twice every day. This is called Nityagnihotram. But during the Muslim invasions this tradition frittered away due to the lack of patrons whose livelihoods were destroyed by the Islamic invasions. The priest testifies to the destruction of the Hindu heritage by the Islamic invasions.

- Other seasonal festivals that are celebrated at the Veera Narayana temple are Shravan Puja and Kartik Utsava.

Details of rules and regulations

The Vaikhanasa Agama like all other Agamas proscribes certain actions that are to be done and certain actions that are prohibited. All of these instructions are followed in the Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi. These instructions are as follows:

Vaikhanasa Agama – Rules and Regulations

- Entering a shrine or moving about in its precincts in a vehicle or with footwear is improper.

- Before entering the temple, the devotee must go round it in the customary circumambulation (pradakshina), keeping the shrine to the right), and this must be done with deliberation, and not in a hurry.

- The temple is a form of the Godhead; and its towers must never be trodden with feet.

- Before going round the shrine in customary circumambulation, one must prostrate or bow before the shrine.

- Only while going round in circumambulation, one may step on the shadow of the entrance tower (gopuram), superstructure over the sanctum (vimana), enclosing wall (prakara), or the banner-post in front of the shrine (dhvaja), and never otherwise.

- While entering the shrine, one must not wear his sacred cord the wrong way viz. hanging by the right shoulder, apasavya or hanging by the neck like a garland (nivita), or wound round the ear. He must wear his lower garment (dhoti) well tucked up (kachha), and the ends of the cloth must not hang behind him like a tail (puccha). He must never enter the shrine naked or wearing only a piece of loin-cloth covering his genitals (kaupina).

- He must, while entering the temple, also wear an upper cloth (uttariya) neatly and pleasantly. He should not cover his body with stitched garments (viz. shirt, coat etc.) or with blankets. Nor should he wear a headgear (viz. cap, hat, turban etc.). He should not carry any weapon in his hands.

- One must not enter a temple empty-handed: he must carry some offering to the deity (viz. coconut, plantains, flowers etc.) He must not be eating food brought from outside or chewing betel-leaves while going into the temple or while he is within the temple-premises. His forehead must not be blank (viz. he must wear a mark in accordance with his religious affiliation,)

- If he eats in the temple the food given to him as Prasada (already dedicated to the deity), and throws away what remains over in the premises of the temple, it is improper and thoughtless.

- A person in physical or mental distress should not enter the temple. If he has disorders of the vital currents, he should take care to see that he does not evacuate his bowels or expel flatulence, while in the temple. One who is sick must not enter a temple.

- One whose mind is confused, agitated or not at rest cannot worship the Deity in the temple. Indeed, it is only one whose mind is pure and steady that is fit to perform any religious act.

- No one should stretch his legs across or sleep at the doorstep of the temple; nor should he be inebriated near or inside the temple. One must always be alert, awake; humble and erect while within the temple-premises.

- It is not proper for anyone to go to the temple or be in its precincts crying in anguish or weep in devotion. If prayers are offered out of grief, it is a blemish of the mind. The person who feels distressed within the premises of the temple does not know the nature of God’s presence or the purpose of his visit.

- The heart that is free from passions, the speech that avoids lying, harshness, slander and deceit, and the body that abstains from causing violence of any kind are necessary for worship in a temple.

- Having entered a temple, one should never commit an act of violence, which may cause suffering to any living being. Non-violence, virtuous conduct, meditation, control of the senses, penance and service to the elders are considered the six gateways to Dharma.

- The person who gossips in a temple, and chatters without restraint does a wrong thing. One should not talk needlessly. There are other places in plenty where on may discuss worldly matters; and there are other times for it. Why should one indulge in such talk in a temple? Having entered a shrine, he should think of god, and meditate at least for a moment, if not for some hours. If he does not do so, he would waste a great opportunity. He would be like one who is deluded or pervert. Which wise man will abandon the food that is prepared and ready, and begs about for a few crumbs? Who will ignore the treasure at hand, and go about begging? Wheel in a temple, the devotee should not think of anything else.

- Standing in God’s presence in the temple, one must never utter a lie. God is of nature of truth, and truth must not be sought to be hidden from God.

- The temple is no place for discussions on scriptural issues. Engaging oneself in such activities, one would only insult and offend the Deity. Reading, writing and similar preoccupations are equally improper in a temple. Nor should one image in unrestrained an argumentative talk.

- One should not quarrel in a temple or any account; the temple is not the place for it.

- Having gone to a temple, one should not eulogize himself or be arrogant. Disregarding the elders or the Deity, should one talk without restraint about himself, it is a sin which he may not be aware of.

- Talking to another person in a contemptuous manner within the temple premises is not correct. The wise ones will not make a distinction between slighting others and killing them. One should avoid talking ill of others in front of God; nor should one praise another person either, in a temple, for any reason. God is the highest and most supreme reality, and who can be higher than God or more praise-worthy? A mere human being should not be praised or honoured within a shrine. Doing so will not make for happiness.

- One should not greet or bow before another person while in a temple; God is the lord of all, and we are all subordinate to Him.

- Having gone to a temple, one should never sit with his back to the Deity. The devotee should be facing God all the time, and when circumambulating, one should move keeping the Deity to his right.

- There are sequences of worship in a temple, when the Deity in the sanctum is screened off; tradition does not allow the Deity to be exposed to public view on such occasions. No one should desire to see the Deity during these periods. Should one force his way, because of his office or power, he will come to grief. Likewise, when the doors of the shrine are closed after the last sequence in worship, no one, however influential, should ask for the doors to be opened for him. One should have the humility to visit the shrine only after the doors are opened at the appointed time in the morning. Devotees must have the darshan of the Deity only when sequences of worship allow it.

- A person with evil conduct will never prosper; living beings are afraid of him, and offend him. It is only a virtuous person who should undertake the activities prescribed in the scriptures (like going to a temple).

- If the human beings, who are distracted by worldly cares, do not engage themselves in worship of the Deity, their life on earth is wasted, even as all that they do would be in vain. One who regards his preceptor as a mere human being, the Deity as only a stone image, the Vedic mantras as a just a means of livelihood, the sacrifices as violence, and one who is indifferent to the priest or to the worship rituals becomes blameworthy; and his life would be of no value.

There are certain actions that are prohibited by every Agama, including the Vaikhanasa Agama, for maintaining the ritual purity. The following twenty-two acts are regarded as offensive in the Veera Narayana Temple as ordained in the Vaikhanasa Agama:

- Moving bout in a temple on a vehicle or with footwear.

- Not attending to a ceremonial function that is going on (like procession of deities), and not showing reverence to the Deity.

- Making obeisance with one hand only (viz. not joining the palms) and going round in circumambulation in front of the Deity.

- Prostrating etc. before the Deity when one is unclean and polluted.

- Stretching of legs in front of the Deity, or sitting on a seat (or cot) with ones legs dangling.

- Sleeping or lying down.

- Eating food.

- Gossip with people.

- Loud talk, useless chatter, crying and quarrel.

- Punishment and bestowal of favour.

- Confidential talk with women, and obscene remarks.

- Elimination of flatulence.

- Covering oneself with blankets.

- Condemnation or praise of others.

- Honouring a powerful or influential person.

- Eating what is not given as ‘prasada’.

- Not presenting to the Deity fruits and flowers that are seasonal.

- Giving away what remains over (after offering to the Deity) for use in the kitchen, or for others in the temple.

- Sitting or standing with one’s back to the Deity.

- Greeting others and not recognizing an elder (or preceptor) who is nearby.

- Praising oneself.

- Being critical of the Deity.

These are considered as preventive measures for a devotee, however if he commits any of the above forbidden acts then he should quietly ask for forgiveness from the Deity and the effects of his wrongdoing will be counteracted.

The Veera Narayana Temple, Belavadi maintains ritual purity as ordained in the Vaikhanasa Agama and no one except the head priest enters the garbha-griha. Unlike some modern temples where the devotees go and touch the image of the deity in the garbha-griha itself, the Belavadi temple still follows what the scriptures prescribe.

The head priest says that his family is particularly very strict about maintaining purity about the temple and temple worship. The temple priest is not allowed to eat or have anything cooked outside his own home and the day when he has to eat anything outside he does not offer worship at the temple that day. A relative is instructed to offer worship when the chief priest is travelling.

The priest says that the worship is always offered on an empty stomach. Nothing is ever eaten inside the temple. Before starting worship the priest should have his mind, body and soul in line for meditating upon the deity.

The priest cannot touch anyone before offering worship. The dog cannot come in nor can be touched. The cow can be touched. The crow cannot be touched or the priest has to take bath again. Women cannot be touched by the priest either, after the bath has been taken and or in between the worship.

Only freshly washed clothes have to be worn. Neither can be they touched by anyone once they are washed. Only the priest can touch them. Some priests enter the temple after bathing in only wet clothes. Devotees cannot eat, play or sleep within the temple.

The priest wears white in general. During Deeksha (initiation ceremony) they wear Deeksha Vastra – yellow in colour. Yellow is generally preferred in the south, especially in Belavadi temple. Sometimes a kankana is worn when a sankalpa is taken and then only yellow is worn. Saffron is worn only by the brahmachari and white only by the grihastha. However, saffron is worn by the married ones when abhishekam is done.

When a family member dies, the priest cannot enter the temple for ten days. He enters it only after shuddhi. A relative offers worship in the meanwhile.

That is why in ancient times, when the Hindu temple had a central place in the Indian society, two or three families were employed for worship in one temple so that if one family or two families have some deceased in their home then worship would not have to be stopped as there will always will be someone to offer worship.

These three families were from different Gotras as people of one Gotra are considered family. While a child is born, then too, worship is not offered by the priest. A relative has to offer worship, as a certain period after the child birth is also considered to have made the priest incapable of worshipping for reasons of ritual impurity.

Prayashchittas (Penances)

The Hindu temple functions as place where people come for atoning their sins, or for omitting a bad karma in their kundali. Veera Narayana temple and especially the shrine of Narasimha is a place where many people come to omit the faults in their Kundalis. Kuja Dosha is a defect in the kundali. People come to the temple to offer worship and remove these doshas.

Other temple traditions

Temple Ornaments

Usually temples have traditional families from which they buy gold. But Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi, has ornaments which the temple has inherited from centuries. They are kept at the house of the head priest. In bigger temples, clothes of the deity are changed every day and one cloth is not worn again, but in Belavadi, the clothes are worn again by the deity though they are washed every day. In many other temples where there are too many clothes which the temple receives in donation, the clothes are changed daily and the worn clothes are auctioned off to the devotees who wear it as prasadam. In some temples they are sold off at a fixed low price.

Recitation of the Vedas

Belavadi invites Vedpathi Brahmins (Brahmins expert in the recitation of the Vedas) every year to recite the Vedas and generally devotees and the priests also do it from time to time. In bigger temples, such Brahmins are permanently kept in service for this purpose. As the Veera Narayana temple, Belavadi follows the Vaikhanasa Agama for following worship rituals the recitation of the Vedas is an integral part of its routine.

Temple Kitchen

Food for the deity is generally cooked in the temple in a Pak Shala (temple kitchen), and if this is not possible then it is cooked by the head priest at his home or someone from his family. In Belavadi it is cooked in the home of the head priest. Nothing cooked outside is offered to the diety. This rule is strictly followed.

Flowers

The Vaikhanasa Agama dictates that all the flowers that the temple needs should be grown in the garden maintained by the temple, but as the Veera Narayana temple is a monument of national importance and is looked over by the ASI, the flower garden is maintained for pleasure and not for the purpose of the temple. The temple buys all the flowers that it needs. The Sringeri Matha has appointed a man who looks after these needs of the temple. It is he who buys the flowers for the temple.

Temple Musician

Until a few years ago, there were temple musicians who lived in the village of Belavadi whose sole function was to play instruments for the temple at special occasions. He was given land by the temple to earn his livelihood. This is no longer so. The musicians are invited on special occasions.

Temple Elephant

An elephant is an integral part of a large Hindu temple. The temples of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have become synonymous with elephants as they are still functional institutions and are still at the centre of the social life. They are not short of donations or money and hence it is easy for them to maintain one or more than one elephants. This used to be the tradition at almost all big temples in India, but the Islamic invasions destroyed this tradition along with many others. The temple at Belavadi used to have an elephant until a few decades ago but now it does not have a temple as the expenses are too much and the temple cannot meet those expenses. The Vaikhanasa Agama describes the deities as seated on the elephants and horses and hence these animals have special significance. That is why such animals had special significance in the Hindu iconography and as the temple is an expression of Hindu iconography and so elephants along with other animals were a sacred part of the temple. During festivals Utsav Murti are placed on the elephants and taken on procession. Elephant is the royal vehicle.

Temple Cows

The temple also kept its own cows but now it does not anymore. The head priest says that when the temple ran with old structure and the temple owned lands devotees in different capacities dwelled on those lands and served to the temple in different capacities. The whole town was connected with the temple and the temple was the epicenter of the lives of the villagers. But now this is no more. The old system is crumbling down under the harsh treatment of governments which are at best unsympathetic to the interests of the Hindu temple.

Earlier there used to be an Agrahara in front of the temple where Brahmins and students learning the Hindu shastras dwelled. But now this tradition is also gone as the sustenance that the temple received from kings is gone and so all who depended upon temples have now to look elsewhere for earning their livelihood.